THE UK MEDIA LAW POCKETBOOK

by Tim Crook

Second Edition Published by Routledge 30th November 2022

Second Edition Published by Routledge 30th November 2022

If you are reading and accessing this publication as an e-book such as on the VitalSource platform, please be advised that it is Routledge policy for clickthrough to reach the home page only. However, copying and pasting the url into the address bar of a separate page on your browser usually reaches the full YouTube, Soundcloud and online links.

The companion website pages will contain all of the printed and e-book’s links with accurate click-through and copy and paste properties. Best endeavours will be made to audit, correct and update the links every six months.

Chapter 2

Guide to Court Reporting – Key facts and check-list

A special guide to applying primary and secondary media law to the process of court reporting.

The important of attribution, facts not comment, appropriate dress and conduct, background research and preparing technology and reconnaissance.

Negotiating access and rights of access to court case documents and multi-media materials used in evidence.

The importance of respecting restrictions relating to children and sex offence complainants, appreciating identity of protagonists, their titles and jargon and terminology, trial and case structure and narrative, practice in using cameras, recording and tweeting devices.

Applying the duty in accuracy, fairness, and the technique of note-taking for immediate reporting.

Absence of jury rule, taboos in interviewing jurors and judges, press conferences after a case has ended and the need to keep notes and records.

Video-cast Guide to Covering Court Cases

2.0 Key rules and professional standards when court reporting in bullet points

A downloadable sound file of bullet point professional tips and rules for court reporting

2.1 Attribution, facts not comment etc

A downloadable sound file on this section emphasizing attribution and avoiding comment

2.2 Respectfully dressed and respectfully behaved

A downloadable sound file stressing the need for respectful presentation and behaviour

Online Links Printed Book

Page 72

IPSO Court reporting: What to expect. Information for the public.

https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/1511/court-reporting-public.pdf

Combatting Online Harassment and Abuse: A Legal Guide for Journalists in England and Wales

https://medialawyersassociation.files.wordpress.com/2021/06/combatting-online-harassment-and-abuse-23.06.2021-09.10-5.pdf

Kate Cronin for Northamptonshire Telegraph: ‘Why is it important for Northants Telegraph journalists to cover inquests?’

https://www.northantstelegraph.co.uk/news/people/why-is-it-important-for-northants-telegraph-journalists-to-cover-inquests-3278300

2.3 Information preparation: Check your technology and reconnaissance

A downloadable sound file on how to get ready for your visit to court

2.4 Availability of agreed prosecution opening, skeleton arguments etc

Online Links Printed Book

Page 77

Guardian News and Media Ltd, R (on the application of) v City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court [2012] EWCA Civ 420 (03 April 2012)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2012/420.html

Criminal Procedure Rules and Practice Directions 2015 updated and consolidated for 2022

https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/CrimPD-12-CONSOLIDATED-March-2022.pdf

Protocol for working together: Chief Police Officers, Chief Crown Prosecutors and the Media

https://www.cps.gov.uk/publication/publicity-and-criminal-justice-system

Example of materials released for media use in the trial of former Metropolitan Police Constable, Wayne Couzens, sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of Sarah Everard in September 2021.

https://twitter.com/cpsuk/status/1443537576523182080?lang=en-GB

The Guardian leads legal battle to show CCTV footage of Thomas Orchard being restrained and an emergency response belt placed over his face

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/feb/24/footage-of-thomas-orchard-died-restraint-with-webbing-belt-revealed

2.5 Reporting restrictions – children, sex offence complainants

A downloadable sound file summarizing your need to check reporting restrictions

2.6 Names of protagonists, their titles and proper terminology etc

A downloadable sound file on reporting names and titles when covering criminal trials

Online Links Printed Book

Page 79

England and Wales Courts and Tribunals guide to ‘What do I call a Judge?’

https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/what-do-i-call-judge/

The Justice System in England and Wales

https://www.judiciary.uk/about-the-judiciary/the-justice-system/

Structure of the courts and tribunal system in England and Wales

https://www.judiciary.uk/about-the-judiciary/the-justice-system/court-structure/

2.7 Understanding the trial/case structure and narrative

A downloadable sound file on understanding how a criminal trial proceeds

Online Links Printed Book

Page 81

Going to court guide for England and Wales

https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/

Court of Appeal: https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/court-of-appeal-home/

High Court: https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/high-court/

Crown Court: https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/crown-court/

Magistrates’ Court: https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/magistrates-court/

County Court: https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/county-court/

Family Court: https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/family-law-courts/

Tribunals: https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/tribunals/

Coroners’ Court: https://www.judiciary.uk/about-the-judiciary/the-justice-system/coroners/

2.8 Cameras, recording and tweeting

Online Links Printed Book

Page 82

Ministry of Justice discussion paper on ‘Proposals to allow the broadcasting, filming and recording of selected court proceedings’ May 2012

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/217307/broadcasting-filming-recording-courts.pdf

2.9 Accuracy paramount

A downloadable sound file on how to maintain accuracy when reporting court cases

2.10 Fairness paramount

A downloadable sound recording on how to maintain fairness when court reporting

2.11 Use notes/scripts for live broadcasts

A downloadable sound file on best practice when ‘live reporting’ from court cases

2.12 In the absence of the jury usually report nothing

2.13 Interviews – judges and jurors no, others be careful where and how

2.14 Qualified privilege at press conferences – useful

2.15 Keep your notes and case papers

A downloadable sound file advising on the keeping of notes and records

Online Links Printed Book

Page 87

Under the Data Protection (Charges and Information) Regulations 2018, individuals and organisations that process personal data need to pay a data protection fee to the ICO, unless they are exempt.

Registration self-assessment: https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/data-protection-fee/self-assessment/

2.16 Dealing with stress-related issues when covering disturbing and shocking court cases

Online Links Printed Book

Page 88

Hold the Front Page ‘Reporter urges support for colleagues covering “traumatizing” trials from home’

https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2020/news/reporter-urges-support-for-colleagues-covering-traumatising-trials-from-home/

The Conversation: ‘Media companies on notice over traumatised journalists after landmark court decision.’

https://theconversation.com/media-companies-on-notice-over-traumatised-journalists-after-landmark-court-decision-112766

The Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, a project of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, is dedicated to informed, innovative and ethical news reporting on violence, conflict and tragedy.

https://dartcenter.org/europe

2.17 Access to the courts for student journalists

Online Links Printed Book

Page 89

Ewing v Crown Court Sitting at Cardiff & Newport & Ors [2016] EWHC 183 (Admin) (08 February 2016)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2016/183.html

HMCTS: General guidance to staff on supporting media access to courts and tribunals

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1094686/HMCTS314_HMCTS_media_guidance_June_2022_v2.pdf

2.18 More information on court reporting resources, stop press and updates

Online Links Printed Book

Pages 92 to 94

HMCTS Reporters’ Charter, May 2022

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1074233/HMCTS702_Reporters_Charter_A4P_v4.pdf

HMCTS media guidance – managing high profile cases (accessible version)

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-to-staff-on-supporting-media-access-to-courts-and-tribunals/hmcts-media-guidance-managing-high-profile-cases-accessible-version

Jurisdictional guidance to support media access to courts and tribunals: Criminal courts guide (accessible version)

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-to-staff-on-supporting-media-access-to-courts-and-tribunals/jurisdictional-guidance-to-support-media-access-to-courts-and-tribunals-criminal-courts-guide-accessible-version

General guidance to staff on supporting media access to courts and tribunals

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1094686/HMCTS314_HMCTS_media_guidance_June_2022_v2.pdf

Jurisdictional guidance to support media access to courts and tribunals: Civil court guide

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/869797/HMCTS_media_guidance_-Civil_Court_Guide_March_2020.pdf

Jurisdictional guidance to support media access to courts and tribunals: Family courts guide https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1074298/HMCTS707_media_guidance_-_Family_Court_Guide_MAY_2022_V1.pdf

Jurisdictional guidance to support media access to courts and tribunals: Tribunals guide https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1103102/HMCTS751_media_guidance_-_Tribunals_Court_Guide_11_Sept_2022.pdf

UK Supreme Court: https://www.supremecourt.uk/

Watch UK Supreme Court live: https://www.supremecourt.uk/live/court-01.html

UK Supreme Court current cases: https://www.supremecourt.uk/current-cases/index.html

UK Supreme Court archive of decided cases: https://www.supremecourt.uk/decided-cases/index.html

The Court of Appeal (Civil Division) – Live streaming of court hearings

https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/court-of-appeal-home/the-court-of-appeal-civil-division-live-streaming-of-court-hearings/

HMCTS Guidance on broadcasting sentencing hearings by the media and the Crown Court (Recording and Broadcasting) Order 2020

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/broadcasting-crown-court-sentencing

CourtServe – Court & Tribunal Lists: https://www.courtserve.net/

HMCTS telephone and video hearings

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/hmcts-telephone-and-video-hearings-during-coronavirus-outbreak#media-access-to-proceedings

HMCTS Guidance to staff on supporting media access to courts and tribunals

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-to-staff-on-supporting-media-access-to-courts-and-tribunals

Society of Editors ‘Old Bailey allows journalists to cover criminal cases from home in legal first’ March 26 2020

https://www.societyofeditors.org/soe_news/old-bailey-allows-journalists-to-cover-case-in-legal-first/

Making hearing lists more accessible to court and tribunal users

https://insidehmcts.blog.gov.uk/2022/02/01/making-hearing-lists-more-accessible-to-court-and-tribunal-users/

IPSO guidance on court reporting for journalists and editors

https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2168/ipso-court-reporting-guidance.pdf

HTFP Law Column: IPSO releases court reporting guidance

https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2022/news/law-column-ipso-releases-court-reporting-guidance/

New Links post publication of the printed book

Reporting Restrictions in the Criminal Courts – fourth edition update https://www.judiciary.uk/guidance-and-resources/reporting-restrictions-in-the-criminal-courts-4th-edition-update/

Judicial College Reporting Restrictions in the Criminal Courts https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Reporting-Restrictions-in-the-Criminal-Courts-September-2022.pdf

Broadcasting Crown Court sentencing Guidance on broadcasting sentencing hearings by the media and the Crown Court (Recording and Broadcasting) Order 2020. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/broadcasting-crown-court-sentencing

Broadcasting from the Crown Court Inside HMCTS Posted by: Rachael Collins, Posted on: 19 August 2022 https://insidehmcts.blog.gov.uk/2022/08/19/broadcasting-from-the-crown-court/

Broadcasting of sentencing remarks in the Crown Court July 28, 2022 https://www.judiciary.uk/broadcasting-of-sentencing-remarks-in-the-crown-court/

The recorded sentencing remarks hosted by Sky News on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF3HqeLrCkZgARQfyqj1m-g

Sections 198 and 199 Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 allowing the Lord Chancellor to empower the Court to direct the electronic transmission of images or sounds of proceedings of all kinds for the purpose of enabling persons not taking part in the proceedings to watch or listen to them, though onward recording and broadcasting is prohibited.

Transmission and recording of court and tribunal proceedings- https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/32/part/13/crossheading/transmission-and-recording-of-court-and-tribunal-proceedings

Errata and corrections to printed book

At the bottom of page 20, the case history and link for the Appeal Court ruling in the Guardian‘s bid to unseal the will of the late Duke of Edinburgh should have been placed in the box section for online resources in support of this section.

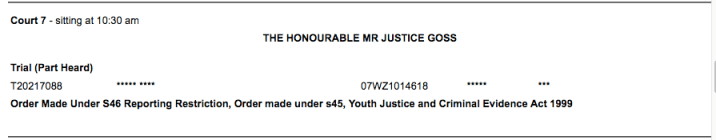

New edition of the Judicial College’s Guide to Reporting Restrictions in the Criminal Courts September/October 2022

On 30th September 2022 after the second edition of UK Media Law Pocketbook went to printing, the Judicial College publicly released its fourth edition of the guide to reporting restrictions in the criminal courts of England and Wales. The last version was updated in May 2016 and a considerable amount of the content needed updating given the passage of six years.

It is downloadable on this embedded link.

Eloise Spensley in the Jaffa Law Column for Hold The Front Page has analysed the new edition with the headline ‘The [court reporting] Times They Are A-Changin.’

Spensley argues the new guide has an ‘apparent focus on welfare and rehabilitation of juvenile offenders, now states that it would be wrong to dispense with a child’s right to anonymity as a form of additional punishment, so-called “naming and shaming.” It goes on to say that the welfare of the child must be given great weight and that rarely will it be the case that it is in the public interest to identify the child.’

Spensley highlights how the guide says: ‘there may be cases where it is necessary to protect the identity of the complainant where no automatic reporting restriction applies. For example, in cases of extortion, or revenge porn perhaps, the Guidance envisages that the proper administration of justice will generally call for the complainant to be granted anonymity to prevent the suffering of further harm.’

Introduction and development of live televising of Crown Court sentencing in England and Wales

Pages 39 to 42 of Chapter 1 of the printed book has a section on broadcasting and online coverage of the courts and following the inauguration of televising sentencing in the Crown Court for the first time at the Old Bailey 28th July 2022, the practice has been gathering what might be described as ‘gradual momentum.’

The head of law at ITV news, John Battle, who is also chair of the UK Media Lawyers’ Association, has been given credit for successfully leading the campaign for this development over many years.

The guidance on who can and how to apply to televise sentencing is set out at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/broadcasting-crown-court-sentencing

Authorised media organisations approved for broadcasting the sentencing are the BBC, ITN, Sky and PA Media.

Any one of them needs to apply to the trial judge 5 days in advance of the sentencing hearing.

No one else can film, broadcast or take photos of any hearing at any time. These ‘authorised media’ can make their footage, including photographic stills from the filming available to other media publishers.

The judge makes a provisional decision at least 2 days before the hearing, and a final decision on the day of the hearing and all this decision making happens outside the courtroom.

The prosecution, defence, victim or his/her relatives cannot make representations and there is no right of appeal against the judge’s decision.

The sentencing judge decides whether sentencing can be broadcast live or not and will take into account any reporting restrictions that are in place.

If reporting restrictions do cover some of the content of a sentencing, ‘there will be a short delay before broadcast to comply with reporting restrictions’ and it is recognised ‘authorised media may need to edit footage before it’s broadcast.’

The copyright in the footage is retained by The Ministry of Justice, but the MOJ is not responsible for maintaining and transmitting the recordings on media platforms such as YouTube.

Key rules that have to be complied with:

1.Only the judge and their sentencing remarks can be filmed. Authorised media cannot film any other court user – including defendants, victims, witnesses, jurors and court staff.

2.Apart from those authorised media organisations identified (BBC, ITN, Sky and PA Media) and approved of by the Lord Chancellor ‘No one else can film, broadcast or take photos of any hearing at any time.’

How HMCTS and the Ministry of Justice explained this historic development for the Crown Court System in England and Wales. ‘Broadcasting from the Crown Court’ See: https://insidehmcts.blog.gov.uk/2022/08/19/broadcasting-from-the-crown-court/

Sky’s hosting platform of Crown Court Sentencing. See: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF3HqeLrCkZgARQfyqj1m-g

Note to student/trainee journalists. Watching these sentencing recordings offers a good opportunity to practice your shorthand or alternative method note-taking in real-time and then to check accuracy and news/journalistic relevance.

You could also set yourself a time deadline of writing up your reports as further practice.

Examples of televised sentencing since July 2022:-

Man jailed for life in first TV court sentencing 28th July 2022 From the number One Court of the Central Criminal Court.

Woman jailed for 34 years for murdering and decapitating friend 28th October 2022 at the Central Criminal Court, London otherwise known as the Old Bailey.

Mother and boyfriend jailed for life over killing of teenage son 7th November 2022 at Leeds Combined Court Centre.

Reservoir Dogs attacker gets further 15 years for murdering partner 22nd November 20222 at Bristol Crown Court.

Necrophiliac killer gets further four years for abusing dead women. 9th December 2022 at the Central Criminal Court, London also known as the Old Bailey.

Judge sentences Anne Sacoolas over Harry Dunn death. 9th December 2022 at the Central Criminal Court, London, also known as the Old Bailey.

Serial offender gets 38 year minimum jail term for brutal murder of Zara Aleena 9 Dec 2022 Central Criminal Court.

Double jeopardy killer gets 25 years for 1975 rape and murder of teenage victim. 13th January 2023 at Huntingdon Law Courts.

Appeal Court- Criminal Division Sentence increased for rickshaw death crash driver. 25th January 2023.

Pair jailed for 35 years for £4.6m murder and fraud plot. 1st February 2023, Central Criminal Court.

Serial rapist and ex-Met officer David Carrick jailed for at least 30 years 14 Feb 2023 Southwark Crown Court.

Son gets life sentence for fatal attack on mother 14 Feb 2023 Central Criminal Court

Embassy spy who sold secrets to Russians jailed for more than 13 years 17 Feb 2023 Central Criminal Court.

Parents jailed for manslaughter after disabled teen’s death, 2nd March 2023 Old Crown Court.

Wayne Couzens gets 19 months for indecent exposure in months before Sarah Everard killing, 6th March 2023 at the Central Criminal Court.

Woman, 22, jailed for eight-and-a-half years for false abuse and grooming gang claims, 14th March 2023, Preston Combined Court Centre.

14-year minimum term for bed mix-up murderer. 1st April 2023 CANOLFAN CYFIAWNDER TROSEDDOL CAERNARFON CRIMINAL JUSTICE CENTRE

Gunman who shot dead Olivia Pratt-Korbel, 9, jailed for at least 42 years. 4 Apr 2023 MANCHESTER CROWN COURT (CROWN SQUARE)

Mum and stepdad jailed over fatal attack on two-year-old daughter. Mr Justice Griffiths at Swansea Crown Court 26th April 2023.

Nigerian politician, wife and medic jailed over organ harvesting plot. Mr Justice Johnson 9th May 2023 at the Central Criminal Court.

Knifeman, 17, detained for murder of ‘defenceless’ 14-year-old. First televisied sentencing of a serious juvenile offender in the adult courts where anonymity reporting restrictions have been lifted. Judge Sarah Munro KC 10th May 2023 at the Central Criminal Court.

Teenagers get life for killing boy, 16, in mistaken identity attack. Judge Sarah Munro KC at the Central Criminal Court again on the same day (10th May 2023) at the Central Criminal Court. A reflection of the terrible toll of knife crime murders taking place in London with young people, often from Black and Asian ethnic communities being the victims.

Double killer gets third life sentence for sexually abusing boy. The Recorder of Nottingham, Judge Nirmal Shant KC at Nottingham Crown Court 11 May 2023. A double killer who brutally murdered two women in the 1990s was handed a third life sentence for violently sexually abusing a young boy in the years before his fatal attacks.

Killer of Nikki Allan, 7, jailed for at least 29 years three decades on. Mrs Justice Lambert at Newcastle Quayside Law Courts 24 May 2023. David Boyd, now 55, was convicted of the 1992 murder of schoolgirl Nikki Allan after advances in DNA technology allowed police to link him to the crime.

Parents jailed for life over murder of 10-month-old Finley Boden. Mrs Justice Tipples at Derby Combined Court Centre 27 May 2023. A couple who murdered their 10-month-old son on Christmas Day 2020 just weeks after he was returned to their care were both jailed for life. Shannon Marsden, 22, and Stephen Boden, 30, burnt and beat Finley Boden, leaving him with 130 separate injuries, including multiple bone breaks and fractures.

Mother and partner jailed for toddler’s violent death. A mother and her partner were jailed over the death of her 15-month-old son, who was shaken and beaten to death. 28 May 2023 Central Criminal Court before Mr Justice Sweeting.

Life sentence for teen terrorist who plotted attack on police and soldiers. The Recorder of London, Judge Mark Lucraft KC at the Central Criminal Court 2nd June 2023. A teenager who admitted he was planning a terror attack on the police and military was jailed for at least six years.

Killer, 15, gets 12-year minimum term for knife murder. 15 Jun 2023 Newcastle Quayside Law Courts before Mr Justice Martin Spencer. A 15-year-old boy was locked up for at least 12 years for stabbing another teenager to death.

Musician jailed for 15 years for killing student in “Mafia stiletto” stabbing. The Recorder of Manchester, Judge Nicholas Dean KC at Manchester Crown Court 19th June 2023. A musician who stabbed a student to death with a 13-inch ‘mafia stiletto’ knife after a comment over a skateboard was jailed for 15 years.

Government’s Rwanda asylum plan is unlawful, Court of Appeal rules. 29 June Royal Courts of Justice. Lord Burnett, the Lord Chief Justice, Master of the Rolls Sir Geoffrey Vos and Lord Justice Underhill.

Gunman who killed Elle Edwards in Christmas Eve pub shooting jailed for at least 48 years. Mr Justice Goose 8 Jul 2023 at Liverpool Crown Court. A gunman who shot dead a 26-year-old beautician when he opened fire on a packed pub on Christmas Eve was jailed for a minimum of 48 years.

People smuggler jailed for more than 12 years over Essex lorry deaths. Mr Justice Garnham 14 Jul 2023 at the Central Criminal Court. A people smuggler was jailed for more than 12 years for the manslaughter of 39 migrants who were found dead in a lorry trailer in Essex in 2019.

Teens sentenced to total of 34 years for mistaken identity knife murder. Mr Justice Choudhury at Wolverhampton Crown Court 14 Jul 2023. Two teenagers were jailed for a total of at least 34 years for the murder of 16-year-old in a mistaken identity attack. Pradjeet Veadhasa and Sukhman Shergill, both 17, stabbed Ronan Kanda to death close to his family home in Wolverhampton in June 2022.

Whole life term for killer who shot police officer Matt Ratana. Mr Justice Johnson at Northampton Combined Crown and County Courts. 27 July 2023. A gun fanatic who shot dead a Metropolitan Police custody sergeant after smuggling a gun into a holding cell was handed a whole life jail sentence. Louis De Zoysa, 26, opened fire on Matt Ratana without warning using a legally-bought antique revolver and homemade bullets, causing a fatal wound to his heart and lung. Sgt Ratana, 54, later died in hospital.

Rape conviction quashed for man who spent 17 years in jail. 28th July 2023 at the Royal Courts of Justice London. Lord Justice Holroyde with Mr Justice Goose and Sir Robin Spencer. A man who served 17 years in prison had his rape conviction overturned after fresh DNA evidence emerged linking another suspect to the crime. Andrew Malkinson, now 57, was jailed for life with a minimum term of seven years in 2004 after he was found guilty of the attack on a woman in Salford, Greater Manchester – but he stayed in jail for another decade because he maintained his innocence.

Operators fined £14m over Croydon tram disaster failings. Mr Justice Fraser at the Central Criminal Court, 28th July 2023. Tram operators were fined a total of £14m after seven people were killed when a tram crashed in Croydon, south London. Transport for London was fined £10m and Tram Operations Limited was fined £4m for failing in their health and safety duties.

Stepfather and mother jailed over brutal death of baby Jacob Crouch. Mr Justice Kerr at Derby Combined Court Centre 4th August 2023. Craig Crouch, 39, was convicted of murder over a final, fatal attack on the child at his home in Linton, Derbyshire, in December 2020 and jailed for at least 28 years. His partner and Jacob’s mother Gemma Barton, 33, was cleared of murder and manslaughter but found guilty of causing or allowing the infant’s death following a trial at Derby Crown Court. Barton received a total sentence of 10 years.

Killer nurse Lucy Letby gets 14 whole-life sentences. Mr Justice Goss at Manchester Crown Court 21st August 2023. Serial killer nurse Lucy Letby will never be released from prison after she was given 14 whole-life orders for murdering seven babies and attempting to murder six others. The former neonatal nurse, 33, fatally injected seven infants with air, tried to kill two others by lacing their feeding bags with insulin and attempted to force a tube down another’s throat.

Expense fraud MP Jared O’Mara loses bid to appeal jail term. Royal Courts of Justice, Court of Appeal: Criminal Division 27 Sept 2023. The 41 year old former MP had been jailed for fraud and lost a legal bid to challenge his four-year jail term. He was convicted of six counts of fraud following a trial at Leeds Crown Court. He had tried to obtain £52,000 of taxpayers’ money to fund a cocaine habit by submitting bogus claims for parliamentary expenses. Mrs Justice Lambert, sitting with Lord Justice Holroyde and Mr Justice Jeremy Baker rejected permission to appeal saying there was “no arguable ground that the sentence was manifestly excessive,” and it was “wholly proportionate” to the offences committed.

Dame Sue Carr sworn in as first Lady Chief Justice of England and Wales at the Royal Courts of Justice 2nd October 2023. She succeeded Lord Burnett of Maldon, who had held the post since 2017, and became the 98th person – and the first woman – to be appointed head of the judiciary and president of the courts. Speeches were delivered by Master of the Rolls Sir Geoffrey Vos, Lord Chancellor Alex Chalk KC MP, Attorney General Victoria Prentis KC MP, Chairman of the Bar Nick Vineall KC and Law Society President Lubna Shuja.

Windsor Castle intruder gets nine years’ custody for plot to kill the Queen. Mr Justice Hilliard at the Central Criminal Court 6th October 2023. A former supermarket worker who plotted to assassinate the late Queen Elizabeth II was sentenced to nine years in custody – but was told he will remain in hospital until he is deemed fit enough to go to prison. Jaswant Singh Chail, 21, scaled the perimeter of the Windsor Castle grounds with a nylon rope ladder on Christmas Day 2021 armed with a loaded crossbow while wearing a metal Star Wars-inspired mask. He had previously unsuccessfully applied for positions within the Ministry of Defence Police (MDP), the British Army, the Royal Marines, the Royal Navy, and the Grenadier Guards in a bid to get close to the Royal Family.

An example of a ruling from the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) in July 2022 when the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales presented judgement in linked appeals concerning the issue of ‘whole life terms.’ The appellants included Metropolitan Police officer Wayne Couzens convicted of the murder of Sarah Everard.

What is the current law in respect of broadcasting the courts in England and Wales?

The new edition of the Judicial College Guidelines on reporting restrictions in the Crown Court (2022) sets this out under section 5(7) at pages 45 and 46:-

Live-streaming, broadcast and electronic transmission of court proceedings

The statutory prohibitions on the recording and transmission of court proceedings do not apply to the transmission of video and audio of court hearings into a second courtroom, or to another location in England and Wales which is designated as an extension of the court. Not infrequently in criminal proceedings which attract a high level of public and press interest a second courtroom will be made available to permit a greater number of people to follow the proceedings in this way.

Until 2022, however, the general rule was that the statutory prohibitions on taking and publishing photographic images and sound recordings of court proceedings meant that courts had no power to allow their proceedings to be electronically transmitted to the general public. Any exception to this general prohibition requires further legislation.

There are four exceptions where Parliament has intervened to permit the live-streaming or electronic transmission of court proceedings.

- First, s.47 Constitutional Reform Act 2005 creates an exception to the general rule for proceedings in the Supreme Court, which are broadcast online on the Supreme Court Live service.209

- Secondly, the Crime and Courts Act 2013 s.32 empowers the Lord Chancellor to make regulations disapplying the prohibitions on making sound recordings and photographic images, thereby permitting the live-streaming of court proceedings. To date, orders have been made permitting the live-streaming of:

- Public hearings before the full court of the Court of Appeal.

- Sentencing remarks of certain specified judges in the Crown Court, with the permission of the relevant judge.

- Thirdly, the Coronavirus Act 2020 made temporary amendments to the Courts Act 2003, in light of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, to enable certain criminal proceedings to be conducted by means of video or audio link and to permit the ‘broadcast’ of criminal proceedings conducted wholly by means of video or audio, for the purpose of enabling members of the public to see and hear the proceedings. As this power was limited to proceedings conducted ‘wholly’ by video or audio link, it follows that it did not confer power to permit live-streaming of criminal court proceedings which took place in person, or partly in person. This power did not allow a court conducting a fully remote hearing to permit a TV production company to record and then re-broadcast the proceedings.214

- Fourthly, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 replaces the temporary powers under the Coronavirus Act with permanent amendments to the CJA 1925, CCA 1981 and the Courts Act 2003. These allow the Lord Chancellor to empower the Court to direct the electronic transmission of images or sounds of proceedings of all kinds for the purpose of enabling persons not taking part in the proceedings to watch or listen to them, though onward recording and broadcasting is prohibited.

There is now an extensive infrastructure of televised broadcasting of Appeal Court Civil Division cases from the Royal Courts of Justice with streaming on YouTube though permission is not given for the material to be broadcast and re-used by the media:

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 63

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 70

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 71

Court of Appeal Civil Division – Court 73

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 74

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 75

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 76

On 28th July 2023 ITN’s head of legal and compliance John Battle wrote an article for Press Gazette on how the success of filming in UK courtrooms is restoring trust in justice: ‘Cameras in courts one year on: An unqualified success.’ See: https://pressgazette.co.uk/comment-analysis/cameras-in-courts-one-year-on-an-unqualified-success/

Two judges whose sentencing has featured in live televised hearings in the past year, His Honour Judge Mark Lucraft, the Recorder of London, and Mrs Justice Cheema Grubb, have offered their views on the project in a Ministry of Justice media release: ‘One year of broadcasting of sentencing remarks in the Crown Court.’

See: https://www.judiciary.uk/one-year-of-broadcasting-of-sentencing-remarks-in-the-crown-court/

Legal journalist Joshua Rozenberg KC has also written an excellent analysis and review of one year of televising the sentencing in English courts for Law Society Gazette: ‘Letting the public see how the public law works.’ (pages 12 to 13)

The outgoing Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales Lord Burnett has also been making his views on Open Justice and televising the courts in a speech to the Commonwealth Magistrates’ and Judges’ Association in Cardiff in September 2023.

He said: “The question when considering the live-streaming or broadcasting of additional types of case or parts of cases, in my view, should be: why not?”

He supported the common law tradition of Open Justice in identifying judges and parties and resisting anonymization which is the practice in civil and Roman law jurisdictions.

He observed the European Court of Human Rights had not named the duty judge who temporarily prevented the UK from sending asylum-seekers to Rwanda last summer — “something that is alien to the common law tradition.”

See: London Evening Standard 12th September 2023 ‘Strong argument to go further with cameras in courts, says Lord Chief Justice. Lord Burnett said the broadcasting of sentencing in some criminal cases had been ‘successful beyond our expectations’.

Also reported in Standard’s sister online national publication The Independent.

Ministry of Justice Open Justice Consultation 2023

In May 2023, the Ministry of Justice opened a consultation on Open Justice. See: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/open-justice-the-way-forward/call-for-evidence-document-open-justice-the-way-forward

A research document ‘Open Justice: the way forward Call for Evidence’ was released 10th May at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1155744/open-justice-cfe.pdf

The call for evidence ends 7th September 2023 and invites contributions on a wide range of topics: Open Justice; listings; accessing courts and tribunals; remote observations and livestreaming; broadcasting; Single Justice Procedure; publication of judgments and sentencing remarks; access to court documents and information; data access and reuse; and public legal education.

See Law Society Gazette ‘Court photography ban under review in transparency drive’ at: https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/practice/court-photography-ban-under-review-in-transparency-drive/5116009.article

Media Law pdf file briefing on this subject

Parole hearings to be heard in public for the first time

Victims, members of the public and the media will be able to ask for a parole hearing to be heard in public for the first time, following law changes being made 30th June 2022.

See: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/parole-hearings-to-be-heard-in-public-for-the-first-time

Came into effect 21st July 2022. 1. Anyone will be able to apply for a public hearing, with the Parole Board making the final decision on whether to do so. 2. These decisions will consider the welfare and interest of victims and reach a conclusion based on the ‘interests of justice’.

See: The Parole Board (Amendment) Rules 2022

‘An oral hearing (including a directions hearing or case management conference) must be held in private unless the Board chair considers, on their own initiative or on an application to the Board, that it is in the interests of justice for the oral hearing to be held in public.

(3A) Any application for an oral hearing to be held in public under paragraph (3) may not be made later than 12 weeks before the date allocated for the oral hearing.

(3B) If an oral hearing is held in public, the panel chair or duty member may give a direction that part of the oral hearing is to be held in private.’

The first time a Parole Board hearing was reported by the media was December 12th 2022 and concerned convicted murder killer 79 year old Russell Causley.

The decision to have this hearing effectively in public with contemporaneous reporting by journalists was made by Caroline Corby The Chair of the Parole Board for England and Wales 7th September 2022.

It was reported Causley told ‘Britain’s first public parole hearing’ that he burned her body in his garden and disposed of the ashen remains on roadsides and hedgerows

• Causley, 79, killed his wife in 1985 but had never revealed where her body lies

• He told a public parole hearing he burned Carole Packman’s body in his garden

• Then he spread her ashen remains on roadsides and hedgerows in Bournemouth

• Hearing allows the parole board to establish if Causley would be a risk if released

The hearing took place at Lewes prison in East Sussex with relatives, members of the public and journalists allowed to watch the proceedings on a live videolink from the Parole Board’s offices in Canary Wharf, London.

See: ‘First public parole hearing following government reforms.’

Legal journalist Joshua Rozenberg says he was the first journalist allowed to observe a Parole Board hearing for BBC Radio 4’s Law In Action programme in 2020. He was not permitted to identify the prisoner involved.

A further Parole Board hearing has been heard in public with attendance by journalists and members of the public at the Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand London in the case of Charles Bronson in March 2023.

‘Members of the press and public could watch the latest proceedings – taking place in prison – on a live stream from the Royal Courts of Justice in central London’

See Evening Standard report ‘Charles Bronson describes ‘rumble of his life’ prison fight as parole panel told he wouldn’t cope with release. He is only the second inmate in UK legal history to have his case heard in public.’

Keeping reporting files and the importance of accurate and professional shorthand as a journalist/reporting skill when covering the courts.

A High Court ruling on 7th December 2022 is a substantial victory for a freelance court reporter in London whose diligent professionalism in keeping accurate and dated notebooks and applying the Teeline shorthand kill in his work clearly contributed to his defence.

Tony Palmer is described in the ruling of ABC v Palmer [2022] EWHC 3128 (KB) (07 December 2022) as ‘a freelance journalist who is a member of the National Union of Journalists and who sells reports of court hearings to national newspapers and posts them on a blog he runs called Square Mile News. The Claimant brings this action as a result of a report by the Defendant which purported to be of the hearing of her case at the Magistrates Court and which he posted on his blog, Square Mile News (“the Blog Post”) dated 13 May 2015.’

The case relates to a report from a magistrates court case where the claimant pleaded guilty to fraud and received a suspended prison sentence. Seven years after reporting her case and publishing it, Mr Palmer faced litigation for misuse of private information, harassment, breach of the General Data Protection Regulation, and a claim from the women that she had the right to be forgotten because her conviction was now spent under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act.

Mr Palmer successfully defended himself and the action against him did not succeed on any of the grounds.

The following quotations from Mr Justice Griffiths demonstrate how well Mr Palmer accomplished his assertion of not only his professionalism but the right of journalists to report open criminal court hearings fairly and accurately:

Paragraph 11:-

‘I accept Mr Palmer’s evidence that he makes his living as a journalist and court reporter. He works alone. He showed me a National Union of Journalists press card valid for the period including the date of Ms C’s plea and sentencing hearing. He has been a journalist since 1988. Apart from his working experience, his only training has been in Teeline shorthand, which he learned in about 2010. He sells stories to national newspapers, such as the Sun, the Mirror, the Star, the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, the Times, the Telegraph and the Evening Standard. He showed me some articles with his name “Tony Palmer” as the byline, reporting court cases. He also posts court reports on his blog, Square Mile News, a website which he runs alone and is proud of (“SMN”). When he has failed to gain the interest of the printed press for his reports, he leaves them on SMN. His SMN reports may state, as the Blog Post in issue in this case did, “Exclusivity Option – Contact [email address] for sole rights to story and removal”…He explained that the notice on SMN was to encourage national papers to buy and run his stories, and to assure them that, if they did, they could have them as exclusives and the stories would be removed from SMN in order to give them that exclusivity.’

The claimant alleged Mr Palmer was not in court to report her case. He was able to counter this because between paragraphs 14 and 17:

‘Mr Palmer’s evidence is, however, compelling on this point. I was shown an email from HMCTS sending him the Magistrates Court list for the week commencing 12 May 2015 and I was shown the attached copy list itself, which included both Ms C’s case and another case in the same building on the same day which Mr Palmer reported on, under his Tony Palmer byline, in a national newspaper. He got the cause list in order to spot cases that it might be worth his while to attend and report on.

I was also shown his Teeline shorthand notes of the hearing, and the original notebook from which the photocopies in the bundle were made. In his oral evidence, he read out the meaning of the notes and it was obvious (Teeline being a relatively simple system in which many characters are self-explanatory even to the untrained reader) that his explanation of what they meant was correct. The notes sounded exactly as one would expect a court hearing to go, starting with the submissions of the prosecutor, continuing with the submissions of the defence, and concluding with the sentencing remarks of the District Judge.

I was also shown copies of photographs taken by Mr Palmer of defendants whose stories he had decided to write up which he took outside court. He explained that having a photograph enhances the value and interest of his stories to potential buyers from the national newspapers. These photographs were all grouped together on his Apple Mac (in a screenshot) under the correct date 12 May 2015 in a series of 8 photographs. The first 3 were of the person in the other case on that day which Mr Palmer did successfully sell as a bylined report in a national paper, which I was shown. The next four of the Claimant, of which the most distinct was used in the Blog Post.

I am therefore satisfied on the evidence that Mr Palmer did personally attend the hearing of Ms C’s case as he claims, that he took a contemporaneous Teeline note of the proceedings, and that he took the photograph of Ms C himself. She accepts that it is a photograph of her.’

The claimant also challenged the accuracy of Mr Palmer’s reporting. The High Court judge examined and analysed his notebook meticulously. Again the quality of his journalism and reporting are commendably evaluated and recognised across paragraphs 20 to 26:

‘The notes start with the date, 12 May. They note the relevant Magistrates Court, using the first three letters of the place (which I will not set out) as an obvious abbreviation. They note cases from the cause list which might be of interest to Mr Palmer, including, specifically, the case which he did get published in a national paper, and Ms C’s case.

Then the name of the prosecutor in Ms C’s case, Sue Obeney, is noted. I accept Mr Palmer’s evidence that he either got this name by asking on the day, or because she was the regular prosecutor for local authorities in this court, and he was himself a regular reporter in this court (as press reports corroborate), and knew her name before the case began.

After notes of the cases before Ms C’s case (including the case which he successfully sold under his byline), Ms C’s surname is in the notes. The prosecution opening of the facts is then noted down. These notes cover 3 pages (starting in the middle of electronic page 127 of trial bundle “Evidence 2”, and ending in the middle of page 130, with prosecution costs claimed at £26,500). They closely correspond to what Mr Palmer subsequently included in his Blog Post report.

From the middle of page 130 to the bottom of page 131 are Mr Palmer’s Teeline notes of the defence submissions on behalf of Ms C. They begin (picking up from something noted in the prosecution opening of the facts) “She does have OCD, mental health issues”, “she ended up having to share with other people, and her OCD”, “She claimed for borough she wasn’t living in to top up her benefit to allow her to reside in her self contained flat”, “now receives extra benefit for OCD”, “£5,300 overpayment”, “PIP [Personal Independence Payment] eligible”, “£325 per week extra PIP”, “£20 disability”, “Housing Benefit now £250 per week”, “She’s rated at high end of disability”, “She cares for her younger brother, and has been given two-bedroom flat so her 11 year old brother can live with her”, “Employment Support Allowance of £300 per fortnight”.

I am satisfied that all these things were said, as noted, by Ms C’s own legal representative in open court when making submissions on her behalf to the District Judge. I reject Ms C’s claim that they were not said and that there was no reference to her OCD or mental health issues, or to her brother.

Finally, the Teeline note of this hearing concludes (p 132 of the electronic bundle) with the sentencing remarks of “Wattam”, i.e. District Judge Wattam. There is a note of him referring to “the significant degree of sophistication and you supplied false details. Your offending was quite deliberate and dishonest.” The sentence passed is noted (correctly) as “4 months [imprisonment] suspended for 12 months”, with “£25 costs, £80 victim surcharge”. The name of Ms C’s legal representative is noted, again correctly, as “Ms Goodwin, defence”.

The hearing took place, as I have said, on 12 May 2015.’

When Mr Justice Griffiths analysed his published report of the hearing he said: ‘I am satisfied that this was an honest and accurate report of the hearing.’

At paragraph 84, the judge vindicated his decision to repost the report after the claimant began making allegations about his reporting:

‘I consider that the necessary exercise of Mr Palmer’s legitimate rights of freedom of expression and information outweighed Ms C’s rights to privacy and other rights at this time, because she was actively making false claims about him and about events which he had witnessed. The Blog Post was his version of events, and it was a true version. I also take into account that the harm to her was limited to her own reaction to knowing the Blog Post was up, since no-one else was interested in it and no-one else, so far as the evidence shows, was looking at it so many years after 2015, except in connection with Ms C’s own complaints. This point is particularly strong since Google had de-listed it in 2017 and it was therefore not easy to find.’

The significance of his case is the importance of court reporters, and indeed all journalists, in maintaining their professional discipline in keeping accurate, dated and reliable shorthand notes of their work. Sam Brookman analysed this case for the The Hold The Front Page Jaffa media law column 20th December 2022.

Sam Brookman rightly sees significance in the Judge’s following observation at paragraph 75:

‘The essential record in this respect was his reporter’s notebook. He retains all of these routinely, and operates on the basis that they should be kept for at least 7 years. That is in my judgment reasonable, given that normal limitation periods are 6 years and claims may be issued at the end of that period and not served immediately. Mr Palmer’s retention of records has enabled this trial to be conducted on the basis of good evidence. It is fortunate that he did retain his notebook, in particular. Otherwise, the untrue evidence of Ms C that he was not there, and that things that he reported were never said in court, might not have been so easily disproved. When, as in this case, there is a stark conflict of oral evidence, the retention of documentary records is vindicated.’

Ms Brookman commends the journalist defendant since: ‘the fact remains Mr. Palmer was able to defeat a highly unmeritorious claim based on the Claimant’s “untrue evidence”, because he had been so meticulous in keeping his background materials.’

Sam Brookman concludes her column by saying ‘if you ask me how long a notebook should be kept, my answer will always be: “the longer the better”!’

I am pleased to say that in the printed text of the book at 2.15 on page 86 I recommended: ‘Always keep your notes and background papers on any cases you report for up to six years after the event. There is a case for keeping them until you retire.’

Ethical representation of the identity of transgender defendants and other participants in court reporting

Professional journalists and student journalists, particularly in universities, will be very much aware of the acute debates taking place about proper vocabulary and references to gender identities.

The issue is taken so seriously in professional and institutional life individuals found to have disrespected fair and respectful wishes on gender identification have faced disciplinary proceedings and dismissal.

There is understandable anxiety on the part of trainee journalists about the expectations of how defendants and other participants represent themselves in court, how they are referred to in the legal proceedings and how this must be properly and fairly reported.

IPSO (The Independent Press Standards Organisation) has published fresh draft guidance on reporting of sex and gender identity, which contains advice for newsrooms on covering court cases involving transgender and gender-diverse defendants.

IPSO is seeking consultation before finalising the guidance.

Journalists are being urged to take account of trans defendants’ gender at the time they offended.

IPSO Draft guidance on reporting of sex and gender identity

See: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2302/ipso-draft-guidance-on-reporting-of-sex-and-gender-identity.pdf

The key points arising from the guidance on court reporting recommend:

- Taking into account and respecting the way a defendant says they wish to be identified in the court proceedings, including the name used and pronoun used by court officials and/or any witnesses;

- Taking account of the defendant’s gender identity at the time of the alleged crime;

- Considering any guidance provided by the court about a defendant’s gender identity;

- Evaluating the public interest in reporting the gender identity and any transition in the context of protecting public health or safety particularly in respect of the need to ensure accuracy when reporting a major news event;

- Considering the significance of the charges the defendant faces and whether gender identity is relevant to the case brought by the prosecution and the defence and/or mitigation provided during the trial.

The stalwarts of legally safe court reporting: accuracy, fairness and attribution are effective lines of protection from what would be secondary media law complaints to regulatory bodies. However, it might be argued there are still areas of discretion which should be determined by the exercise of an individual’s conscience and the freedom of expression prerogative.

Primary media law litigation could arise if gender transitioning and identity information about an individual has not been put into the public domain by the individual concerned, and if the journalist and publisher cannot show by documentary trail they have carried out a balancing act analysis of whether in reporting gender identity the degree of intrusion is proportionate to the public interest being served.

The navigation of this area is clearly controversial. Dr Amy Binns and Sophie Arnold sought to research the subject and produced guidance on covering court cases involving transgender defendants.

But this was removed by the University of Central Lancashire after its publication online following complaints made to the university.

See the following articles and case law for further guidance and background:

Law Column: IPSO and reporting on sex and gender identity by Sam Brookman Published 21 Feb 2023 https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2023/news/law-column-ipso-and-reporting-on-sex-and-gender-identity/

Journalists urged to take account of trans defendants’ gender at time they offended https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2023/news/pronouns-and-transgender-defendants-feature-in-press-watchdogs-new-guidance/

IPSO commissions research into standards of UK media reporting on transgender issues https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/ipso-commissions-research-into-standards-of-uk-media-reporting-on-transgender-issues/

New guidance launched to aid reporting on transgender defendants https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2022/news/new-guidance-launched-in-bid-to-aid-reporting-on-transgender-defendants/

Guidance on covering transgender defendants removed after complaints https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2022/news/guidance-on-covering-transgender-defendants-removed-after-complaints/

Editor and reporter leave weekly after transgender column controversy by David Sharman Published 13 Nov 2017 Last updated 17 Nov 2017 https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2017/news/editor-and-reporter-leave-weekly-after-transgender-column-controversy/

Press Gazette: ‘Kentish Gazette transgender article was wrong – but journalists should not be sacked for exercising freedom of speech’ https://pressgazette.co.uk/publishers/regional-newspapers/kentish-gazette-transgender-article-was-wrong-but-journalists-should-not-be-sacked-for-exercising-freedom-of-speech/

Journalist who launched LGBTQ+ network leaves regional press for national role https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2023/news/journalist-who-launched-lgbtq-network-leaves-regional-press-for-national-role/

Press Gazette ‘Transgender ex-Times journalist loses discrimination claim against paper’ https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/transgender-ex-times-journalist-loses-discrimination-claim-against-paper/

Press Gazette “Columnist James Wong leaves The Observer and claims ‘institutionalised transphobia.” https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/james-wong-observer-social-media-transphobia/

Media wins right to name transgender man battling to be named ‘father’ on own child’s birth certificate https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/media-wins-right-to-name-transgender-man-battling-to-be-named-father-on-own-childs-birth-certificate/

TT, R (on the application of) v The Registrar General for England and Wales [2019] EWHC 2384 (Fam) (25 September 2019) https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Fam/2019/2384.html

Courts and Tribunals Judiciary July 2022 ‘interim revision of the Equal Treatment Bench Book issued’ https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Equal-Treatment-Bench-Book-July-2022-revision-2.pdf

The Crown Prosecution Service Trans Equality Statement https://www.cps.gov.uk/publication/trans-equality-statement and https://www.cps.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/publications/Trans-equality-statement.pdf

Relevant IPSO rulings

00804-20 Smith v The Herald Decision: No breach – after investigation https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=00804-20 Daily newspaper cleared over SNP trans row story https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2020/news/daily-newspaper-cleared-over-snp-trans-row-story/

09159-19 Fair Play for Women v kentlive.news Decision: Breach – sanction: action as offered by publication https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=09159-19 Watchdog raps news site over ‘transphobic abuse’ claim https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2020/news/ipso-raps-news-site-for-reporting-alleged-transphobic-abuse-as-fact/

00572-15 Trans Media Watch v The Sun Decision: Breach – sanction: publication of adjudication https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=00572-15

01972-22 The Radcliffe School v miltonkeynes.co.uk Decision: Breach – sanction: publication of adjudication https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=01972-22

Resolution Statement – 06439-21 Pascoe v spectator.co.uk Decision: Resolved – IPSO mediation https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=06439-21

09309-21 A woman v Daily Mail Decision: No breach – after investigation https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=09309-21

01695-21 Parrott v Norwich Evening News Decision: Breach – sanction: action as offered by publication https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=01695-21

Anonymity in the Magistrates Court, Open Justice victory for journalists 17th March 2023 ruling of the Administrative High Court

This was a Section 11 1981 Contempt of Court Act order made at Westminster Magistrates for withholding a name in a Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 hearing.

The challenge was first made by submissions in court from Martin Bentham, Home Affairs Editor of the Evening Standard and Koos Couvée, Senior Reporter with ACAMS MONEYLAUNDRERING.COM. But they were only able to make their submissions after the hearing applying for the reporting restriction order was held in private from which they were excluded. And the notice news organisations were given about the order being applied for was distributed the night before.

The issue was further taken up by the BBC with a formal application to discharge the order. The journalist Martin Bentham and Leading Counsel for the BBC, Jude Bunting KC (instructed by in-house legal team) made submissions and successfully persuaded the District judge to lift the order.

The Judicial Review was made by the person who sought anonymity ‘MNL’. In an important ruling for professional journalism, the High Court ruled that Open Justice had to prevail in this case over Article 8 privacy rights.

MNL, R (On the Application Of) v Westminster Magistrates’ Court [2023] EWHC 587 (Admin) (17 March 2023)

See: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2023/587.html

And the judgement by Lord Justice Warby and Mr Justice Mostyn includes persuasive observations on journalists’ and news publishers’ rights to be given proper notice and the opportunity to challenge such orders when they are applied for.

Lord Justice Warby’s introduction- paragraphs 1 and 2

- This is a claim for judicial review of a decision of the Westminster Magistrates’ Court to lift an order anonymising the claimant in connection with a claim for forfeiture of assets brought by the National Crime Agency (the NCA) against three other individuals under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. The main issue is whether the judge erred in law when resolving a conflict between the imperatives of open justice and the rights of a non-party to respect for his private life.

- The claimant was neither a party nor a witness in the forfeiture proceedings, but he does have some connections with the respondents to those proceedings. Before the hearing began, having learned that prejudicial references to him were likely to be made and fearing the reputational consequences, he applied for an anonymity order. The District Judge made such an order, heard the forfeiture proceedings and gave a public judgment in favour of the NCA which referred to the claimant but did not name him. Thereafter, on the application of the BBC the judge discharged his earlier order. The claimant challenges the judge’s decision as flawed in law. He contends that we should set aside the decision of the judge, re-make the decision and restore the anonymity order.

Key ratio decidedi at paragraph 41, sub-paragraphs 5 to 7:

(5) The next stage is the balancing exercise. Both the judge’s decisions expressly turned on whether it was “necessary and proportionate” to grant anonymity. That language clearly reflects a Convention analysis and the balancing process which the judge was required to undertake. The question implicit in the judge’s reasoning process is whether the consequences of disclosure would be so serious an interference with the claimant’s rights that it was necessary and proportionate to interfere with the ordinary rule of open justice. It is clear enough, in my view, that he was engaging in a process of evaluating the claimant’s case against the weighty imperatives of open justice.

(6) It is in that context that the judge rightly addressed the question of whether the claimant had adduced “clear and cogent evidence”. He was considering whether it had been shown that the balance fell in favour of anonymity. The cases all show that this question is not to be answered on the basis of “rival generalities” but instead by a close examination of the weight to be given to the specific rights that are at stake on the facts of the case. That is why “clear and cogent evidence” is needed. This requirement reflects both the older common law authorities and the more modern cases. In Scott v Scott at p438 Viscount Haldane held that the court had no power to depart from open justice “unless it be strictly necessary”; the applicant “must make out his case strictly, and bring it up to the standard which the underlying principle requires”. Rai (CA) is authority that the same is true of a case that relies on Article 8. The Practice Guidance is to the same effect and cites many modern authorities in support of that proposition. These include JIH v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2011] 1 WLR 1645 where, in an often-cited passage, Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury said at [22]:

“Where, as here, the basis for any claimed restriction ultimately rests on a judicial assessment, it is therefore essential that (a) the judge is first satisfied that the facts and circumstances of the case are sufficiently strong to justify encroaching on the open justice rule …”

(7) In my opinion, the closing passage of the judgment under review reflects the conclusion arrived at by the judge after conducting the necessary balancing process. This was that, in the light of all the facts and circumstances that were apparent to him at that time, the derogation from open justice that anonymity would represent was no longer shown to be justified as both necessary for the protection of the claimant’s Article 8 rights and proportionate to that aim.’

Mr Justice Mostyn’s ruling in paragraphs 48 to 56 set out what was wrong about the procedure and denail of natural justice to the press/media:

48 In DPP v Shannon [1975] AC 717, 766 Lord Simon of Glaisdale recalled that the father of English legal history, F.W. Maitland, “was wont to observe how rules of substantive law have seemed to grow in the interstices of procedure”[1].

49 Procedural rules exist for a purpose, and that purpose is to ensure that every legal cause is despatched not merely efficiently, but fairly. Procedural rules are not so much directed to ensuring that the content of a judicial decision is just – that is what the substantive law achieves – but that the way it is reached is fair. In their interstices they incorporate and promulgate the elementary rule of natural justice, mirrored in Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights, that everyone has the right to a fair hearing.

50 A fair hearing means not only that your judge is not biased (nemo iudex in causa sua) but that you are heard (audi alteram partem). And being heard means not merely that you are allowed to participate in a hearing that affects you, but, critically, that you are given reasonable notice of it.

51 We know that the claimant was warned in the second half of September 2021 that the NCA intended to make allegations against him in forfeiture proceedings brought against monies held in UK bank accounts by members of JF’s family. The claimant therefore had over a month to take whatever steps he judged necessary to protect himself. The choice he made was to apply for a reporting restriction order (“RRO”) on the afternoon of 28 October 2021. Astonishingly, that was the day immediately before the commencement of the substantive forfeiture trial. No explanation has been offered for this delay.

52 The notice given to the NCA was therefore not even of one clear day. It was so short that had the NCA decided to contest the application it is doubtful that it would have been able to assemble its case in the time left. However, that evening the NCA agreed not to refer to the claimant by name in the proceedings.

53 The press were not served until that evening, and so, to all intents and purposes had no notice at all.

54 The following day the application was heard in private. The press were not allowed into the hearing. The NCA did not contest the application. Obviously, the Respondents (JF’s family members) did not contest it. The press were then provided with a copy of the draft order and two journalists were allowed to make oral submissions after the hearing had concluded, and without having heard the submissions on behalf of the claimant. The order records that the court only heard counsel for the claimant and for the parties but the note of the judge’s judgment states that he heard detailed submissions from the press. The procedure is utterly bizarre.

55 The consequence of what looks like a strategic decision to give almost the shortest possible notice to the NCA, and in reality none to the press, was that the application for the RRO was effectively uncontested. Allowing the press to make submissions after the hearing was over does not amount to much of a contest.

56 In my judgment, this process did not meet the requirements of natural justice.

At paragraph 75 he strongly criticised the decision to hold the reporting restriction order application in private with the press excluded:

75. The RRO application was heard by the judge in private in the absence of the press. We have not been told how that came about, but this was an exceptional course to take and could only be justified if the application could not fairly be heard in the presence of the press. Ordinarily, that will not be so as the media will offer undertakings not to publish the hearing papers or, if necessary, reporting restrictions can be imposed to protect any confidential evidence. It is not as if this was one of those cases where the evidence disclosed intimate personal information which the claimant could justifiably wish to withhold from the media. I do not understand why the press were not able to attend the hearing and were only allowed to make oral submissions after it was over.

He further adds at paragraphs 90 and 91:

’90 …I am not surprised, on the facts of this case, that the initial anonymity order was discharged.

91 My only surprise is that the anonymity order was granted in the first place on 29 October 2021. In my judgment, for reasons of procedural unfairness as well as a distinct lack of merit, it should never have been granted.’

This is a very significant victory by the BBC on behalf of journalism and Open Justice rights in the UK and great respect and thanks are due to journalists Martin Bentham and Koos Couvée for doing their best to challenge and resist what was going on at Court and then the BBC and KC Jude Bunting for the strength of advocacy provided at Westminster Magistrates and the High Court.

The ruling has been analysed comprehensively by media lawyer Sam Brookman for Hold The Front Page Jaffa Law Column: ‘A victory for open justice as Judicial Review fails.’ See: https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2023/news/law-column-a-victory-for-open-justice-as-judicial-review-fails/

The case has also been reported by Press Gazette: “BBC and Evening Standard win right to identify man in ‘dirty money’ trial.” See: https://pressgazette.co.uk/media_law/azerbaijani-laundromat-court-open-justice/

After the media groups challenging the order successfully resisted an appeal on May 16th 2023, it was possible to identify ‘MNL’ and this resulted in high profile coverage in the London Evening Standard and BBC programmes and online.

See: ‘Millionaire Tory donor and business tycoon Javad Marandi linked to major money laundering operation’ at: https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/conservative-tory-party-donor-javad-marandi-conran-shop-anya-hindmarch-money-laundering-nca-b1081279.html

BBC News ‘Javad Marandi: Tory donor’s link to massive money laundering probe.’ See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-61264369

Press Gazette: “BBC and Evening Standard win right to identify man in ‘dirty money’ trial.” See: https://pressgazette.co.uk/media_law/azerbaijani-laundromat-court-open-justice/

Managing the placement of students to experience court reporting- some advice and resources.

The UK’s legal system needs public confidence and support. Access, qualitative, fair and accurate reporting in the media is a critical factor in furthering the constitutional principle of Open Justice. I believe universities educating and training journalists can encourage judges and court staff to improve and enhance the achievement of this purpose through active liaison and collaboration.

Journalism university tutors should directly reach out to the presiding judges for local court centres and their senior HMCTS managers. In partnership university and judicial institutions can facilitate and achieve trust, understanding, knowledge and in the end become models for the Open Justice provision.

Arrange a meeting. Discuss what can be achieved. Reach out and collaborate. If your university has a Law Department find out what they do and if lines of communication can be synchronized.

Tutors should be prepared to accompany student groups on any formal visits and if a busy timetable prevents this every time, they should certainly enquire, communicate and provide advance information about the student journalist groups, their purpose and presence, along with reassurance about the quality of education and training in media law being provided to them.

The students need accreditation letters, and when possible student journalist membership press cards from the CIoJ, NUJ and BAJ. (Is there not an advantage in the universities covering the costs for student membership of professional journalism bodies?)

When judges and court staff fully understand that the education and training of student journalists requires attendance and coverage of court hearings and the writing of reports with their assessment, this is more than likely to forge cooperation and most hopefully a symbiosis of appreciation and education. This can surely work both ways.

The USA developed the model many decades ago of media/bench committees at federal, state and city court centres where there would be the opportunity for the various professions to exchange views, thoughts and ideas on how they could all improve and sustain their respective aims. Whatever the decline in the infrastructure of local and regional journalistic coverage, I believe the university journalism and journalism training sectors are in a position to fill the vacuum and revive the function, purpose and extent of court reporting.

Such interaction could also extend to Coroners Courts and Youth Court centres. Yes, only accredited press card carrying professional journalists have access to Youth Courts, but might there be an argument for Youth Courts to permit student journalist reporting presence when accompanied by professional journalist tutors? The Youth Justice system needs understanding particularly at a time when so many young people are the victims and perpetrators of a worrying trend in knife crime.

Student journalists must respect the courtesies and dignity of the court by ensuring they attend on time and avoid excessive disruption of the proceedings when entering and leaving. Only do so during a lull in the proceedings. You should not be moving when the oath is being taken by a witness or juror.

It should go without saying that student journalists must dress smartly and appropriately in this environment. A guide to essential reporting published in 2007 observed: ‘They won’t actually throw you out if you turn up in jeans and a fcuk tee-shirt, but you will find them less than co-operative. Jacket and tie for men, smart outfit for women. No hats or bare shoulders.’

Student reporters should not bring food and drink into the courtroom, and must not use their smartphones and read newspapers, books and magazines during proceedings for personal entertainment. This includes those times when the court is not in session. Lawyers will be still be working in the courtroom.

Student journalists should avoid yawning openly, however boring and soporific the case and submissions. Falling asleep and snoring is another big no-no.

Raucous conversation and talking aloud, smiling and laughter should also be avoided during proceedings and adjournments. If you must talk to a colleague, whisper or write something down on paper. There is a risk that your exaggerated facial expressions could be misinterpreted by the relatives of crime victims and defendants who may be in the public gallery or well of the court.

When the court session begins everyone is expected to stand up when the judge(s) or justices enter and leave the courtroom. It is customary for solicitors, barristers and court officials to bow. You do not have to, but it would not be held against you if you do.

What does the current HMCTS ‘General guidance to staff on supporting media access to courts and tribunals’ say about student journalist/court reporters?

‘Student journalists

Student journalists will often attend court cases or hearings as part of their training. We should support this as one way to encourage greater court reporting. They are not entitled to sit in press seats but should sit in the public gallery where they are entitled to take notes without permission from the court or judge/magistrate. However, in sensitive cases (such as organised crime), it will help the judge and staff to avoid any misunderstanding if they identify themselves in advance to explain that they plan to do so. Student journalists do need to make an application to the court if they want to use text-based devices to communicate from court. If you receive a request from a student journalist, please speak to the judge presiding over

the case or trial. If a lecturer wants to attend court with a group of students

to observe a case or hearing, it is good practice (but not mandatory) to let the court know in advance.’

Here is an outline of the information which can be pulled together about the legal system in the Greater London Area as an example of what can be done regionally in other parts of the UK.

This briefing is provided by pdf file in two column format with contacts and details for the courtss in the London area.

Secondary Media Law Codes and Guidelines

IPSO Editors’ Code of Practice in one page pdf document format https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2032/ecop-2021-ipso-version-pdf.pdf

The Editors’ Codebook 144 pages pdf booklet 2023 edition https://www.editorscode.org.uk/downloads/codebook/codebook-2023.pdf

IMPRESS Standards Guidance and Code 72 page 2023 edition https://www.impress.press/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Impress-Standards-Code.pdf