THE UK MEDIA LAW POCKETBOOK

by Tim Crook

Published by Routledge 30th November 2022

If you are reading and accessing this publication as an e-book such as on the VitalSource platform, please be advised that it is Routledge policy for clickthrough to reach the home page only. However, copying and pasting the url into the address bar of a separate page on your browser usually reaches the full YouTube, Soundcloud and online links.

The companion website pages will contain all of the printed and e-book’s links with accurate click-through and copy and paste properties. Best endeavours will be made to audit, correct and update the links every six months.

Chapter 4

News Gathering, Story Finding and Public Interest

This chapter covers the criminal, civil and regulatory laws affecting journalists and media publishers when reporting in the field, researching stories and the legal and ethical dimensions of what is generally known as ‘the public interest.’

What is the capacity and range of ‘public interest’ as a defence in law and professional ethics?

Analysis and explanation of the criminal offences that can be committed by journalists when reporting and any public interest defences that might be available.

These include phone and computer hacking, bribery and corruption, harassment, and the way UK law protects journalist sources.

What powers do the police have on seizure and search?

What are the journalistic defences?

How does the UK state through criminal prosecutors and courts define the public interest ‘excuse’ when journalists break criminal laws in the process of doing their work?

Video-cast on News Gathering, Story Finding and Public Interest in Media Law

4.0 Bullet points summarizing news-gathering conduct that might breach the criminal law and the status of public interest defences

4.1 Definitions of the public interest

A downloadable sound file exploring press and broadcasting definitions of the public interest

Online Links Printed Book

Pages 152 and 153

Ofcom Broadcasting Code- definition of public interest in Section 8 on Privacy

https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code/section-eight-privacy

BBC’s definition of public interest at Section 1.3 of its Editorial Guidelines

https://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidelines/editorial-standards#publicinterest

CPS Media: Assessing the Public Interest in Cases Affecting the Media

https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/media-assessing-public-interest-cases-affecting-media

4.2 Potential criminal offences affecting news gathering and story finding

Online Links Printed Book

Page 157

Bribery Act 2010

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/23/contents

France v R. [2016] EWCA Crim 1588 (27 October 2016)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Crim/2016/1588.html

NORMAN v. THE UNITED KINGDOM – 41387/17 (Judgment : Remainder inadmissible : Fourth Section) [2021] ECHR 601 (06 July 2021)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2021/601.html

Thomas v News Group Newspapers Ltd & Anor [2001] EWCA Civ 1233 (18 July 2001)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2001/1233.html

4.3 Protecting sources

A downloadable sound file on key statutory and case law protection of sources

Online Links Printed Book

Page 158

Fine Point Films & Anor, Re Judicial Review [2020] NIQB 55 (10 July 2020)

https://www.bailii.org/nie/cases/NIHC/QB/2020/55.html

A woman v Evening Chronicle (Newcastle upon Tyne) July 2006

http://www.pcc.org.uk/cases/adjudicated.html?article=NDA2MQ

A woman v the Halifax Courier IPSO ruling December 2020

https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=05823-20

A man v Central Fife Times & Advertiser IPSO ruling December 2020

https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=10508-20

Page 159

The editorial lessons for the BBC arising out of the Hutton Enquiry

https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/aboutthebbc/insidethebbc/howwework/reports/pdf/neil_report.html

Journalistic excluded material is defined by Part II, section 11 of the Act:

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/60/section/11/enacted

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/60/section/14/enacted

Part II Section 13 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act ‘meaning of journalistic material’

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/60/section/13/enacted

Page 160

Bright, R (on the application of) v Central Criminal Court [2000] EWHC 560 (QB) (21 July 2000)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/QB/2000/560.html

British Sky Broadcasting Ltd & Ors, R (on the application of) v Chelmsford Crown Court [2012] EWHC 1295 (Admin) (17 May 2012)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2012/1295.html

Page 161

GOODWIN v. THE UNITED KINGDOM – 17488/90 [1996] ECHR 16 (27 March 1996)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/1996/16.html

FINANCIAL TIMES LTD AND OTHERS v. THE UNITED KINGDOM – 821/03 [2009] ECHR 2065 (15 December 2009)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2009/2065.html

Page 162

SANOMA UITGEVERS B.V. v. THE NETHERLANDS – 38224/03 [2010] ECHR 1284 (14 September 2010)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2010/1284.html

TELEGRAAF MEDIA NEDERLAND LANDELIJKE MEDIA BV AND OTHERS v. THE NETHERLANDS – 39315/06 – HEJUD [2012] ECHR 1965 (22 November 2012)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2012/1965.html

BECKER v. NORWAY – 21272/12 (Judgment: Violation of Article 10 – Freedom of expression-{general} (Article 10-1 – Freedom of expression Freedom to impart information . . .) [2017] ECHR 834 (05 October 2017)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2017/834.html

Norman v United Kingdom – 41387/17 (Judgment: Remainder inadmissible: Fourth Section) [2021] ECHR 601 (06 July 2021)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2021/601.html

Halet v Luxembourg – 21884/18 (Judgement: No Freedom of expression-{general} : Third Section) French Text [2021] ECHR 388 (11 May 2021)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2021/388.html

Webcast of Grand Chamber Appeal submissions 2 February 2022

Accessible via https://www.echr.coe.int/Pages/home.aspx?p=hearings&c

Page 164

Application for a Production Order under the Terrorism Act 2000. Ruling 22 March 2022 by the Recorder of London.

https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Application-for-a-production-order-under-the-Terrorism-Act-2000.pdf

HTFP Law Column: Journalist succeeds in preventing disclosure of sources 5/04/2022

https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2022/news/law-column-journalist-succeeds-in-preventing-disclosure-of-sources/

Bill of Rights bill 2022

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/58-03/0117/220117.pdf

4.4 Secondary media law and regulation

Online Links Printed Book

Pages 166 and 167

IPSO Case history Pell & Bales v The Sun Decision: No breach – after investigation Relevant code provisions 1 (Accuracy) 2015 10 (Clandestine devices and subterfuge) 2015 Publication The Sun (News UK)

https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=04088-15

Section 8 of Ofcom Broadcasting Code on Privacy 8.12 to 8.15

https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code/section-eight-privacy

Pal v United Kingdom – 44261/19 (Judgment: Article 10 – Freedom of expression-{general} : Fourth Section) [2021] ECHR 990 (30 November 2021)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/ECHR/2021/990.html

Reporter Gareth Davies on winning his two-year battle to expose a fraudster and overturn a police harassment notice

https://pressgazette.co.uk/reporter-gareth-davies-on-winning-his-two-year-battle-to-expose-a-fraudster-and-overturn-a-police-harassment-notice/

BBC Editorial Guidelines. Guidance on secret recording

https://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidance/secret-recording

BBC Editorial Guidelines. Guidance on investigations

https://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidance/investigations

BBC Editorial Guidelines on Privacy, secret recordings and surveillance. 7.3.10 to 7.3.28

https://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/guidelines/privacy/guidelines

Report of the Dyson Investigation into the circumstances by which Martin Bashir secured an interview with Diana Princess of Wales for BBC Panorama in 1995

https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/aboutthebbc/reports/reports/dyson-report-20-may-21.pdf

BBC report 16 September 2021 ‘Martin Bashir: Police take no action over Diana interview’

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-58576095

4.5 Updates and stop press

The legal jeopardy for journalists when arrested while covering news events in the UK.

The widespread criticism of arrests by Hertfordshire police of journalists and photographers covering Just Stop Oil protests, including an LBC/Global reporter is an opportunity to explore the law and ethics over reporters’ rights when covering stories of this kind.

What are the rights of journalists if wrongfully stopped from doing their job by the police, and even worse arrested for doing so?

This does not constitute qualified legal advice, but journalists should always have direct contact with their employer’s lawyers or professional legal advice in the event of arrest while carrying out their work.

It is also recommended that professional journalists covering public news events are members of professional journalist organisations such as the National Union of Journalists (NUJ), Chartered Institute of Journalists (CIoJ) or British Association of Journalists (BAJ).

The UK National Police Chiefs’ Council accredited Press Card states categorically ‘The National Police Chiefs’ Council recognise the holder of this card as a bona fide newsgatherer.’

Furthermore the College of Policing guidance on media relations (updated for 2022) states under the heading ‘Reporting from a scene’:-

‘Reporting or filming from the scene of an incident is part of the media’s role and they should not be prevented from doing so from a public place. Police have no power or moral responsibility to stop the filming or photographing of incidents or police personnel. It is for the media to determine what is published or broadcast, not the police. Once an image has been recorded, the police have no power to seize equipment, or delete or confiscate images or footage, without a court order.’

College of Policing guidance is available online at: https://www.college.police.uk/app/engagement-and-communication/media-relations

The largest police force in the UK is the Metropolitan Police in London who have an online public declaration of media rights for journalists and members of the public and what they expect their officers to understand and comply with at: https://www.met.police.uk/advice/advice-and-information/ph/photography-advice/

‘Freedom to photograph and film

Members of the public and the media do not need a permit to film or photograph in public places and police have no power to stop them filming or photographing incidents or police personnel.

Creating vantage points

When areas are cordoned off following an incident, creating a vantage point, if possible, where members of the media at the scene can see police activity, can help them do their job without interfering with a police operation. However, media may still report from areas accessible to the general public.

Identifying the media

Genuine members of the media carry identification, for instance the UK Press Card, which they will present on request.

The press and the public

If someone distressed or bereaved asks the police to stop the media recording them, the request can be passed on to the media, but not enforced.

Access to incident scenes

The Senior Investigating Officer is in charge of granting members of the media access to incident scenes. In the early stages of investigation, evidence gathering and forensic retrieval take priority over media access, but, where appropriate, access should be allowed as soon as is practicable.’

Review by Hertfordshire Police and Apologies to Journalists

Hertfordshire Police instituted an independent review of the arrests of journalists covering the Just Stop Oil protests which was carried out by the Cambridgeshire Constabulary. It concluded that the journalists should not have been arrested. The Chief Constable of Hertfordshire Police directly apologised to the arrested journalists.

M25 arrests review See: https://www.herts.police.uk/news/hertfordshire/news/2022/november/m25-arrests-review/

Chief Constable Charlie Hall said: ‘“Whilst the review has correctly concluded that the arrests of the journalists were not justified, and that changes in training and command need to be made, it found no evidence to indicate that officers acted maliciously or were deliberately disproportionate. They made mistakes and I now reiterate my apologies.’

As a result of the review Hertfordshire Police accepted five recommendations:

1.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider selecting commanders with commensurate skills and experience when balanced against the nature of the operation.

2.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider ensuring that mentors collate with commanders for the duration of the operation.

3.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider ensuring that all commanders have access to Public Order Safety (POPS) advisors.

4.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider affording commanders with the ability and capacity to maintain accurate decision logs.

5.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider ensuring that all officers engaged with public order activity complete the NUJ package and identified learning is shared.

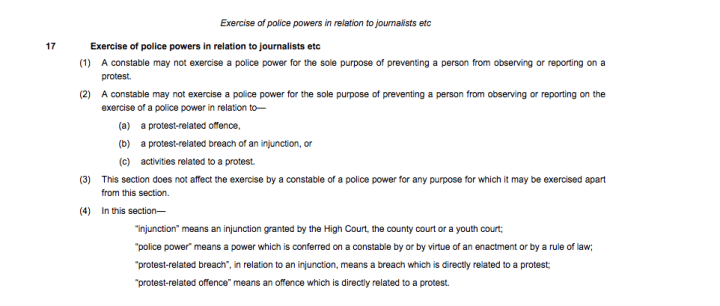

Legislative change to the new Public Order Act in 2023 to protect journalists from arrest when covering public protests

An amendment in the House of Lords to the Public Order Act 2023 passed on 7th February 2023 introduced statutory safeguards protecting journalists from arrest when observing or reporting on the type of protests carried out by climate change activists.

The aim has been to separate in law the professional work of journalists of merely being there to report from any suspicion or belief on the part of the police that by doing so they are conspiring or participating in ‘direct political action’ that is so disruptive as to amount to actual public order offences.

Section 17 under subsection (1) states the police may not use their powers ‘for the sole purpose of preventing a person from observing or reporting on a protest.’

Subsection (2) prevents the police from using their powers for the sole purpose of preventing a person from observing or reporting on the exercise of a police power in relation to:

(a) a protest-related offence,

(b) a protest-related breach of an injunction, or

(c) activities related to a protest.

These safeguards were proposed by the former director of Liberty and Labour peer Baroness Chakrabarti who explained that the amendment was designed to protect journalists, legal observers, academics and bystanders who might observe or report on protests or the police’s use of powers related to protests.

The amendment was approved by a majority of 283 to 192 and is expected to be brought into effect on 2nd July 2023.

Section 17 of the Public Order Act 2023

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/15/section/17

Press Gazette: ‘Protection for journalists added into anti-protest Public Order Bill. Campaigners had warned the Public Order Bill could make arrests of journalists “commonplace.”‘

See: https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/protection-for-journalists-added-into-public-order-bill/https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/protection-for-journalists-added-into-public-order-bill/

Some key journalists’ rights criteria when covering public news events.

1.Journalists have Article 10 freedom of expression and media rights under the European Convention of Human Rights and UK Human Rights Act (HRA) 1998 combined with English common law freedom of expression rights to cover news events without hindrance or interference from government authorities.

2.The National Press Card recognised by the National Police Chiefs’ Council should be a guarantee to any UK police officer that the holder is a legitimate professional journalist.

3.In the absence of this kind of card, any other identifying document or card from an employing organisation or association, even a commissioning letter/email from an editor, should be sufficient evidence of professional bone fide status.

4. Professional journalists never participate in protests and demonstrations and properly distinguish themselves from those people they are reporting on. This should be obvious to police officers. Everything should be done to avoid any ambiguity on this point. This is why the value of professional impartiality extends to a journalists’ personal social media and online presence.

5.Professional journalists have a right to cover news events using multimedia technology from public places and this is lawful behaviour. Privacy law issues should be a matter for the civil courts and not criminal police investigation.

6.Police officers should not ask journalists how and why they know protests or demonstrations are taking place. This is a prima facie interference with the Article 10 right to the protection of journalists’ sources.

7. Police officers need to have reasonable cause to suspect any journalist has committed an offence before proceeding to arrest, detention, and other processes such as taking DNA and photographs. If they do not, they face potential action for false arrest and unlawful imprisonment.

8. Police officers are obliged under the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act to perform reasonable steps when making any request of an individual in respect of an arrest or interruption of a working journalist. It is always useful for journalists or their colleagues to make notes, record/film the conduct and behaviour of the officer(s) though it is understandable why this might be difficult in some circumstances.

9. What should be done if police officers mistakenly arrest a journalist while lawfully covering a news event? It is advisable to politely ask the officers what their ‘reasonable suspicion’ amounts to. It is not advisable for journalists to resist the police officers physically in any situation. It might help to always make it clear that there is no intention to obstruct, or give actual interference with the police officers carrying out their duties. It might also help to try and stress the advantage of clarifying any misunderstanding; avoiding the waste, expense, cost, and paperwork of complaints and future litigation.

10.There is no harm in professional journalists reminding the police that they have been lawfully covering a public interest news event, they have properly identified themselves as such and the arrest is not reasonable or necessary in law. The circumstances and personalities of the arresting officers might be such that silence and not over-stating the issue could be the best strategy. There may be an advantage in suggesting that arresting police officers sought the advice of their senior officers and commanders in respect of their actions.

11. The police may have a power under the Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 (Section 19) to seize under lawful search digital reporting equipment with photographs, video and sound, but journalists are entitled to the protection under 1984 PACE that this material is protected as ‘special procedure material.’ The police must get a court order to search this material and only a Crown Court judge can issue a warrant. The police can seize equipment in order to ascertain whether or not the content is ‘special procedure material,’ but if the journalism equipment, smart phone, digital recording devices and SD cards, are labelled “Special Procedure Material collected for the purposes of journalism under PACE 1984” then the police can be in no doubt about their legal obligations.

12.There is further protection for ‘confidential journalistic’ material under the 1984 PACE legislation that effectively blocks police access, even with application for court orders, unless there is an investigation for a very serious indictable offence. When journalists collect information and media material subject to a journalistic confidentiality agreement it is advisable to label this as ‘Confidential Journalistic Records under 1984 PACE.’ However, journalists might have difficulty getting the courts to recognise the ‘confidential’ designation if they have been recording a public event because actions in public can be hardly evaluated as ‘confidential’- only the special procedure material protection applies. It can certainly be argued that a smartphone is likely to include confidential journalistic records and journalists would have a right to withhold the password accessing the device.

13. It would seem journalists and photographers had been arrested by Hertfordshire Police for alleged ‘conspiracy to commit a public nuisance.’ The professional journalistic coverage of a public interest news event is not a criminal nuisance. This includes photographing, digitally videoing and sound recording such an event. It can be argued that for such an arrest to be ‘reasonable’, the police would need to have evidence that journalists agreed to protest and disrupt with the activists. No professional journalists carrying out their impartial reporting duties would ever agree to such a course of action. It can be strongly argued that journalists receiving information from protest groups that ‘something is going to happen at such a time and in such a place’ does not amount to ‘conspiracy to commit a public nuisance.’ Such communications should have the shield of journalist source protection law under Article 10 Human Rights Law. Journalists have the right not to disclose anything about such communications.

14.Unfortunately the Investigatory Powers Act 2016 does give the police (and other state bodies) powers to access mobile, computer and digital communications information between journalist sources and journalists if they are investigating serious crime which is defined as any criminal offence with a minimum jail sentence of one year’s imprisonment. The oversight by the Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office (IPCO) and The Office for Communications Data Authorisations (OCDA) is done in secret by judicial commissioners and civil service with very limited accountability. If journalist communications have been intercepted and the connections made by the police, journalists have no right to know about this or even represent their position in any review by a judicial commissioner. Consequently, journalists should think carefully about the digital trails of their communications with sources.

15. Do journalists have any positive legal obligation to report prior knowledge of potential criminal behaviour to the police? At the moment there is only a positive duty under:

Section 38B(1) and (2) of the Terrorism Act 2000 which makes it an offence if someone does not inform the police if he/she believes that someone they know is in preparation of acts of terrorism. The maximum sentence in respect of Section 38B is for a term not exceeding five years’ imprisonment, although it is a defence to prove that he/she had reasonable excuse for not making the disclosure. Obviously the disruptive actions of Just Stop Oil protesters and environmental activists are not acts of terrorism. In any communications between journalists and their sources in protest groups, it is advisable to avoid receiving any information about the detail and nature of protests and events being planned. It is enough to receive information about time and place in order to avoid any potential ethical dilemmas generated by the nature of the full detail of prior knowledge offered.

16. Some self-evident observations:- professional journalists covering Just Stop Oil disruption can obviously do so in a lawful way from public places. It would not be lawful for them to join the activists on an M25 gantry. Similarly if a criminal fugitive who has escaped custody contacts a journalist and wants to provide an interview, this should only be done remotely. The journalist should not agree to meet the fugitive for an interview unless the fugitive agrees to surrender back into custody at the same time. There are obviously risk assessment and personal safety issues for the employing organisation to resolve with their journalist(s) beforehand.

17. Journalists need to be provided with effective identifying documentation, media cards and lanyards to demonstrate their bona fide status as journalists when covering public interest news events. If they have not been issued with a UK Press Card Authority card, they should be in possession of an accreditation letter from their editor and employing/commissioning news publisher with contact numbers and details for verification.

18. Some useful background case histories-

-o-

The wrongful arrest of two investigative journalists and the search of their homes by the police in Northern Ireland on behalf of the Durham Constabulary led to legal condemnation by the Northern Ireland High Court and the award of hundreds of thousands of pounds in damages. See Belfast Telegraph story in 2020: ‘Police to pay out millions after settling case over journalist arrests’ at: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/police-to-pay-out-millions-after-settling-case-over-journalist-arrests-39799447.html

And ‘Journalist gets police apology for arrest over Kent barracks photos. Force admits detention of Andy Aitchison after he covered protest at Napier barracks was unlawful.’ See Guardian story in October 2021: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/oct/22/journalist-gets-police-apology-for-arrest-over-kent-barracks-photos

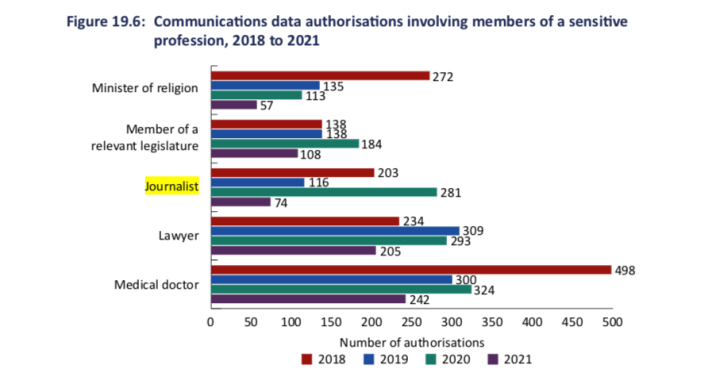

Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Report for 2021 reveals information on intercepting journalists’ communications with sources. 11th April 2023.

It also discloses the first example of a Judicial Commissioner refusing an application to access data relating to journalists and their sources.

It seems the scale/number of state interception of journalists’ communications is substantially down on previous years.

74 authorisations in 2021 compared to 281 in 2020.

The report, for the first time, provides some more detail on the circumstances of interception and identification of the nature of contact between journalist source and journalists.

However, the report does not identify the journalists concerned, the people they were talking to, or their publications.

Two clear examples of interception of data relates to police officers or police staff and journalists.

One case reveals the police were investigating information being leaked by a police officer to a freelance journalist for financial gain.

Another case reveals investigation of police staff for leaking information to journalists resulting in a victim being contacted. The misconduct in public office issue did not disclose this being done for financial gain.

The report reveals an instance where a Judicial Commissioner refused an application for interception of communications data between a source and journalist. The rejection of the application was due to the fact of ‘there being no evidence the allegations had been leaked, nor had they appeared in the public domain several weeks following the suspected leak.’ The information being sought was the ‘name of an officer who was facing a misconduct hearing.’ It is not clear whether the source was a police officer, police staff or somebody else.

The report says the News Media Association and Media Lawyers’ Association met with the IPCO Chief Commissioner Sir Brian Leveson to talk about improving the reporting of this information.

Annual Report of the Investigatory Powers Commissioner 2021 and the activities of the Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office (IPCO) and Office for Communications Data Authorisations (OCDA).

See: https://ipco-wpmedia-prod-s3.s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/Annual-Report-2021.pdf

The Appeal Court rules High Court can review bulk collection of journalists’ data by UK law enforcement in 2016 Investigatory Powers Act. But at the same time the review will not include use of other secret powers of surveillance in respect of journalists’ confidential information and sources. 30th August 2023.

In a ruling released on 4th August, three appeal court judges said the High Court should decide whether the act provides “adequate safeguards for the protection of a journalist’s sources or confidential journalistic material in relation to communications obtained by means of a bulk equipment interference warrant”.

See Summary in National Council for Civil Liberties -v- Secretary of State for the Home Department at: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/R-Liberty-v-Secretaries-of-State-Summmary-040823.pdf

Full detailed ruling (116 pages) at https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/R-Liberty-v-Secretaries-of-State-Judgment-040823.pdf

Paragraph 4 and 5 of the summary of the ruling explain the defeat for Liberty and National Union of Journalists on reviewing the provisions for accessing data communications about journalist’s confidential data and dealings with their sources:

‘4. The appellant contended that the 2016 Act did not provide adequate safeguards against the risk of abuse or for the protection of journalistic material and sources. In particular, the appellant contended that the 2016 Act did not, in a number of respects, meet the requirements outlined by the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights in its judgment in Big Brother Watch v United Kingdom which concerned the compatibility of provisions of a predecessor statute with Articles 8 and 10 of the Convention.

5. The Court of Appeal considered in detail the legal regimes governing each type of warrant. The Court concluded that, save in one respect, the provisions contained in the 2016 Act do provide adequate safeguards against the risk of abuse and protect confidential journalistic material and journalistic sources. The Court held that there are adequate safeguards providing for the sharing of information with authorities overseas but, in respect of one category of material (that is data obtained from bulk personal datasets) those safeguards are not in accordance with law, and so not compatible with Article 8 of the Convention, because the safeguards governing such transfers are not contained in any legislation, code or publicly available policy or other document. The Court of Appeal also remitted one issue to the Divisional Court for it to determine, namely whether the provisions contained in Part 6 Chapter 3 of the Act governing the grant of bulk equipment interference warrants authorising the interference with equipment for the purposes of obtaining communications and other data and information are sufficient to provide adequate safeguards for the protection of a journalist’s sources or confidential journalistic material. The Court also held that the provisions of the Act were compatible with retained EU law.’

Press Gazette reports 8th August 2023 ‘High Court to review bulk collection of journalists’ data by UK law enforcement.The High Court will re-examine journalistic safeguards in one part of the Investigatory Powers Act.’ See: https://pressgazette.co.uk/media_law/snoopers-charter-journalistic-safeguards-court-of-appeal/

PDF file on Snooper’s charter media law briefings

Highly significant European Court of Human Rights Grand Chamber ruling extending and strengthening Article 10 Protection of Journalists’ sources to the sources themselves when they act in the role of ‘good faith’ whistleblowers with public interest disclosure. Judgement in Strasbourg 14th February 2023 in the case of Halet v Luxembourg (Application no. 21884/18)

This is also known as the ‘Luxleaks case’ and was summarized and referenced on pages 161 to 162 of the printed 2022 Second Edition of UK Media Law Pocketbook.

Very briefly the case concerned Raphaël Halet, a French national, who worked for PricewaterhouseCoopers accountants in Luxembourg. The judges have ruled there was a violation of his whistle-blower’s freedom of expression, Article 10 rights as a result of his criminal conviction for disclosing confidential documents protected by professional secrecy, comprising 14 tax returns of multinational companies and two covering letters, obtained from his workplace.

He says he did this to a journalist in the public interest for no financial reward.

Up until now Article 10 protection of journalist source rights in Strasbourg cases have been robustly asserted in respect of the journalists, but this had not been clearly extended to the sources themselves when they suffered consequences from their exposure or identification.

In Monsieur Halet’s case, he had been criminally prosecuted and fined 1,000 Euros and additionally ordered to pay 1 Euro in compensation.

The Grand Chamber ruling is summarized with the following bullet-points:

Art 10 • Freedom of expression • Criminal-law fine of EUR 1,000 for disclosing to the media confidential documents from a private-sector employer concerning the tax practices of multinational companies (Luxleaks) • Consolidation of the European Court’s previous case-law on the protection of whistle-blowers and fine-tuning of the criteria established in the Guja judgment • No abstract and general definition of the concept of whistle-blower • Claim for protection under this status to be granted depending on the circumstances and context of each case • Overall assessment by the Court of the Guja criteria, taken separately, but without hierarchy or specific order • Channel selected to make the disclosure was acceptable in the absence of illegal conduct by the employer • Authenticity of the disclosed documents • The applicant’s good faith • Necessary balancing of competing interests at stake by the Grand Chamber, as the domestic courts’ balancing exercise did not satisfy the requirements identified in the present judgment • Overly restrictive interpretation of the public interest of the disclosed information, which had made an essential contribution to a pre-existing debate of national and European importance • Only the detriment caused to the employer taken into account by the domestic courts • Public interest in the disclosure outweighed all of the detrimental effects, including the theft of data, the breach of professional secrecy and the harm to the private interests of the employer’s customers • Disproportionate nature of the criminal conviction.

See the full ruling of the court https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-223259%22]}

PDF document also available on this link

The legal summary of the case is available on this link: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22002-14005%22]}

The press release about the ruling is available on the link below:

This is not an all-encompassing template offering a strong pre-determined legal shield for journalists’ sources disclosing confidential information to journalists during their employment, but it will be influential and the seed for developing important precedents in this area.

It may strengthen the position of civil servant ‘whistle-blowers’ communicating to journalists public interest information without any financial reward or favour who under current English and Welsh criminal law face prosecution for misconduct in public office.

The judges explained there is no abstract and general definition of the concept of whistle-blower and the claim for protection under this status is to be granted depending on the circumstances and context of each case.

The ruling derived from principles developed in the 2008 Grand Chamber ruling of Guja v. Moldova which ‘had identified for the first time the review criteria for assessing whether and to what extent an individual divulging confidential information obtained in his or her workplace could rely on the protection of Article 10 of the Convention, and specified the circumstances in which the sanctions imposed were such as to interfere with the right to freedom of expression.’

The Grand Chamber judges in Halet decided that the context for whistleblowers had changed since 2008 ‘whether in terms of the place now occupied by whistle‑blowers in democratic societies and the leading role they were liable to play by bringing to light information that was in the public interest, or in terms of the development of the European and international legal framework for their protection.’

Halet is therefore important in confirming and consolitating the principles established in case-law for the protection of whistle‑blowers by refining the six criteria for their implementation:-

(1) The channels used to make the disclosure; (2) The authenticity of the disclosed information; 3) Good faith; (4) The public interest in the disclosed information; (5) The detriment caused, and (6) The severity of the sanction.

The Grand Chamber in Halet ‘verified compliance with the various Guja criteria taken separately, without establishing a hierarchy between them or indicating the order in which they were to be examined, which, while it had varied from one case to another, had never an impact on the outcome of the case. However, in view of their interdependence, it was after undertaking a global analysis of all these criteria that it ruled on the proportionality of an interference.’

The majority of 12 to 5 ruled that the interference with the Monsieur Halet’s right to freedom of expression by criminal prosecution, conviction and fine, in particular his freedom to impart information, had not been ‘necessary in a democratic society.’

The ruling has been welcomed by Protect the UK’s whistle-blowing charity ‘European Court backs LuxLeaks Whistleblower in his decision to expose tax avoidance in the public interest.’ See: https://protect-advice.org.uk/protect-luxleaks-whistleblower/

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists was involved in reporting the Luxleaks case and reported the Grand Chamber ruling: ‘European court reverses course to rule in favor of LuxLeaks whistleblower. The European Court of Human Rights ruled that the public interest in leaking the data showing how multinationals spirited profits to the tiny nation outweighed the detrimental effect.’

Stelios Andreadakis, Reader in Corporate and Financial Law at Brunel University London, and Dimitrios Kafteranis Assistant Professor at the Centre for Financial and Corporate Integrity, Coventry University observed in their article for the Oxford Business Law Blog: ‘Apart from the undeniable impact of the judgment in relation to the right to freedom of expression, reference should be made to the notable protection offered to a whistleblower, who wanted to do the right thing, in good faith and without any intention to profit from it or to harm his employer. If the original criminal conviction had a ‘chilling effect’ on potential whistleblowers, who were considering speaking out about wrongdoings in their workplace, the Grand Chamber’s decision was a step towards the right direction: the direction of transparency, accountability and fairness.’

See: ‘Halet v Luxembourg: The Final Act of the Luxleaks Saga’ at: https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/blog-post/2023/02/halet-v-luxembourg-final-act-luxleaks-saga

On 27th July 2023 a key member of the Royal Family lost part of an action in media law against a UK national newspaper organisation, which is something of a rare phenomenon. The Duke of Sussex, more commonly known as ‘Prince Harry’ was unsuccessful is pursuing litigation on phone hacking against News Group Newspapers, the publishers of the Sun newspaper.

However, the judge did find in favour of the claimant in being able to pursue an action for misuse of private information through unlawful information gathering such as use of private investigators.

The action against News Group Newspapers/Sun is part of a portfolio of litigation by the Duke of Sussex.

He departed from Royal Family convention in June 2023 when he became the first senior member of the royal family to testify in court in more than a century.

He testified in a separate phone hacking lawsuit against the publishers of the Reach/Daily Mirror in which he is seeking 440,000 pounds ($563,000).

The same judge, Mr Justice Fancourt also presided in that case, the first of the Duke of Sussex’s three unlawful information gathering cases against British tabloid publishers to go to trial. The judge is expected to rule on this issue later this year.

Another judge is deciding on a similar lawsuit against the publishers of the Associated Newspapers/Daily Mail.

See the summary of Mr Justice Fancourt’s ruling 27th July 2023 at: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Duke-of-Sussex-v-NGN-summary-270723.pdf

The full ruling (40 pages) is available to download at: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Duke-of-Sussex-v-NGN-Judgment-270723.pdf

British and Irish Legal Information Institute online hosting of full judgment at:

Duke of Sussex v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2023] EWHC 1944 (Ch) (27 July 2023)

There has been an apparent contrast in the way the Guardian and BBC reported the outcome compared with the Mail Online and Telegraph:

See examples of the different journalism reports:

Guardian: ‘Prince Harry’s lawsuit against Sun publisher can go to trial, judge rules.High court rules prince’s claims of illegal information gathering can proceed but phone-hacking allegations cannot.’ See: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/jul/27/prince-harrys-lawsuit-against-sun-publisher-can-go-trial-judge-rules

BBC News: ‘Prince Harry set for court showdown with The Sun publisher. The Duke of Sussex is to take The Sun’s publisher to court over claims it used illegal methods to gather information on him.’ See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-66322279

Mail Online: ‘Prince Harry’s phone hacking case against The Sun’s publisher and claim of ‘secret agreement’ between Buckingham Palace and the Press is thrown out by a judge – but other claims against paper will go to trial.’ See: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12343855/Prince-Harrys-phone-hacking-case-against-Suns-publisher-thrown-judge-claims-against-paper-trial.html

Telegraph (behind paywall): ‘Prince Harry’s phone hacking claim against Sun publisher thrown out by judge. Only part of the Duke of Sussex’s lawsuit will now go to trial at the High Court, which is due to begin in January next year.’ See: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/royal-family/2023/07/27/prince-harry-sun-publisher-lawsuit-trial/

This case was about a motion by News Group Newspapers to have all of the Duke’s claims struck out with summary ruling in their favour on the grounds they were out of time because his claims were made beyond the six year limit for civil litigation under the 1980 Limitation Act.

Between paragraphs 7 to 11 of the summary of his ruling, Mr Justice Fancourt explains why the Duke cannot amend his claim and the phone hacking case will be struck out:

‘7. The Duke’s original pleaded case was that he was unaware until about 2018 that he had a claim to bring, save in relation to one isolated occasion of phone-hacking in 2006.

8. In March 2023, the Duke made a witness statement explaining that there was a secret agreement, which he said required him only to bring a claim against News Group at a much later time, when it would be admitted by News Group or settled with an apology. He said that he did not bring his claim in about 2012 because he relied on this secret agreement.

9. The Duke only made an application to amend his pleaded case to rely on the secret agreement during the hearing of News Group’s application, in April 2023.

10. The Duke’s proposed amended case did not reach the necessary threshold of plausibility and cogency for permission to be granted to amend his case at this stage. There was no witness or documentary evidence to support what the Duke claimed. It raised for the first time a case that was inconsistent with the existing pleaded case. Despite the attempts of the Duke’s lawyers to enable both cases to proceed, the attempt to do so failed.

11. Accordingly, permission to amend the Duke’s pleaded case was refused.’

The judge goes onto say at paragraphs 16 and 17 the trial of the other allegations of unlawful gathering of personal information will proceed:

‘16. In relation to the other Unlawful Acts, however, the decision is that the Duke has a realistically arguable case at trial that he did not by 27 September 2013 know (and could not reasonably have found out) enough about blagging of his confidential information and the commissioning of private investigators to do other alleged Unlawful Acts, to believe then that he had a worthwhile claim.

17. Whether the Duke issued his claim for these other Unlawful Acts too late is one of the many issues in the claim that will have to be decided at trial, in 2024 or 2025. The judgment does not decide that the Duke’s claim in respect of them was issued in time: it only decides that it is not sufficiently clear at this stage that it was issued too late.’

In the full ruling Mr Justice Fancourt deals with his view of the Duke’s evidence at paragraph 75:

‘The evidence in support of the pleaded case is limited to that of the Duke. It is not strong evidence. The Duke is unable to identify between whom the secret agreement was made, or even who it was who told him about it. His case is that it might have been Gerrard Tyrrell, a solicitor at Harbottle & Lewis who acted for the Royal Family, or it might have been “someone else at the Institution”. The originally pleaded case was that the Duke became aware through legal advisers to his family in about 2018 that he could bring a claim against NGN; but by the intended amendment, that is to be changed to his becoming aware that he could bring a claim in 2017 after permission was given by The Queen. Given that Gerrard Tyrrell was acting on behalf of the Duke in 2012 – in connection with phone hacking and another matter – one might have expected to see some evidence from Mr Tyrrell, or from Ms Osman or Sir Christopher Geidt, giving support to the Duke’s factual case, but there is none.’

At paragraph 82 the judge observe: ‘…the problem with the Duke’s pleaded case is that there is nothing other than his rather vague and limited evidence to support it: there is no documentary evidence that supports a case about 2012 and his reliance; there is no evidence from those acting for the Royal Family at the time who might have been expected to support his account, if it is correct; and his own previously pleaded case and evidence in other cases are inconsistent with it.’

And at paragraph 91 the judge rules:

‘For all the reasons that I have given, I am unable to conclude that there is a sufficiently plausible evidential basis for the new case based on the secret agreement to justify the grant of permission to amend at a late stage of the proceedings. The lack of credibility arises from: the unexplained lateness of the plea, linked to the nature of the estoppel plea; the improbability of a secret agreement being made in the particular terms pleaded; the inconsistency with the Duke’s currently pleaded case, which is twice supported by statements of truth, and with his evidence in other proceedings, supported by a statement of truth; the absence of any explanation for the new factual case being raised; and the absence of any other witness or documentary evidence to support it.’

Clearly are there further significant hearings to take place and rulings to be made in the campaign of media law litigation being run by the Duke of Sussex against the News Group, Associated Press and Reach newspaper groups and I will do my best to cover them in future years.

PDF file media law briefing on this case:

Secondary Media Law Codes and Guidelines

IPSO Editors’ Code of Practice in one page pdf document format https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2032/ecop-2021-ipso-version-pdf.pdf

The Editors’ Codebook 144 pages pdf booklet 2023 edition https://www.editorscode.org.uk/downloads/codebook/codebook-2023.pdf

IMPRESS Standards Guidance and Code 72 page 2023 edition https://www.impress.press/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Impress-Standards-Code.pdf

Ofcom Broadcasting Code Applicable from 1st January 2021 https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code Guidance briefings at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/information-for-industry/guidance/programme-guidance

BBC Editorial Guidelines 2019 edition 220 page pdf http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/guidelines/editorialguidelines/pdfs/bbc-editorial-guidelines-whole-document.pdf Online https://www.bbc.com/editorialguidelines/guidelines

Office of Information Commissioner (ICO) Data Protection and Journalism Code of Practice 2023 41 page pdf https://ico.org.uk/media/for-organisations/documents/4025760/data-protection-and-journalism-code-202307.pd and the accompanying reference notes or guidance 47 page pdf https://ico.org.uk/media/for-organisations/documents/4025761/data-protection-and-journalism-code-reference-notes-202307.pdf