THE UK MEDIA LAW POCKETBOOK

by Tim Crook

Published by Routledge 30th November 2022

Chapter 6

Copyright and Intellectual Property

Explaining the nature of UK copyright law for media communicators and concentrating on the defence of ‘fair dealing.’

Responsibility in terms of sourcing and clearing text, images, design and tables. Understanding the distinction of fair dealing between reporting current events and criticism or review.

Fair dealing no defence for using in copyright images when reporting current events and its limitations in relation to criticism and review.

Duration of copyright. Issues in relation to online and Internet technology and application of copyright law in social media and new digital platforms.

Copyright in relation to artwork, public sculpture and exhibitions.

If you are reading and accessing this publication as an e-book such as on the VitalSource platform, please be advised that it is Routledge policy for clickthrough to reach the home page only. However, copying and pasting the url into the address bar of a separate page on your browser usually reaches the full YouTube, Soundcloud and online links.

The companion website pages will contain all of the printed and e-book’s links with accurate click-through and copy and paste properties. Best endeavours will be made to audit, correct and update the links every six months.

Video-cast on Copyright and Intellectual Property Law

6.0 Five key bullet points summarizing UK copyright for media publishers

A downloadable sound file vocalizing bullet points on British intellectual property law

6.1 Explaining UK copyright and fair dealing

A downloadable sound file summarizing the principles of UK copyright and ‘fair dealing’

Online Links Printed Book

Pages 187 and 188

1988 Copyright Designs and Patents Act

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents

HRH The Duchess of Sussex v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2021] EWHC 273 (Ch) (11 February 2021) (paragraphs 130 to 169 relevant to the copyright claim)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2021/273.html

HRH the Duchess of Sussex v Associated Newspapers Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 1810 (02 December 2021)

https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2021/1810.html

Baigent & Anor v The Random House Group Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 247 (28 March 2007)

https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/markup.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2007/247.html

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, Chapter IV Moral Rights- Right to be identified as author or director

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/part/I/chapter/IV

UK government’s Intellectual Property Office

https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/intellectual-property-office

One IPO Transformation Prospectus 2021- a five-year programme to transform intellectual property services and enhance the value IPO adds to the UK economy.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/one-ipo-transformation-prospectus

FACT- formed in 1983 to protect the content, product and interests of the film and television industries.

https://www.fact-uk.org.uk/

6.2 Fair dealing defence in detail and understanding its exclusion from photographs

Online Links Printed Book

Pages 190 and 192

Pro Sieben Media A.G. v Carlton Television Ltd & Anor [1998] EWCA Civ 2001 (17 December 1998)

https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/1998/2001.html

Time Warner Entertainments v Channel Four Television from 1993 (The Clockwork Orange case)

https://www.5rb.com/case/time-warner-v-channel-4-television/

Fraser-Woodward Ltd v British Broadcasting Corporation Brighter Pictures Ltd [2005] EWHC 472 (Ch) (23 March 2005)

https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/markup.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2005/472.html

IPC Media Ltd v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2005] EWHC 317 (Ch) (24 February 2005)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2005/317.html

Ashdown v Telegraph Group Ltd [2001] EWCA Civ 1142 (18 July 2001)

http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2001/1142.html

Hyde Park Residence Ltd v Yelland & Ors [2000] EWCA Civ 37 (10 February 2000)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2000/37.html

England And Wales Cricket Board Ltd & Anor v Tixdaq Ltd & Anor [2016] EWHC 575 (Ch) (18 March 2016)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2016/575.html

The Copyright and Rights in Performances (Quotation and Parody) Regulations 2014 No. 2356

https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/uk/legis/num_reg/2014/uksi_20142356_en_1.html

6.3 Copyright duration and multiple copyright interests in media productions

6.4 Social media and news digital platforms

A downloadable sound file briefly summarizing copyright issues in relation to social media

Online Links Printed Book

Page 193

Press Gazette 26 January 2021 ‘Taking photos from social media: What news publishers need to know’

https://www.pressgazette.co.uk/taking-photos-from-social-media-copyright-publishers-guide/

VG Bild-Kunst (Intellectual property – Concept of ‘communication to the public’ – Embedding, in a third party’s website – Opinion) [2020] EUECJ C-392/19_O (10 September 2020)

https://www.bailii.org/eu/cases/EUECJ/2021/C39219_O.html

Getty Images: Site terms of use

https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/company/terms

Unsplash- Photos for everyone. License

https://unsplash.com/license

6.5 Artwork, public sculpture, exhibitions and incidental

6.6 Updates and stop press

A downloadable sound file updating on key developments in UK copyright and intellectual property law

Orphan works- a special licensing system managed by the UK Intellectual Property Office

One of the longstanding challenges to media publishers and journalists in copyright had been the issue of orphan works- these can be any kind of copyright material, primary and secondary, which has no apparent authorship.

This has been met by reform of the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act in 2014- ‘The Copyright and Rights in Performances (Certain Permitted Uses of Orphan Works) Regulations 2014’

These measures effectively implemented European Union law on orphan works with the explanatory note requiring the provision of ‘permitted uses of orphan works by relevant bodies.’

The Regulations necessitated ‘a diligent search, for the purpose of establishing whether a relevant work is an orphan work, and include a list of the minimum sources to be searched in different cases.’

The IPO set up the UK’s Orphan works licensing scheme and there is an eight page guidance briefing for right holders.

The IPO have also produced a YouTube video on the operation of the scheme.

The IPO explains:-

1.An orphan work is a copyright work where the right holder is unknown or cannot be located. The orphan works licensing scheme allows the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) to grant an applicant a non-exclusive licence to use an orphan work.

2.The scheme was launched on 29 October 2014 when the Copyright and Rights in Performances (Licensing of Orphan Works) Regulations 2014 came into force. An applicant must conduct a diligent search for the right holders in the work and submit details of that search to us as part of their application.

3.The purpose of the diligent search is to find right holders where they can be found and to demonstrate that all reasonable efforts have been taken where they cannot be found.

Orphan works online diligent search guidance. See: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/orphan-works-diligent-search-guidance-for-applicants/orphan-works-diligent-search-guidance

The IPO has provided diligent search guides with samples for copyright categories:-

Orphan works sample diligent search: photograph

Orphan works sample diligent search: unpublished literary work

Orphan works sample diligent search: printed music

Orphan works sample diligent search: film footage (production level)

Orphan works licensing scheme diligent search checklist: still visual art

Orphan works licensing scheme diligent search checklist: literary works

Orphan works licensing scheme diligent search checklist: film, music and sound

After licensing the IPO maintains an online register of orphan works- The orphan works register

The register is currently set out in six categories:-

The application for licensing operates online via the following link: Applying online to license an orphan work

High Court Copyright ruling 28th October 2022- Pasternak v Prescott [2022] EWHC 2695 (Ch)

The 492 paragraph ruling by Mr Justice Edwin Johnson. See: https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2022/2695.html

Key sections:-

The Judge’s summary of the case- paragraphs 2 to 6.

2.The Claimant, Anna Pasternak, is the author of the book Lara: The Untold Love Story That Inspired Doctor Zhivago (“Lara”). It was published in the United Kingdom on 25th August 2016. Lara is a non-fictional, historical work. It tells the story of the love affair of Boris Pasternak, poet and author of the world famous novel Doctor Zhivago, and the woman variously described as his lover, mistress and muse, Olga Ivinskaya. The Claimant is the great niece of Boris Pasternak. As the author of Lara, the Claimant is the owner of the copyright subsisting therein.

3.The Claimant also owns the copyright subsisting in the English translation of certain parts of a work entitled Légendes de la rue Potapov. The translation, from French to English, was the work of Marlene Hervey, who was commissioned to make the translation by the Claimant. Légendes de la Rue Potapov is the title of the French translation of a book written in Russian by Irina Kosovoi (nee Emelianova), daughter of Olga Ivinskaya. The actual Russian title, transliterated from the Cyrillic script, is Legendy Potapovskogo pereulka. No English edition of this book exists. It is convenient to refer to the English translation, in which the Claimant owns (by assignment) the subsisting copyright, as “the Legendes Translation”, while referring to the book itself as “Legendes”.

4.The Defendant, Lara Prescott, is the author of the book The Secrets We Kept (“TSWK”). It was published in the United States on 3rd September 2019 and in the United Kingdom on 5th September 2019. TSWK is a work of historical fiction. It is a fictionalised account of a CIA operation in the late 1950s, during the Cold War, to infiltrate copies of Doctor Zhivago into the Soviet Union as a propaganda weapon. The story is told in alternating parts, described as West and East, which effectively divide the story into two narrative threads. In the West chapters, the story is primarily told by and from the perspectives of a group of female typists and spies working for the CIA. In the East chapters, the story is primarily told by and from the perspective of Olga Ivinskaya.

5.The Claimant’s case is that 7 of the 11 chapters in the East section of TSWK infringe the copyright subsisting in 7 of the 12 chapters of Lara. The essential complaint is that the Defendant has copied, from the relevant chapters in Lara, a substantial part of the selection, structure and arrangement of facts and incidents which the Claimant is said to have created when she wrote Lara. The Claimant’s case is also that the Defendant has infringed the copyright in the Legendes Translation, in this case by the simple (language) copying, from Lara, of an extract from the Legendes Translation which is quoted in Lara.

6.The Defendant denies that she has, in TSWK, infringed the copyright in either Lara or the Legendes Translation.

Judge’s decisions. Paragraphs 406 to 412 on the ‘selection issue’- ‘copying from the relevant chapters in Lara, a substantial part of the selection, structure and arrangement of facts and incidents which the Claimant is said to have created when she wrote Lara.’

‘406. The way in which the Selection Claim has been formulated and pursued has required me to go through the individual allegations of copying, both in relation to the selection of Events and in relation to the Supporting Allegations, on a chapter by chapter basis. In the course of this lengthy exercise, I have stated my conclusions on the same chapter by chapter basis. The overall result of this exercise is that the Selection Claim fails, in relation to each of the chapters of Lara which is said to have been the subject of copying of selection.

407.It is however important to stress that I reach the same result by adopting the shorter route of considering, as a whole, all of the material which is said to have been the subject of copying of selection. If one stands back, and takes the relevant chapters of Lara as a whole, I do not think that this changes the evidential position; namely that it is clear that the Defendant did not copy from Lara the selection of events in the relevant chapters of TSWK or any part of that selection.

408.The essential reason for this is that Lara and TSWK are fundamentally different works. Lara is a non-fictional historical work. The Claimant stressed in her evidence that while it was her object to tell the story in an accessible and readable manner, reading more like fiction, the book is not a work of fiction and describes actual events. TSWK is a work of historical fiction. It is based on real events, but those real events have been woven into the story devised by the Defendant, and have themselves been adapted to suit the story. TSWK has been described as a spy thriller. I am not sure that this is quite how I would describe the book, but this description does bring out the essential difference with Lara; namely that TSWK is a work of fiction, loosely based on real events. This fundamental difference between the two works is apparent on a first reading of the two works.

409.Beyond this, and as will have been apparent from the detailed analyses set out in the previous sections of this judgment, the two works are written in very different styles, with different content and different arrangement.

410.A comparison between the two works, taken as a whole, is not of course the relevant comparison in the present case, where the Selection Claim is confined to certain chapters of Lara and certain chapters of TSWK. The differences in style, content and arrangement which I have identified are however equally apparent if one concentrates on the chapters of each work which are the subject of the Selection Claim.

411.The relevant chapters of each work are of course concerned with the same basic historical events in the lives of Boris and Olga. Both authors were using the same principal source materials; namely ACOT and TZA. The Defendant, on her own evidence, did use Lara as a secondary source. In these circumstances it is not surprising that the sequence of events, in each work, follows the same basic chronology, although I stress the reference to basic chronology; given the differences in events and their ordering as between the two works. Equally, it is not surprising that one finds some of the same details in each work. None of these areas of similarity or overlap seem to me to come anywhere near establishing that the Defendant copied the selection of events in the relevant chapters of Lara, or any part of that selection. This is so whether one considers the Selection Claim on a chapter by chapter basis, or as a whole. The evidence demonstrates that the Defendant took no more from Lara than odd details which, quite correctly, are not said to have been protected by copyright.

412.The Selection Claim – overall conclusions:

For the reasons which I have set out, the Selection Claim fails. The Defendant has not infringed the Claimant’s copyright in Lara in all or any of the ways alleged in the Selection Claim. Accordingly, the Selection Claim falls to be dismissed.

The Translation Claim. Paragraph 489

‘489. In any event the conclusion which follows from my discussion of the Translation Claim is that the Defendant has infringed the copyright in the translation of the Accusation Act which appears in the Legendes Translation. I have decided that copyright does subsist in the translation of the Accusation Act in the Legendes Translation. It is not in dispute that the Claimant took a valid assignment of that copyright. It is not in dispute that the Defendant did indirectly copy the translation of the Accusation Act, by her use of the quotation which she took from Lara. I have decided that the Defendant cannot rely upon the defence in Section 30(1ZA). Accordingly, the Translation Claim succeeds.’

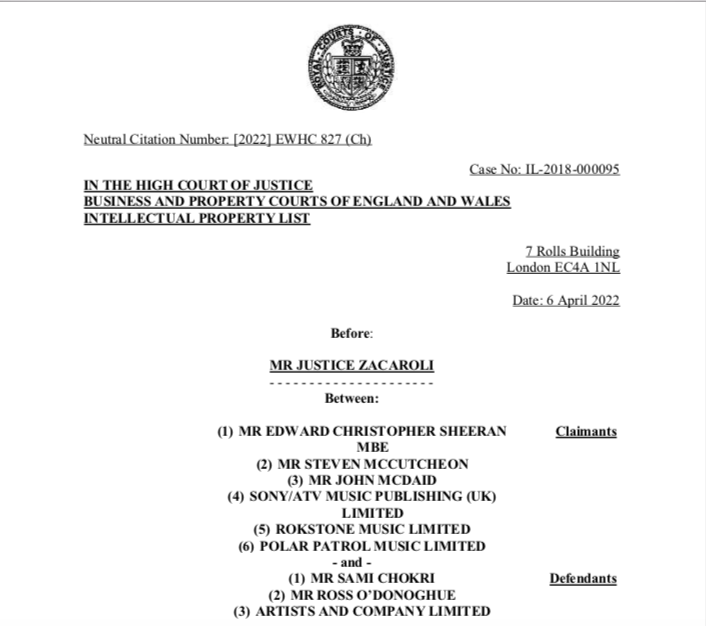

High Court Copyrights ruling 6th April 2022- Sheeran & Ors v Chokri & Ors [2022] EWHC 827 (Ch)

221 paragraph ruling by Mr Justice Zacarole. See: https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWHC/Ch/2022/827.html

The Judge’s summary of the case- paragraphs 1 to 6:

‘1.The first three claimants, Ed Sheeran, Steven McCutcheon and John McDaid are the writers of the song “Shape of You” (“Shape”). Shape, performed by Mr Sheeran, was released as a single on 6 January 2017 and included on Mr Sheeran’s album “÷” (“Divide”), released on 3 March 2017. It became the best-selling digital song worldwide in 2017. In December 2021 it became the first song to pass 3 billion streams on the streaming service Spotify. It has had more than 5.6 billion views on YouTube.

2.The first two defendants, Sami Chokri (who performs under the name Sami Switch) and Ross O’Donoghue, are the writers of the song “Oh Why”. The song was performed by Mr Chokri, released in mid-March 2015 and included on Mr Chokri’s EP “Solace”, released on 1 June 2015.

3.The fourth to sixth claimants are music publishing companies that own a share of the rights in the musical and literary works subsisting in Shape. The third defendant (“A&C”) is a music artists’ development, management and social media company and is the assignee of Mr Chokri’s copyright in Oh Why.

4.The defendants’ claim relates only to an eight-bar post-chorus section of Shape, in which the phrase “Oh I” is sung, three times, to the tune of the first four notes of the rising minor pentatonic scale commencing on C#. The defendants refer to this as a “hook”, commonly understood to mean that part of a song that stands out as catchy, memorable and keeps recurring. The claimants point out that there are other parts of Shape which are just as catchy, memorable and recur much more, for example the four-bar marimba pattern which starts the song and repeats throughout most of it, or the sung phrase “I’m in love with the shape of you” which defines the song. I will refer to the post-chorus passage in issue, neutrally, as the “OI Phrase”.

5.The defendants contend that the OI Phrase is copied from the eight-bar chorus of Oh Why, in which the phrase “Oh why” is repeated to the tune of the first four notes of the rising minor pentatonic scale, commencing on F#. This catchy and memorable phrase is clearly central to the song Oh Why, and I will refer to it as the “OW Hook”.

6.These proceedings were commenced by the first four claimants (and three other entities that were later replaced by the fifth and sixth claimants) on 16 May 2018, seeking declarations that they had not infringed copyright in Oh Why. The claim was issued following the defendants having notified the Performing Rights Society Limited (“PRS”) of their contention that they should be credited as songwriters of Shape, causing the PRS to suspend all payments to the claimants in respect of the public performance/broadcast of Shape. By a counterclaim, the defendants assert their claim that copyright in Oh Why has been infringed by the claimants.’

Key conclusions by the Judge at paragraph 205:

‘(1) While there are similarities between the OW Hook and the OI Phrase, there are also significant differences;

(2) As to the elements that are similar, my analysis of the musical elements of Shape more broadly, of the writing process and the evolution of the OI Phrase is that these provide compelling evidence that the OI Phrase originated from sources other than Oh Why;

(3) The totality of the evidence relating to access by Mr Sheeran to Oh Why (whether by it being shared with him by others or by him finding it himself) provides no more than a speculative foundation for Mr Sheeran having heard Oh Why;

(4) Taking into account the above matters, I conclude that Mr Sheeran had not heard Oh Why and in any event that he did not deliberately copy the OI Phrase from the OW Hook;

(5) While I do not need to resort to determining where the burden of proof lies, for completeness:

(a) the evidence of similarities and access is insufficient to shift the evidential burden so far as deliberate copying is concerned to the claimants;

(b) the defendants have failed to satisfy the burden of establishing that Mr Sheeran copied the OI Phrase from the OW Hook; and

(c) even if the evidential burden had shifted to the claimants, they have established that Mr Sheeran did not deliberately copy the OI Phrase from the OW Hook.

(6) Finally, again taking into account all the matters I have considered above, I am satisfied that Mr Sheeran did not subconsciously copy Oh Why in creating Shape.’

Secondary Media Law Codes and Guidelines

IPSO Editors’ Code of Practice in one page pdf document format https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2032/ecop-2021-ipso-version-pdf.pdf

The Editors’ Codebook 144 pages pdf booklet 2023 edition https://www.editorscode.org.uk/downloads/codebook/codebook-2023.pdf

IMPRESS Standards Guidance and Code 72 page 2023 edition https://www.impress.press/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Impress-Standards-Code.pdf

Ofcom Broadcasting Code Applicable from 1st January 2021 https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/broadcast-codes/broadcast-code Guidance briefings at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/tv-radio-and-on-demand/information-for-industry/guidance/programme-guidance

BBC Editorial Guidelines 2019 edition 220 page pdf http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/guidelines/editorialguidelines/pdfs/bbc-editorial-guidelines-whole-document.pdf Online https://www.bbc.com/editorialguidelines/guidelines

Office of Information Commissioner (ICO) Data Protection and Journalism Code of Practice 2023 41 page pdf https://ico.org.uk/media/for-organisations/documents/4025760/data-protection-and-journalism-code-202307.pdf and the accompanying reference notes or guidance 47 page pdf https://ico.org.uk/media/for-organisations/documents/4025761/data-protection-and-journalism-code-reference-notes-202307.pdf