UK Media Law Pocketbook Second Edition 30th November 2022

By Tim Crook

Online chapter

In addition to the separate legal jurisdictions of England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, the self-governing British Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands also have their own separate legal jurisdictions.

Consequently, they have their own bodies of media law.

This online chapter summarizes the position of libel, media contempt, privacy and other restrictions engaged in these island territories of the British Isles which are neither part of the United Kingdom nor the European Union.

The content and multimedia resources for this online chapter are under continuing construction and development.

If you are reading and accessing this publication as an e-book such as on the VitalSource platform, please be advised that it is Routledge policy for clickthrough to reach the home page only. However, copying and pasting the url into the address bar of a separate page on your browser usually reaches the full YouTube, Soundcloud and online links.

The companion website pages will contain all of the printed and e-book’s links with accurate click-through and copy and paste properties. Best endeavours will be made to audit, correct and update the links every six months.

Constitutional Geography and overview of British Island legal systems

- The Isle of Man and Channel Islands are not part of the United Kingdom and have never been part of the European Union. They are self-governing UK Crown Dependencies, with their own legal systems and constitutions- the UK has responsibility for their defence and representation abroad. They have their own systems of primary and secondary media law which are similar to the UK, but with some distinctive differences;

- The Isle of Man is an island in the Irish Sea situated between the north of England and east coast of Ireland and in its own 2021 census recorded a population of 84,069 people. 26,677 live in the island’s capital, Douglas. The Channel Islands consist of an archipelago in the English Channel situated off the French coast of Normandy. Geographically they are closer to France than Britain. Sometimes a distinction is made between the Channel Islands being considered part of the British Islands because of their close geographical proximity to France, and the Isle of Man being part of the British Isles;

- The Channel Islands include two Crown Dependencies- the Bailiwick of Jersey, which is the largest of the islands; and the Bailiwick of Guernsey, consisting of Guernsey, Alderney, Sark, Herm and some smaller islands. The total population on the archipelogo is about 171,916. The two Bailiwicks are separate self-governing entities with their own legal jurisdictions. And to complicate matters the Bailiwick of Guernsey is divided into three jurisdictions – Guernsey, Alderney and Sark – each with its own legislature;

- If you are a media publisher intending to despatch journalists to cover legal stories in these territories I would advise hiring the freelance consultation and guidance of experienced local journalists trained and familiar with local law and culture. If issues of media law liability arise it is also essential to instruct members of the legal profession qualified to practice in the law of these jurisdictions;

Tradition and legacy of freedom of the press on the Isle of Man

- These islands have distinguished and noble traditions of journalistic independence. For example, The Isle of Man Daily Times showed impressive defiance in the face of a threat of libel action on 1st August 1907 in this editorial: ‘We published in our issue of Saturday last some matter contributed by a correspondent of ours who writes under the head of “Chats.” This matter contained paragraphs severely stigmatizing a firm known as the “Norris-Meyer Press” for publishing a filthy postcard. We have since received a letter from Mr. R.D. Farrant acting under instructions from the firm in question, threatening us with an action for libel in respect of the comments of our correspondent, published by us above stated, unless we insert what is described as a “properly-worded apology” and retraction in our next issue in a “prominent place.” In view of the nature of the postcard referred to by our correspondent, we consider the sending of this letter to us a piece of intolerable insolence and effrontery. So far from apologising or retracting, we now reiterate and lay emphasis on very word used by our correspondent; and we shall be prepared to meet any action for libel in connection with the subject’;

- This is an early historical example of resistance to what is now recognised as ‘lawfare’ against journalists or SLAPPs- standing for strategic lawsuits against public participation whereby lawyers act for usually rich and powerful people and organisations to suppress and intimidate journalism published in the public interest which is critical of and questioning their behaviour;

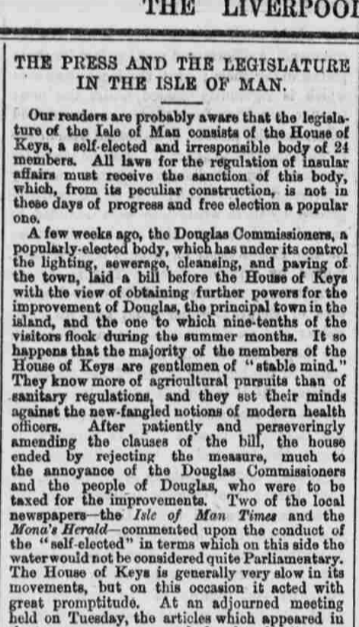

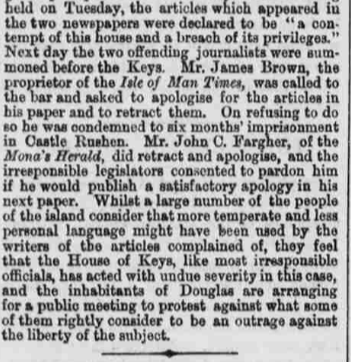

- The Isle of Man celebrates the Liverpool born journalist and Isle of Man Times founding editor James Brown (1815-81) who challenged the unrepresentative nature of the House of Keys and improved the democratic accountability of the island’s constitution. James was the mixed race grandson of an African-American slave. His name is on the ‘Manx Patriots’ Roll of Honour’ which can be seen in the foyer of Legislative Buildings and in the Royal Chapel at St John’s. He was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment in 1864 over articles which accused the Isle of Man’s House of Keys unelected legislators of being donkeys. He refused to apologise when summoned to the House of Keys and was accused of contempt and abuse of privileges. The decision to convict him was done in secret session. The editor of the Mona’s Herald, John C. Fargher, also summoned to appear, did apologise and was pardoned when he agreed to publish a retraction. Brown’s jailing started a freedom of the press campaign throughout Great Britain and Ireland. He continued to publish defiant articles, calling for freedom of the press and democracy while in prison. (See: https://www.iomtoday.co.im/news/james-brown-a-pioneer-for-many-reasons-236282)

Articles published in March 1864 in the Liverpool Mercury providing a report of James Brown’s imprisonment, and a statement of support from The Manchester Guardian circulated and published in other regional daily and weekly papers throughout Great Britain and Ireland.

- He was released after six weeks by the Court of Queen’s bench in London which had, and still has, jurisdiction over habeas corpus in the Crown Dependencies. The court ruled his detention was unlawful. This remains the only recourse to the English High Court (now King’s Bench division) in Crown Dependencies, including the Channel Islands, for arbitrary and irrational arrest and detention without due process. He successfully sued the House of Keys for depriving him of his liberty and was awarded £519 in damages. In 1866, the House of Keys became an elected body and in 1881 extended the franchise to unmarried women and widows over the age of 21 who own property, thus making the Isle of Man the first place to give some women the vote in a national election.

- The newspaper media and journalism on the Isle of Man during these years can be regarded as key contributing factors to achieving more representative government there. This progressive tradition continued in 2006 when the voting age was lowered to 16, though the minimum age for candidates remains 18. The Manx Patriots’ Roll of Honour also commemorates two more campaigning journalists who furthered the cause of democray on the island- Robert Fargher (1803-1863) and Samuel Norris (1875-1948). Both had also been jailed (Norris at the height of the Great War in 1916) as a result of publications and political clashes with the Isle of Man’s government and legislature.

- The first edition of McNae’s Essential Law for Journalists published in 1954 reported in the chapter on ‘Contempt of Court’ how the case of the ‘Isle of Man Times in 1938 described a police raid as “very amusing” and proceeded: “Liverpool constables, staying as guests in boarding houses, ordered drinks in unlicensed premises; and then, in true American fashion, with hooting of horns, and screeching of brakes, motor-cars drew up. Policemen jumped out and the show was complete.’ The paper was ordered to pay the costs of the High Court action which held this was a technical contempt.’

Tradition and legacy of freedom of the press in the Channel Islands

- There has been a tradition of a free press in the Channel Islands since the age of the Enlightenment towards the end of the 18th century and the time of the Napoleonic Wars. The Guernsey Star was founded in 1813. The island is at present served by one daily newspaper, The Guernsey Press, published six days a week with an online news site (https://guernseypress.com/news/). The Guernsey Evening Press was first published in 1897. In 1951 it merged with the morning Guernsey Star, and has become known as The Guernsey Press.

- The first newspaper published in Jersey was the French speaking Le Magasin de Jersey in 1784 and the first English language papers in Jersey were The British Press in 1822 followed by the Jersey Times in 1823 when they amalgamated. Jersey is currently served by one daily newspaper, the Jersey Evening Post, printed six days a week, and has been in circulation since 1890. It has an online news site. (See: https://jerseyeveningpost.com/). The printed newspaper media in the Channel Islands are IPSO regulated. Television news services are provided by the BBC (https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00cpbsj) and ITV (https://www.itv.com/news/channel) with newsrooms and programmes produced in the Islands. The BBC operates local radio stations in Jersey and Guernsey (https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/live:bbc_radio_jersey & https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/live:bbc_radio_guernsey) and there are also commercial radio stations. All of the broadcasting is subject to Ofcom regulation. Media conduct and content has to comply with Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code. There is a standalone Bailiwick Express online news service which describes itself as ‘a new virtual newspaper for Jersey [and Guernsey] combining the opportunities in website presentation and interactivity with e-mail reach to its readers.’ This is regulated by the Royal Charter approved IMPRESS and adheres to the Standards Code adopted by IMPRESS: http://www.impress.press/standards/. (See: https://www.bailiwickexpress.com/jsy/group/making-complaint) The Bailiwick Express operates an online news service with Jersey (https://www.bailiwickexpress.com/jsy/news/) and Guernsey editions (https://gsy.bailiwickexpress.com/) Bailiwick publishing broadcasts an online radio service which follows Ofcom regulation and also publishes the magazine Connect also regulated by IMPRESS.

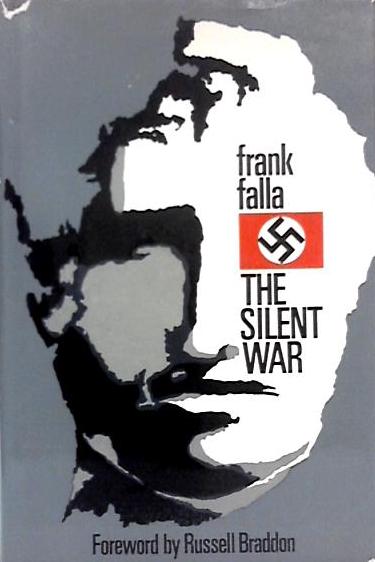

- The Channel Islands were the only part of the British Isles occupied by Nazi Germany during the Second World War and journalists died in their courageous efforts to bring BBC and Allied news to their fellow islanders through underground news sheet and other forms of clandestine communications. Great tribute and respect is owed to the editor of the daily Guernsey Star, Frank Falla, who during the occupation was part of a resistance group which published an underground paper titled the Guernsey Underground News Sheet, known as GUNS. (See: ‘Guernsey Underground News Service blue plaque unveiled’ at: https://guernseypress.com/news/2017/04/24/guernsey-underground-news-service-blue-plaque-unveiled/) He was betrayed and deported to Germany and was fortunate to survive the ordeal.

- While editing the Star he devised a method of strategic placement of stories in the newspaper’s lay-out so that islanders would be able to recognise those directed by the Germans for publication as propaganda and those actually written by Guernsey journalists.

The Guernsey Star edition for January 28th 1943 after the German defeat at the Battle of Stalingrad. Editor Frank Falla had a covert layout and design code so islanders would know which articles were free of their German occupiers’ interference and direction.

- I believe his memoir The Silent War should be on the reading list/syllabus of any journalism history and training course. Extensive research by Cambridge University academic Dr Gilly Carr and colleagues resulted in the location, donation and curating of Frank Falla’s personal papers which are now online at https://www.frankfallaarchive.org/ and https://www.frankfallaarchive.org/people/frank-falla/ The research has widened to cover all forms of resistance and defiance against Nazi occupation of the Channel Islands;

Media on Isle of Man and Secondary Media Law regulation

- Isle of Man media law is a combination of statute passed by its own leglislature/parliament, the Tynwald, and Manx customary law, an equivalent of common law developed by case law set in the island’s courts. The island has its own Human Rights Act, Strasbourg jurisprudence can be taken into account, UK precedents are not binding, but influential, and the final appeal from the Isle of Man’s legal system is to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London siting in the UK’s Supreme Court building in London’s Parliament Square, constituted by UK Supreme Court Justices (See https://www.jcpc.uk/);

- The island’s three printed weekly newspapers, Isle of Man Courier, Isle of Man Examiner and Manx Independent are in the Isle of Man Newspapers group owned by Tindle newspapers along with online news site Isle of Man Today (see: https://www.iomtoday.co.im/). These are all contracted to regulation by the Independent Press Standards Organisation, IPSO, and follow the Editors’ Code. Broadcast regulation of the island’s one public broadcasting service (Manx Radio at https://www.manxradio.com/) and two commercial radio stations is by the island’s own Broadcasting Act (see http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/1993/1993-0012/BroadcastingAct1993_2.pdf) and subsequent Communications Act 2021 (See: https://legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2021/2021-0003/CommunicationsAct2021_1.pdf) The Communications and Utilities Regulatory Authority CURA (See: https://www.gov.im/about-the-government/statutory-boards/communications-and-utilities-regulatory-authority/) is responsible for implementing the legislation including under section 46, the observance of a Standards Code set out under Schedule 3. This also ensures that licensed broadcasters establish and maintain procedures for the handling and resolution of complaints about the observance of those standards;

- Television news coverage is provided by UK or ‘across’ BBC and ITV services. People in the Isle of Man do not use the term ‘mainland’ as they regard themselves as the mainland. The UK television coverage is subject to Ofcom UK Broadcasting Code content and conduct regulation. Neither provide a specific news programme for the Isle of Man. No Isle of Man local television service has yet been licensed though should the economies of scale make it viable and achieve licensing approval by CURA, independent television broadcasting indigenous to the island remains a possibility;

- Consequently secondary media law is determined in print and associated online journalism under voluntary IPSO regulation by the Editors’ Code of Practice at https://www.ipso.co.uk/editors-code-of-practice/ guided by latest edition of Editors’ Codebook (144 pages) at: https://www.editorscode.org.uk/downloads/codebook/codebook-2022.pdf One page Code of Practice pdf file is available at: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2032/ecop-2021-ipso-version-pdf.pdf

- Schedule 3 of the Isle of Man Communications Act 2021 sets out broadcasting standards and objectives to be observed on pages 127 to 131 of the legislation. (See: https://legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2021/2021-0003/CommunicationsAct2021_1.pdf)

- These standards cover the protection of under 18s, preventing content which encourages or incites the commissioning of crime, ensuring the reporting of news with due accuracy, showing a proper degree of responsibility with respect to religious programmes, providing adequate protection from harmful or offensive material in programming, preventing unjust or unfair treatment in any programmes included in a broadcasting service, ensuring there is no unwarranted infringement of privacy in, or in connection with the obtaining of material included in any programme, and other rules on political advertising, sponsorship, and the prevention of subliminal communications. Schedule 3 also sets out ‘special requirements on impartiality’ which includes the preservation of due impartiality and the prevention of undue prominence of views and opinions in programming. Schedule 3 is very much a mirroring of the UK Ofcom Broadcsting Code;

- It seems The Isle of Man’s CURA and its predecessor body has been rarely asked to adjudicate and rule on complaints. The last case to generate significant coverage and attention was the suspension of Manx Radio presenter Stu Peters in 2020 over a phone-in exchange during which he challenged the concept of “white privilege.” (See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-isle-of-man-52936980) The matter was referred to the then Isle of Man’s Communications Commission. Peters was supported by The Free Speech Union which intervened on his behalf. (See: https://freespeechunion.org/letter-to-the-isle-of-man-communications-commission-about-stuart-peters/) The Commission decided the broadcast did not breach the standards code, and the presenter was cleared of any wrongdoing and reinstated. (See: https://www.manxradio.com/news/isle-of-man-news/stu-peters-did-not-breach-programme-code-says-broadcasting-watchdog/ and https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-isle-of-man-53171352) In 2021 Stu Peters left Manx Radio to become a candidate in the General Eelection (See: https://twitter.com/StuManx/status/1408782858030825477) was elected to the House of Keys, and appointed Chairman of the Board of the Isle of Man’s Post Office (See: https://www.iompost.com/media-centre/isle-of-man-post-office/Stu-Peters-Chairman/);

Libel/defamation law on the Isle of Man

- Libel in the Isle of Man has been determined by the Libel and Slander Act 1892, Defamation Act 1954, and the most recent legislative provisions of the Law Reform Act 1997, and case law- some of which goes as far back as the celebrated case in 1872 of Laughton v the Bishop of Sodor and Man at the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council which determined issues over absolute privilege and the construction of malice in political communications. (See: http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/1892/1892-0007/LibelandSlanderAct1892_1.pdf and http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/1954/1954-0005/DefamationAct1954_1.pdf and http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/1997/1997-0001/LawReformAct1997_2.pdf and https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/uk/cases/UKPC/1872/1872_88.html)

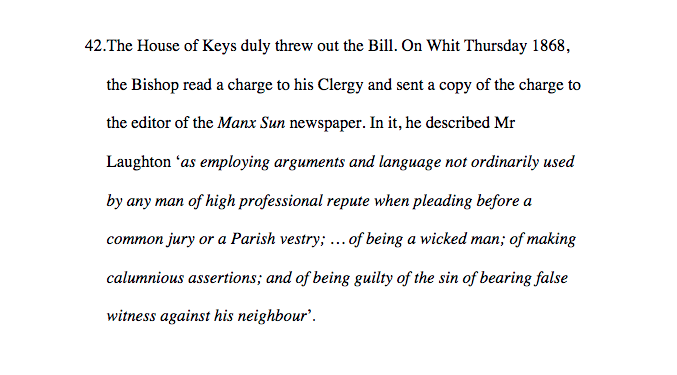

- In 2013 Lord Neuberger summarised the Laughton v Bishop of Sodor and Man libel case over three succinct paragraphs 41 to 43 in his delivery of ‘The Annual Caroline Weatherill Memorial Lecture’ on the subject of The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the 21st Century Isle of Man:-

- Isle of Man defamation law does not have the clarity of the recent reforming and largely consolidating Defamation Act 2013 of England and Wales and navigating and understanding it in the context of any potential litigation should certainly require specialist legal advice from a lawyer qualified and practising in the Manx jurisdiction. The criminal libel processes still applying from the 1892 Libel and Slander Act require the approval of a High Court of Justice under section 10, which in the Isle of Man would be a judicial office-holder called a Deemster. Section 12 sets out defences of the publication being for the public benefit, being true (justification), being fair and accurate, and published without malice.

- Libel/defamation is also a civil wrong/tort in the Isle of Man legal jurisdiction and it would seem that the defences cited in the 1892 legislation should be available in civil litigation. The 1997 Law Reform Act legislates in detail for the absolute privilege defence when reporting court proceedings, and the Isle of Man’s Tynwald, the Council or the Keys, and qualied privilege when reporting other government bodies and public meetings. The enactment of the Isle of Man’s own 2001 Human Rights Act in 2006 means that under Section 2 Strasbourg jurisprudence on freedom of expression law must be taken into account and the island’s courts need to have particular regard for freedom of expression under Section 11 when prior restraint orders are sought. (See: http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2001/2001-0001/HumanRightsAct2001_1.pdf)

- There are few public domain reports of Isle of Man libel cases. One such by the Guardian in 2002 ‘Poet faces jail in libel battle with millionaire’ at https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/nov/12/davidleigh contained unflattering descriptions of the Island’s legal system as ‘neanderthal’, ‘idiosyncractic’ and ‘Kafkae-esque,’ with no protection of journalists’ sources law and a Human Rights Act which at that time was not in force. The case of Albert Gubay v the late Roly Drower resulted in Mr Drower being fined for contempt of court when he refused to disclose the identity for the source of allegations he had posted online. (See: ‘Chasing a Manx tale. The Isle of Man is proud of its consensus form of government, but it can be a costly place to express dissent, writes Carol Coulter’ at: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/chasing-a-manx-tale-1.1170605);

Need to legislate for protection of journalist sources law revealed in notorious libel case

- A proposed 2018 Isle of Man Contempt of Court Bill under clause 14 ‘provides that it is neither an offence nor a contempt of court to refuse to disclose a source of information contained in a publication unless the disclosure is required in the interests of justice, or in the interests of the national security of the Island or the United Kingdom, or to prevent crime or disorder.’ This reflects the provision in Section 10 of the UK 1981 Contempt of Court Act. The bill is to be considered for legislation in the next few years and following the commencement in 2006 of the island’s Human Rights Act 2001, it is certainly possible for journalists and their lawyers to draw upon Strasbourg protection of sources jurisprudence in the interim and additionally if and when the Contempt Bill is enacted. (See Contempt of Court Bill 2018 at https://consult.gov.im/attorney-generals-chambers/contempt-of-court-bill-2018/supporting_documents/ContemptofCourtBill2018_V01.pdf and explanatory notes at: https://consult.gov.im/attorney-generals-chambers/contempt-of-court-bill-2018/supporting_documents/Explanatory%20notes.pdf);

- Isle of Man libel law reached the consideration of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the case of Nugent & Anor v Willers (Isle of Man) [2019] UKPC 1 (16 January 2019) at https://www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKPC/2019/1.html on the matter of interpreting the primary limitation period for bringing defamation actions which usually runs from one year after the date of publication as imposed by section 4A of the Isle of Man Limitation Act 1984 and the discretion to exclude that time limit which is conferred on the court by section 30A of the Act. This was not a journalism publication case and turned on whether the claimant acted promptly and reasonably after discovering the cause of action in a letter. The letter originated in 2009 and its existence was discovered by the claimant in 2013;

- Isle of Man defamation law is therefore a matrix of Manx Acts of Parliament and case law. It is missing the serious harm rule, one publication rule, statutory defences for truth, public interest, honest opinion, academic journal/conference qualified privilege, and innocent dissemination/web operator’s defence present in the 2013 Defamation Act of England and Wales. However, libel cases and other secondary media law infractions are rare. In 2021 and 2020 there were no complaints made or upheld against Tindle’s Isle of Man newspaper series: Isle of Man Examiner, Isle of Man Courier, and Manx Independent and its associated news website. (See: https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2270/tindle-annual-statement-2021_compressed.pdf & https://www.ipso.co.uk/media/2040/tindle-newspapers-annual-statement-2020.pdf) The only IPSO complaint recorded against a Isle of Man newspaper was in 2020 Dobson v Isle of Man Examiner with a resolved decision through IPSO mediation. See: https://www.ipso.co.uk/rulings-and-resolution-statements/ruling/?id=00397-20 This was reported by Hold The Front Page 15th April 2020 ‘Magistrate’s delivery blamed for weekly’s inaccurate court story’ at: https://www.holdthefrontpage.co.uk/2020/news/magistrates-delivery-blamed-for-weeklys-inaccurate-court-story/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=facebook;

- Section 8 of the Isle of Man Law Reform Act 1997 provides a defence on responsibility for defamation if a person can show: (a) he was not the author, editor or publisher of the statement complained of, (b) he took reasonable care in relation to its publication, and (c) he did not know, and had no reason to believe, that what he did caused or contributed to the publication of a defamatory statement. Under 8(3) ‘A person shall not be considered the author, editor or publisher of a statement if he is only involved’ under (d) ‘as the broadcaster of a live programme containing the statement in circumstances in which he has no effective control over the maker of the statement’ and (e) ‘as the operator of or provider of access to a communications system by means of which the statement is transmitted, or made available, by a person over whom he has no effective control.’ In theory this should provide a defence for broadcasters faced with a live guest who without any warning or reasonable expectation makes defamatory allegations and for journalism website publishers or social media platforms with comment streams which are not pre-moderated. Where potential libel is brought to the attention of a news website/social media publisher, it could be argued they should be able to avail themselves of the defence by removing the material within a reasonable amount of time. Under 8(5) the legislation provides ‘a reasonable care’ evaluation and ‘regard shall be had to — (a) the extent of his responsibility for the content of the statement or the decision to publish it, (b) the nature or circumstances of the publication, and (c) the previous conduct or character of the author, editor or publisher.’ See: http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/1997/1997-0001/LawReformAct1997_2.pdf ;

- Under Section 9 of the Law Reform Act 1997, the Isle of Man has an offer of amends provision in libel law which is a means of settling early and limiting damages and costs. Under section 14 there is a provision for summary disposal where ‘The court may dismiss the plaintiff’s claim if it appears to the court that it has no realistic prospect of success and there is no reason why it should be tried.’ Summary relief is defined as: (a) a declaration that the statement was false and defamatory of the plaintiff; (b) an order that the defendant publish or cause to be published a suitable correction and apology; (c) damages not exceeding £10,000 or such other amount as may be prescribed by order of the Council of Ministers; (d) an order restraining the defendant from publishing or further publishing the matter complained of.’ Under section 13, the legislation states ‘In defamation proceedings the court shall not be asked to rule whether a statement is arguably capable, as opposed to capable, of bearing a particular meaning or meanings attributed to it.’

- Section 19 of the Law Reform Act enacts an absolute privilege defence in libel for ‘A fair and accurate report of proceedings in public before a court to which this section applies, if published contemporaneously with proceedings.’ In 19(3) the absolute privilege applies to any court in the British Islands, EU Court of Justice, ECtHR in Strasbourg and any international criminal tribunal established by the Security Council of the United Nations. It also applies to fair and accurate reports of proceedings where reporting had been postponed by court order. Section 20 states that the qualified privilege defence can be defeated by malice and where the defendant ‘(a) was requested by [the Plaintiff] to publish in a suitable manner a reasonable letter or statement by way of explanation or contradiction, and (b) refused or neglected to do so’;

- The 1954 Defamation Act made defamatory statements in broadcasting a permanent form of libel. Under Section 2 in slander (the spoken form of defamation) ‘it shall not be necessary to allege or prove special damage’ when defaming somebody in the plantiff’s ‘office, profession, calling, trade or business.’ Under Section 5 in respect of ‘words containing two or more distinct charges against the plaintiff, a defence of justification shall not fail by reason only that the truth of every charge is not proved if the words not proved to be true do not materially injure the plaintiff’s reputation having regard to the truth of the remaining charges.’ Under Section 6 in respect of words consisting partly of allegations of fact and partly of expression of opinion, a defence of fair comment shall not fail by reason only that the truth of every allegation of fact is not proved if the expression of opinion is fair comment having regard to such of the facts alleged or referred to in the words complained of as are proved’;

Open justice and legal system on Isle of Man

- Court proceedings in the Isle of Man follow the Open Justice convention and principle. Manx law has a distinct system of binding precedent based on cases brought before the Island’s courts. Precedents in the English legal system, when relevant and applicable, are persuasive. The supreme court for the Isle of Man is the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. The Isle Man’s highest appellate court is the Staff of Government Division. The lowest courts in the Isle of Man are the summary courts, Coroner of Inquests, Licensing Court, Land Court, etc. These courts are presided over by magistrates. There are two stipendiary magistrates, the High Bailiff and the Deputy High Bailiff, along with lay justices of the peace.

- The superior court of the Isle of Man is the High Court of Justice of the Isle of Man, consisting of a Civil Division and an appeal division, called the Staff of Government Division.The judges of the High Court are the deemsters, appointed by the King (acting on the advice of the Secretary of State for Justice in the United Kingdom), and the judicial officers, appointed by the Lieutenant Governor. The High Bailiff and the Deputy High Bailiff are ex officio judicial officers, and additional judicial officers (full-time or part-time) may be appointed. Civil matters are usually heard at first instance by a single deemster sitting in the High Court. Criminal proceedings are heard at first instance before either the High Bailiff or the Deputy High Bailiff or a bench of lay magistrates, in less serious cases. More serious criminal cases are heard before a deemster sitting in the Court of General Gaol Delivery. In a defended case the Deemster sits with a jury of seven (twelve in cases of treason or murder). Civil and criminal appeals are dealt with by the Staff of Government Division. Appeals are usually heard by a deemster (the one not involved with the case previously in the High Court or Court of General Gaol Delivery) and the Judge of Appeal. An explanation of the Isle of Man Courts of Justice is set out at https://www.courts.im/ and this includes listings of forthcoming cases and hearings. A database of Isle of Man judgements online is maintained at https://www.judgments.im/content/home.mth

- The Isle of Man’s criminal justice system is explained in a detailed report published in 2018. (See: https://www.gov.im/media/1364203/iom-code-of-practice-for-victims-and-witnesses-2312019.pdf with ‘a service which focuses on the needs of victims’ https://www.gov.im/news/2021/may/23/service-focuses-on-needs-of-victims/). Page 49 of the criminal justice system guide explains ‘Journalists are able to attend hearings at the Courts however, reporting restrictions may apply. The media does not report the names of offenders, victims or witnesses if they are under the age of 18 years. Only in very exceptional circumstances, after an application has been made by the media to the presiding Deemster, may permission be given to publish names.’ The guide also explains the identity of adult witnesses are protected ‘Only in very limited circumstances. Generally, if you are giving evidence you will be required to give your name to the court. There are very few restrictions placed upon the media in terms of what can and what cannot be reported. Information that might lead to the identification of a child witness or a defendant aged less than 18 years is prohibited.’

Isle of Man Sexual Offences legislation enhrines anonymity for defendants unless and until found guilty as well as complainants

- The Sexual Offences and Obscene Publication Act Isle of Man 2021 makes it a criminal offence to publish anything which could lead to the identification of a sexual offence defendant until convicted. (See: https://legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2021/2021-0010/SexualOffencesandObscenePublicationsAct2021_1.pdf) This makes the Isle of Man legal jurisdictional approach to sex offence defendants unique in the British Islands. The relevant part of the act is set out out in Sections 139 to 146. The legislation includes a ’backstop’ provision that allows a judge to lift the naming ban in the public interest if it is judged to be a ’substantial and unreasonable’ restriction on the reporting of the court proceedings. The anonymity clause only applies to the Manx media, and the same case could be covered without restriction in the UK press. However, the risk of ’jigsaw identification’, where readers can piece together the information of a case from two different media sources, means Isle of Man media may decide to avoid covering a case because the missing details reported elsewhere makes them liable.

- Section 140 of this act ‘Anonymity of suspects and defendants alleged to have committed certain offences. Non-statutory guidance explaining the changes brought by Part 8 regarding Anonymity and the effect these changes have in connection with reporting of sexual offences proceedings’ is now due for implementation during the first quarter of 2024. The Isle of Man Tynwald was due to discuss the regulations in March 2024 and if approved, the law will come into force from March 25th. It should go without saying that this legislation provides lifelong anonymity for anyone who complains of being the victim of a sexual offence from the time they make the accusation.

- The legislation mirrors UK law at Section 139(1) ‘no matter relating to that person shall during that person’s lifetime be included in any publication if it is likely to lead members of the public to identify that person as the person against whom the offence is alleged to have been committed.’ Under 139(4) the matters ‘include in particular — (a) the person’s name; (b) the person’s address; (c) the identity of any school or other educational establishment attended by the person; (d) the identity of any place of work; and (e) any still or moving picture of the person.’ This provision could make it a potential offence to include a pixelated still or film purportedly concealing identity because there may be remaining features which are identiable to somebody who may know the victim/complainant. Section 146 defines ‘picture’ as to include ‘a likeness however produced.’ The Act also provides the power to additionally grant anonymity to witnesses in sexual offence trials. Section 142 sets out offences to which the anonymity restrictions can be applied and states the reasons and circumstances under Section 143 and 144 where they could be varied and lifted by order of the court.

- The legislation was considered controversial and the debate generated is covered in the articles ‘Anonymity law will lead to cases going unreported’ 12th November 2020 at https://www.iomtoday.co.im/news/courts/anonymity-law-will-lead-to-cases-going-unreported-238097 and ‘Defendants accused of rape to have identity protected’ 11th December 2019 at https://www.iomtoday.co.im/news/politics/defendants-accused-of-rape-to-have-identity-protected-231894 UK British media need to be conscious of the potential legal position of a news website which part covered Isle of Man news. When the legislation was scrutinised by the Tynwald a spokesman for the Department of Home Affairs said: ’If the website had an Isle of Man presence and an article naming a defendant on it was published, the bill talks about the editor having committed an offence, and the penalties are specified’;

Protection of children in Isle of Man legal system

- The Isle of Man’s Children and Young Persons’ Act 2001 at Section 8 sets out the protections for children involved in legal proceedings. At Section 69 the statutory principle is established that ‘Every court in dealing with a child or young person who is brought before it, either as an offender or otherwise, shall have regard to the welfare of the child or young person.’ Section 75 provides for clearing court while child or young person is giving evidence though ‘bona fide representatives of a newspaper or news agency’ are not excluded and can remain to carry on their reporting duties. Section 80 makes it a criminal offence to publish a photograph or any information leading to the identification of children involved in legal proceedings: ‘no written report of any proceedings in any court shall be published in the Island, and no report of any such proceedings shall be included in a relevant programme for reception in the Island, which —(a) reveals the name, address or school, or (b) includes any particulars calculated to lead to the identification, of any child or young person concerned in those proceedings, either as being the person against or in respect of whom the proceedings are taken or as being a witness therein.’ (See: http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2001/2001-0020/ChildrenandYoungPersonsAct2001_1.pdf ) The age of criminal responsibility on the Isle of Man is 10. The legislation also says ‘the words “conviction” and “sentence” shall not be used in relation to children and young persons dealt with summarily.’ Children are aged 17 and under and Isle of Man law recognises them as adults when they reach the age of 18.

Plan to legislate for media contempt law in Isle of Man

- In the next few years it is expected that the Isle of Man Parliament will be evaluating, updating and passing its Contempt of Court Bill into legislation. It seeks to synchronise media contempt law with the provisions of the UK’s 1981 Contempt of Court Act with formal powers to issue court orders to postpone the reporting of proceedings to avoid prejudice to future court cases, prohibit publications of the identity of witnesses withheld from the hearing, a strict liability rule of substantial risk of serious prejudice applying to the media after arrests have been made in criminal enquiries, and the prohibition of filming, sound recording and photography in court. There are no problematic case histories in media conduct on the Isle of Man to make this legislation urgent. In 2018 somebody who was not a journalist and attending a criminal trial on the island took photographs in court and there was confusion about the legal powers available to deal with the disruption. It was reported that the case had to be abandoned because the photographs during the closing stages of the trial included the jurors and the prosecuting advocate. The jury had to be discharged. See ‘Fair trials: A loophole is found in Manx court laws’, 23rd August 2018 at: https://www.iomtoday.co.im/news/courts/fair-trials-a-loophole-is-found-in-manx-court-laws-223181 The proposed legislation provides for an appeal process to challenge the imposition of reporting restrictions, a defence for discussion of public interest matters that are merely incidental to court proceedings taking place, the protection of jury deliberations, and as previously mentioned a statutory protection of journalists’ sources. See: https://consult.gov.im/attorney-generals-chambers/contempt-of-court-bill-2018/supporting_documents/ContemptofCourtBill2018_V01.pdf & https://consult.gov.im/attorney-generals-chambers/contempt-of-court-bill-2018/

GDPR, Freedom of Information and Copyright law in Isle of Man

- The Isle of Man also has GDPR and Data Protection legislation which is similar to the UK position though different in taking a direct approach. Key parts of the GDPR include a widened definition of personal data, new obligations for processors as well as boosted rights for individuals. The Isle of Man implemented the GDPR into its law so that it can continue to do business with EU countries via an Order made under a new Data Protection Act 2018 (See https://legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2018/2018-0010/DataProtectionAct2018_1.pdf ) This enables the Isle of Man to bring in EU laws relating to data protection. (See https://www.gov.im/about-the-government/data-protection-gdpr-on-the-isle-of-man/ and https://www.gov.im/media/1361222/gdpr_weboutlinedblue.pdf The laws contained in this framework will substantially influence the concept of privacy law in the Isle of Man’s jurisdiction combined with case law vectoring Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights- respect for private and family life, home and correspondence and enshrined in the Manx Human Rights Act;

- The Isle of Man has its own Freedom of Information Act and regime of request to public bodies and appeal against refusal. (See http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2015/2015-0008/FreedomofInformationAct2015_1.pdf and https://www.gov.im/about-the-government/freedom-of-information/make-a-freedom-of-information-request/ ) The system and approach is very similar to that in England and Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland and the Channel Islands. And Isle of Man journalists have encountered similar frustrations about the effectiveness of FOI to serve public interest imperatives. See ‘There’s a public interest in releasing ‘bullying’ report but we’re not going to do it’ 7th December 2019 at: https://www.iomtoday.co.im/news/education/theres-a-public-interest-in-releasing-bullying-report-but-were-not-going-to-do-it-231796 ;

- Copyright and intellectual property law on the Isle of Man is determined by the primary legislation statute law the Copyright Act of 1991, followed by the Copyright Amendment Act of 1999, establishing database rights and remedies and another Copyright Amendment Act of 2014, which largely amended penalties and remedies for infringement. (See: http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/1991/1991-0008/CopyrightAct1991_5.pdf, and http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/1999/1999-0012/CopyrightAmendmentAct1999_1.pdf and http://www.legislation.gov.im/cms/images/LEGISLATION/PRINCIPAL/2014/2014-0007/CopyrightetcAmendmentAct2014_1.pdf) The Isle of Man legal jurisdiction hears copyright claims, disputes and litigation in its own Copyright Tribunal (See: https://www.courts.im/court-procedures/tribunals-service/tribunals/). There are other Tynwald Acts covering IP such as the Design Right Act 1991, Performers’ Protection Act 1996, Patents Act 1977, Registered Designs Act 1949, Trade Marks Act 1994, Community Trade Mark Order 1998 (SD 671/98) and Community Trade Mark Regulations 1998 (SD 672/98).

- The duration of copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work lasts from 70 years after the death of the author, and the copyright residing in sound recordings and films covers the communication of a work to the public by electronic transmission. Isle of Man copyright law is substantially synchronised with that of the UK and European Union. The island’s Department of Economic Development seeks to modernise IP as explained at https://www.gov.im/categories/business-and-industries/intellectual-property/modernisation/ though it does not propose to seek the adoption of legislation for an artist’s resale right (droit de suite) or public lending right.

Channel Islands legal systems

- The main systems cover the Bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey and they are both very similar, with a final route of appeal on matters of law to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. Channel Islands’ law has a considerable amount of French influence. For example, the first tier criminal Magistrates Court can resemble in process the inquisitorial function of the French examining magistrate who will investigate a criminal allegation, make a finding of guilty or not guilty and then decide the sentence alone. The French trditions determine some of the unique terminology describing the court roles. In Jersey the Centenier is an honorary police officer who presents the case. The equivalent of the Magistrates Clerk is called the Greffier, or Deputy Greffier.

- The more serious criminal cases in Jersey are heard in Royal Court trials where the professional judge determining matters of law is called the Bailiff or Deputy Bailiff and usually two Jurats who decide the facts in criminal cases and also rule on the sentence. Where the prison sentence for the crime being tried is more than 4 years, the Royal Court will be constituted by the Bailiff and five jurats. In the Jersey system occasionally a jury of 12 members of the public might be summoned in cases heard before the Assizes Court and they will determine the issue of guilt in respect of the accused.

- Jurats are not professional judges but do become specialists in their field of judicial participation which also includes the civil system where they can assess damages as well. In the Bailwicks of Jersey and Guernsey Jurats also preside over land conveyances and liquor licensing.

- Jurats are not randomly selected members of the public from the electoral role. At any one time the Jersey and Guernsey legal systems are served by twelve Jurats who are indirectly elected in Jersey by an electoral college constituted of States Members and members of the legal profession. They serve until retirement at the age of 72, or earlier once they have served in the role for six years. They have two further important constitutional roles: as presiding officers in public elections, known in the Islands as autorisés to oversee polling and declare the results and constituting the Bailiwick’s Prison Board of Visitors where they are responsible for the proper care and treatment of prisoners and hear their complaints and representations.

- In Guernsey jurats are elected by a process known as the States of Election comprising of the Island’s judiciary, law officers and Anglican clergy. In the more serious criminal cases the Bailiff (professional judge) sits with seven jurats known as the Full Court, with cases heard by Bailiff and two jurats known as the Ordinary Court. When robed in court, jurats in Jersey will be in red and in Guernsey they will be in purple. The separate legal jurisdiction of Alderney is run by six jurats (appointed by the Crown) and the senior judge known as the Judge of Alderney. Alderney jurats operate as judges of both fact and law assisted by a learned clerk in civil and criminal cases. BBC report ‘How to become a Jurat in Jersey’ See http://news.bbc.co.uk/local/jersey/hi/people_and_places/the_states/newsid_8399000/8399699.stm Bailiwick Express podcast ‘The Interview: Diversity on the Royal Court bench with Jurat Collette Crill.’ See: https://bailiwickexpress.transistor.fm/episodes/the-interview-diversity-on-the-royal-court-bench-with-jurat-collette-crill

- Some useful online guides to the legal system in the Bailiwick of Jersey: Jersey Legal Information Board See: https://www.jerseylaw.je/ Pages/default.aspx; Online resource provided by the government of Jersey on crime and justice. See: https://www.gov.je/CrimeJustice/Pages/default.aspx and Jersey court structure http://www.justcite.com/kb/editorial-policies/terms/jersey-court-structure/ Some useful online guides to the legal system in the Bailiwick of Guernsey. Guernsey Legal System Resources. See: https://www.guernseylegalresources.gg. The Royal Court of Guernsey. See: https://guernseyroyalcourt.gg/ Law Officers of the Crown in the Bailiwick of Guernsey. See https://guernseyroyalcourt.gg/

Media Law in the Channel Islands’ legal jurisdictions

- Broadly speaking the media law applying in these jurisdictions is similar to that of the UK and as has already been stated journalists working press, online, radio and television services are subject to the same professional standards and values regulated by Ofcom (broadcasting services) IPSO (Jersey Evening Post and Guernsey Press) and IMPRESS (online Bailiwick Press and printed magazine). However, specific nuances and differences as well as local customs and practices could require the expertise of specialist lawyers qualified in these legal jurisdictions and I would recommend external news organisations to commission the expertise, services, and advice of professional journalists working in the Channel Islands when this is felt necessary.

- Media law litigation and/or prosecution is very rare in the Islands’ jurisdictions. Reporting restictions protecting the publication of anything which could identify youths aged 17 and under and sexual offence complainants apply. Youth Courts sit without the public, but accredited reporters can be present. Jersey Youth Court procedure determined by Criminal Justice (Young Offenders) (Jersey) Law 1994 states: ‘Journalists may attend provided that nothing reported shall enable a Defendant directly or indirectly to be identified.’ See: https://www.gov.je/SiteCollectionDocuments/Government%20and%20administration/ID%20YouthCourtBooklet%202007-11-10%20BJL.pdf;

- Defamation issues are pursued through civil legal action and a full Jersey libel trial determined by jurats was described and reported on by Informm in 2012 ‘Case Law, Jersey: Pitman v Jersey Evening Post, cartoon not defamatory’ See: https://inforrm.org/2012/05/23/case-law-jersey-pitman-v-jersey-evening-post-cartoon-not-defamatory/ In 2013 the Guardian reported on a case leading to criminal consequences for a libel defendant refusing to comply with the outcome of defamatory legal action. “Former Channel Islands politician sentenced to three months in prison for refusing to take down ‘highly defamatory’ articles” See: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/nov/04/jersey-stuart-syvret-jailed-blog-allegations;

- The courts in Jersey and Guernsey have inherent powers to control their proceedings and protect what they regard as the administration of justice and this does on occasion lead to tension and disagreement with Open Justice considerations argued by journalists and their publications. In 2002 the Jersey Evening Post contested a reporting ban which the Guardian reported was ‘the culmination of a year-long battle to report a civil case surrounding millions of pounds deposited in three Jersey registered trust funds.’ See: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2002/oct/14/pressandpublishing.law

- There is evidence in recent years that the frequency of Open Justice derogations is increasing. On 10th January 2023, Magistrate Bridget Shaw imposed restrictions (at a hearing that the media was barred from attending) preventing details of the case from being reported, under an Article 89 Order of the Criminal Procedure (Jersey) Law 2018 to “protect the administration of justice.”‘ See: https://www.bailiwickexpress.com/jsy/news/flame-thrower-threat-students-was-cry-help-court-hears/#.ZF_I3XbMIkh The Jersey Evening Post published an essay criticising a lack of transparency and open justice in the island on 21st January 2023, highlighting that journalists were increasingly finding restrictions placed on what they can report.

- On 22nd Nov 2019 Bailiwick Express applied for the removal of reporting restrictions https://www.bailiwickexpress.com/jsy/news/express-applies-removal-reporting-restrictions/?t=i#.ZB479xXP1ow and on 2nd December 2019 it reported that its restrictions application was rejected See: https://www.bailiwickexpress.com/jsy/news/express-reporting-restrictions-application-rejected/#.ZB48ixXP0kg The legal system in Jersey does publish court lists and court case outcomes (for only up to seven days after the event.) See: https://www.gov.je/Government/NonexecLegal/JudicialGreffe/Pages/CourtLists.aspx#anchor-2

- There is an argument for legislation in both Bailiwicks to underscore Open Justice values in the context of practice and law in the United Kingdom as well as reference to Strasbourg jurisprudence in respect of the European Convention on Human Rights and Article 10 Freedom of Expression. For example they could follow the Isle of Man in legislating for an equivalent Contempt of Court Act guaranteeing protection of journalists’ sources, the right to report court hearings and a system of appeal and challenge of reporting restrictions. Jersey’s Human Rights Law came into force on 10 December 2006 following the passage of Human Rights Jersey law in 2000. See: https://www.jerseylaw.je/laws/current/Pages/15.350.aspx and section 12 Freedom of Expression:

(1) This Article applies if a court is considering whether to grant any relief which, if granted, might affect the exercise of the Convention right to freedom of expression.

(2) If the person against whom the application for relief is made (the “respondent”) is neither present nor represented, no such relief is to be granted unless the court is satisfied –

(a) that the applicant has taken all practicable steps to notify the respondent; or

(b) that there are compelling reasons why the respondent should not be notified.

(3) No such relief is to be granted so as to restrain publication before trial unless the court is satisfied that the applicant is likely to establish that publication should not be allowed.

(4) The court shall have particular regard to the importance of the Convention right to freedom of expression and, where the proceedings relate to material which the respondent claims, or which appears to the court, to be journalistic, literary or artistic material (or to conduct connected with such material), to –

(a) the extent to which –

(i) the material has, or is about to, become available to the public; or

(ii) it is, or would be, in the public interest for the material to be published; and

(b) any relevant privacy code.

(5) In this Article –

“court” includes a tribunal; and

“relief” includes any remedy or order (other than in criminal proceedings).

- See also Jersey Human Rights Working Group Main provisions of Human Rights Jersey Law A brief explanatory document at: https://www.gov.je/SiteCollectionDocuments/Government%20and%20administration/ID%20Human%20rights%20guidance%20note%20091217%20ME.pdf The Bailiwick of Guernsey also passed Human Rights Law in 2000 which has now been put into force. See: https://www.guernseylegalresources.gg/CHttpHandler.ashx?documentid=80709 Freedom of Expression in the consolidated text is covered by Section 11:

11. (1) This section applies if a court is considering whether to grant

any relief which, if granted, might affect the exercise of the Convention right to

freedom of expression.

(2) If the person against whom the application for relief is made

(“the respondent”) is neither present nor represented, no such relief is to be granted

unless the court is satisfied –

(a) that the applicant has taken all practicable steps to

notify the respondent, or

(b) that there are compelling reasons why the respondent

should not be notified.

(3) No such relief is to be granted so as to restrain publication

before trial unless the court is satisfied that the applicant is likely to establish that

publication should not be allowed.

(4) The court must have particular regard to the importance of the

Convention right to freedom of expression and, where the proceedings relate to

material which the respondent claims, or which appears to the court, to be

journalistic, literary or artistic material (or to conduct connected with such material),

to –

(a) the extent to which –

(i) the material has, or is about to, become

available to the public, or

(ii) it is, or would be, in the public interest for the

material to be published,(b) any relevant privacy code.

(5) In this section –

“court” includes a tribunal, and

“relief” includes any remedy or order (other than in criminal

proceedings).

- The legal profession and judiciary in these small Islands’ legal jurisdictions have been discussing the setting of legal boundaries in media communications about the process of law particularly in the new age of online social media. Robin Gist, an Advocate with the Law Officers of the Crown, Guernsey, in an article in 2016 analysed ‘the effect of social media on confidence in the judiciary of a small jurisdiction, where the limited number of judges means their judgments are subject to the most public of scrutiny. The article considers whether more can, or should, be done to ensure that confidence in the judiciary is retained at its very highest.’ See: ‘Protecting the administration of justice in a small jurisdiction’ in the Jersey and Guernsey Law Review at: https://www.jerseylaw.je/publications/jglr/PDF%20Documents/JLR1602_Gist.pdf

- The article sets out useful factual information about the laws protecting the disruption of legal proceedings by contempt of court and references the Children (Guernsey and Alderney) Law 2008 (as amended), s 115(5) which determines that any person who publishes any matter in contravention of that section (which effectively prohibits the publishing of any report which might identify a child concerned in proceedings, be that child the subject of proceedings or a witness), is guilty of an offence and liable to imprisonment and a fine. Media Contempt under the customary law is referenced to the case of BBC v Law Officers, a judgment handed down by the Guernsey Court of Appeal on 18 November 1988. Mr Gist effectively analyses this precedent in his article:

The Court of Appeal set out (at 6) that—

“Although Contempt of Court has long been a part of the law of the Island of Guernsey, there has been no authoritative definition . . . of the constituent parts of the offence.”

The Court of Appeal endorsed the Deputy Bailiff’s decision to—

“look for guidance primarily to the Law of England . . . [having] regard not so much to the common law . . . as to the provisions of section 2 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981”,

apparently implying that it was appropriate to use the 1981 Act for guidance, notwithstanding that it had (at 9) “effected substantial changes in the [previously common] Law of Contempt in the United Kingdom”. The reasons cited for this were that—

(a) the Contempt of Court Act 1981 had ensured the UK’s compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights (specifically art 10);

(b) that Convention extends to Guernsey; and (at 8)—

“there would be less room for differences between one jurisdiction and another in the case of interference with the authority of the judiciary than in the case for example of the ‘protection of morals’ which may vary with differences in time and place.”

The Court of Appeal held (at 11) that—

“the test to be applied . . . can properly be derived by way of analogy from the terms of section 2 [of the Contempt of Court Act 1981] . . . the section, in its application applies a double test . . . First there has to be some risk that the proceedings will be affected at all. Second there has to be a prospect that, if affected the effect will be serious.”

- Mr Gist recognised that there is still an option for customary law in Guernsey to recognise contempt of court in publications which can be proved to be deliberate and intended to interfere with the administration of justice: ‘Thus, publications which are intended to impede or prejudice the administration of justice remain punishable as contempt of court at common law in England & Wales, and, one might argue, pursuant to the customary law in Guernsey. It is clear that a publication which is not punishable as a contempt under the strict liability rule may nevertheless be punishable as a contempt at common (and so arguably customary) law.’

- Mr Gist also observed ‘It is interesting to note that there seems to be no statutory basis for any contempt of court in Jersey. Certainly, as in Guernsey, there is no equivalent to the Contempt of Court Act 1981. Moreover, it would appear that the courts in Jersey have not applied, by analogy or otherwise, the provisions of the 1981 Act. On the other hand, the Jersey courts have been far more ready to find that a contempt of court exists.’ He referenced the 2013 Syvret case where refusal to comply with an order of the court after defamatory proceedings led to a jail sentence of three months for contempt of court.

Freedom of Information, privacy law and Data Protection GDPR in Channel Islands jurisdictions

- Privacy law operates through the development of customary case law and like with other jurisdictions in the UK and British Isles is underpinned by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Privacy protection is also statutorily framed by the Islands’ GDPR. The Data Protection (Jersey) Law 2018 sets out the rights of individuals in respect of their personal data as well as the obligations and conditions organisations must follow to process it. GDPR reshapes the way in which sectors manage data, as well as redefines the roles for key leaders in businesses. The Freedom of Information (Jersey) Law 2011 was legislated for in order to meet the aim of making the Government of Jersey accountable and transparent in the way they operate and make decisions. These spheres of legal duties, rights, and obligations are regulated by the Jersey Office of the Information Commissioner. See: ‘Jersey’s Data Protection, GDPR and Freedom of Information Laws’ at https://jerseyoic.org/dp-foi-laws/ and Jersey Office of the Information Commissioner at: https://jerseyoic.org/ In Guernsey The Office of the Data Protection Authority is the independent regulatory authority for the purposes of The Data Protection (Bailiwick of Guernsey) Law, 2017 and associated legislation. See: https://www.odpa.gg/

- There is a debate that Freedom of Information law in the Bailiwick of Guernsey is weaker than in the island jurisdictions of Jersey and Isle of Man because it is determined by the operation of only a Freedom of Information Code. See: https://www.gov.gg/CHttpHandler.ashx?id=149645&p=0 You can assess the operation of the code with case histories at: https://www.gov.gg/information See ITV News 2021 ‘Guernsey politicians vote against introducing Freedom of Information law’ at: https://www.itv.com/news/channel/2021-06-17/guernsey-politicians-vote-against-introducing-freedom-of-information-law See also Guernsey Press ‘Time not right for freedom of information law – Scrutiny’ at: https://guernseypress.com/news/2021/05/14/time-not-right-for-freedom-of-information-law—scrutiny/

Copyright Law Channel Islands’ jurisdictions

- Copyright law in Jersey is similar to that of the UK and protection engages as soon as a work is created and is recorded in some way, for example, on paper or as a digital file. It is not possible to make a formal registration for creative work in Jersey that is not patents, trademarks and designs and there is no register to lodge with. (or the UK). Citizens Advice provides an excellent summary of IP law in the Bailiwick of Jersey at https://www.citizensadvice.je/copyright-patents-in-jersey/ The main legislative reference point is Intellectual Property (Unregistered Rights) (Jersey) Law 2011 with an official version of consolidated legislation compiled and issued under the authority of the Legislation (Jersey) Law 2021 and is set out at: https://www.jerseylaw.je/laws/current/Pages/05.350.aspx There is also an excellent summary of ‘Intellectual Property (Unregistered Rights) (Jersey) Law 2011’ by the legal firm of Bedell and Christin at: https://www.bedellcristin.com/knowledge/briefings/intellectual-property-unregistered-rights-jersey-law-2011/ ;

- Copyright law in the States of Guernsey, again, is similar to that of the UK. For example, Under the Copyright (Bailiwick of Guernsey) Ordinance, 2005, Copyright in literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works expires at the end of the period of 70 years from the end of the calendar year in which the author dies. Copyright (Bailiwick of Guernsey) Ordinance, 2005 is set out at https://www.guernseylegalresources.gg/ordinances/guernsey-bailiwick/i/intellectual-property/copyright-bailiwick-of-guernsey-ordinance-2005/ with a printable version at https://www.guernseylegalresources.gg/CHttpHandler.ashx?documentid=52628 The States of Guernsey has an Intellectual Property Office which advises on the jurisdiction’s IP law. See: https://ipo.guernseyregistry.com/article/3865/Intellectual-Property-Office-Home-Page Guernsey does have a distinctive IP facility under The Image Rights (Bailiwick of Guernsey) Ordinance 2012, which enables the registration of a personality and “images” associated with the personality. The Guernsey Image Rights Legislation has been explained by the legal firm Ogier at: https://www.ogier.com/news-and-insights/insights/guernsey-image-rights-legislation/ and discussed in a 2012 Guardian article ‘Image rights register for celebrities proposed in Guernsey’ at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2012/jun/26/image-rights-register-celebrities-guernsey. This innovative reform in IP law was also discussed in an article by David Evans, Director of Collas Crill IP, Guernsey ‘Can You Protect Your image Like Your Brand?’ published in the World Intellectual Property Organisation’s magazine in May 2015 at: https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2015/02/article_0008.html