UK Media Law Pocketbook Second Edition published 30th November 2022

By Tim Crook

Media Law is one of the most dynamic areas of the UK’s legal systems. There are continual changes in case and statutory law. This chapter tries to keep you up-to-date so far as possible. Each addition to the foregoing online chapters will be copied here chronologically.

If you have decided to enter the profession of journalism and do your very best to report accurately and fairly without fear or favour and to navigate the increasingly treacherous waters of UK media law, you have the author’s admiration and thanks.

You are a true agency of democracy, open justice and holding power to account. You work in the spirit of the proverb carved into the granite of the Central Criminal Court- ‘Defend the children of the poor and punish the wrongdoer’- Line 4 of Psalm 72 Deus, judicium of the Old Testament.

Other lines 5-7 from Psalm 72 are compliments and tributes to the good people of journalism through the ages:

‘They shall fear thee, as long as the sun and moon endureth, from one generation to another.

He shall come down like the rain upon the mown grass, even as the drops that water the earth.

In his time shall the righteous flourish; yea, and abundance of peace, so long as the moon endureth.’

-o-

If you are reading and accessing this publication as an e-book such as on the VitalSource platform, please be advised that it is Routledge policy for clickthrough to reach the home page only. However, copying and pasting the url into the address bar of a separate page on your browser usually reaches the full YouTube, Soundcloud and online links.

The companion website pages will contain all of the printed and e-book’s links with accurate click-through and copy and paste properties. Best endeavours will be made to audit, correct and update the links every six months.

United Kingdom gains three places in 2024 world press freedom index.

There has been some moderately good news in the United Kingdom’s evaluation for press and media freedom by Reporters Without Borders in their 2024 global press freedom index.

See detailed briefing at: https://kulturapress.com/2024/05/07/united-kingdom-gains-three-places-in-2024-world-press-freedom-index/

And pdf file version below.

Update for Chapters 1 and 3- UK Supreme Court confirms case law precedent that all crime suspects are entitled to reasonable expectation of privacy anonymity 16th February 2022

It is a highly significant ruling by UK Supreme Court Justices in Bloomberg LP (Appellant) v ZXC (Respondent)

Lord Reed, Lord Lloyd-Jones, Lord Sales, Lord Hamblen, Lord Stephens presiding.

From the court’s press summary:-

The Respondent (“ZXC”) is a US citizen who worked for a company which operated overseas. He and his employer were the subject of a criminal investigation by a UK Legal Enforcement Body (the “UKLEB”). During that investigation, the UKLEB sent a confidential Letter of Request (the “Letter”) to the authorities of a foreign state seeking, among other things, information and documents relating to ZXC. The Letter expressly requested that its existence and contents remain confidential.

The Appellant (“Bloomberg”), a well-known media company, obtained a copy of the Letter, on the basis of which it published an article reporting that information had been requested in respect of ZXC and detailing the matters in respect of which he was being investigated. After Bloomberg refused to remove the article from its website, and following an unsuccessful application for an interim injunction, ZXC brought a successful claim against Bloomberg for misuse of private information.

ZXC claimed that he had a reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to: (1) the fact that the UKLEB had requested information relating to him in the context of its investigations, and (2) the details of the matters that the UKLEB was investigating in relation to him. The first instance judge held that Bloomberg had published private information that was in principle protected by article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the “ECHR”); and that in balancing ZXC’s rights against those of Bloomberg under article 10 ECHR, the balance favoured ZXC. Bloomberg’s appeal against that judgment was dismissed by the Court of Appeal. Bloomberg now appeals to the Supreme Court.

Judgment

The Supreme Court unanimously dismisses the appeal. It holds that, in general, a person under criminal investigation has, prior to being charged, a reasonable expectation of privacy in respect of information relating to that investigation. Lord Hamblen and Lord Stephens give the sole joint judgment, with which the other Justices agree.

Full bailii.og ruling on this link: United Kingdom Supreme Court >> Bloomberg LP v ZXC [2022] UKSC 5 (16 February 2022 )

The full UK Supreme Court case resources page for Bloomberg LP (Appellant) v ZXC (Respondent)

The full ruling in Bloomberg v ZXC as downloadable pdf file

bloombergvzxcuksc-2020-0122-judgment

Reaction and analysis:-

Press Gazette reports: ‘Bloomberg Supreme Court defeat means criminal suspects have media anonymity before charge.‘

Hold The Front Page report: ‘The Society of Editors has hit out after the UK Supreme Court ruled that a person under criminal investigation has a reasonable expectation of privacy prior to charge.’

Guardian reports: ‘Bloomberg loses landmark UK supreme court case on privacy. Media will find it harder to publish information about people in criminal investigations.’

5RB report and analysis of ‘Supreme Court judgment on criminal suspects’ privacy rights: ZXC v Bloomberg.’

Sun newspaper Editorial: ‘Decision to protect the privacy of ALL suspects puts public in far greater danger.’

Update for Chapter 4 The legal jeopardy for journalists when arrested while covering news events in the UK.

The widespread criticism of arrests by Hertfordshire police of journalists and photographers covering Just Stop Oil protests, including an LBC/Global reporter is an opportunity to explore the law and ethics over reporters’ rights when covering stories of this kind.

What are the rights of journalists if wrongfully stopped from doing their job by the police, and even worse arrested for doing so?

This does not constitute qualified legal advice, but journalists should always have direct contact with their employer’s lawyers or professional legal advice in the event of arrest while carrying out their work.

It is also recommended that professional journalists covering public news events are members of professional journalist organisations such as the National Union of Journalists (NUJ), Chartered Institute of Journalists (CIoJ) or British Association of Journalists (BAJ).

The UK National Police Chiefs’ Council accredited Press Card states categorically ‘The National Police Chiefs’ Council recognise the holder of this card as a bona fide newsgatherer.’

Furthermore the College of Policing guidance on media relations (updated for 2022) states under the heading ‘Reporting from a scene’:-

‘Reporting or filming from the scene of an incident is part of the media’s role and they should not be prevented from doing so from a public place. Police have no power or moral responsibility to stop the filming or photographing of incidents or police personnel. It is for the media to determine what is published or broadcast, not the police. Once an image has been recorded, the police have no power to seize equipment, or delete or confiscate images or footage, without a court order.’

College of Policing guidance is available online at: https://www.college.police.uk/app/engagement-and-communication/media-relations

The largest police force in the UK is the Metropolitan Police in London who have an online public declaration of media rights for journalists and members of the public and what they expect their officers to understand and comply with at: https://www.met.police.uk/advice/advice-and-information/ph/photography-advice/

‘Freedom to photograph and film

Members of the public and the media do not need a permit to film or photograph in public places and police have no power to stop them filming or photographing incidents or police personnel.

Creating vantage points

When areas are cordoned off following an incident, creating a vantage point, if possible, where members of the media at the scene can see police activity, can help them do their job without interfering with a police operation. However, media may still report from areas accessible to the general public.

Identifying the media

Genuine members of the media carry identification, for instance the UK Press Card, which they will present on request.

The press and the public

If someone distressed or bereaved asks the police to stop the media recording them, the request can be passed on to the media, but not enforced.

Access to incident scenes

The Senior Investigating Officer is in charge of granting members of the media access to incident scenes. In the early stages of investigation, evidence gathering and forensic retrieval take priority over media access, but, where appropriate, access should be allowed as soon as is practicable.’

Apologies to journalists by Hertfordshire Police and independent review of what happened

Hertfordshire Police instituted an independent review of the arrests of journalists covering the Just Stop Oil protests which was carried out by the Cambridgeshire Constabulary. It concluded that the journalists should not have been arrested. The Chief Constable of Hertfordshire Police directly apologised to the arrested journalists.

M25 arrests review See: https://www.herts.police.uk/news/hertfordshire/news/2022/november/m25-arrests-review/

Chief Constable Charlie Hall said: ‘“Whilst the review has correctly concluded that the arrests of the journalists were not justified, and that changes in training and command need to be made, it found no evidence to indicate that officers acted maliciously or were deliberately disproportionate. They made mistakes and I now reiterate my apologies.’

As a result of the review Hertfordshire Police accepted five recommendations:

1.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider selecting commanders with commensurate skills and experience when balanced against the nature of the operation.

2.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider ensuring that mentors collate with commanders for the duration of the operation.

3.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider ensuring that all commanders have access to Public Order Safety (POPS) advisors.

4.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider affording commanders with the ability and capacity to maintain accurate decision logs.

5.Hertfordshire Constabulary should consider ensuring that all officers engaged with public order activity complete the NUJ package and identified learning is shared.

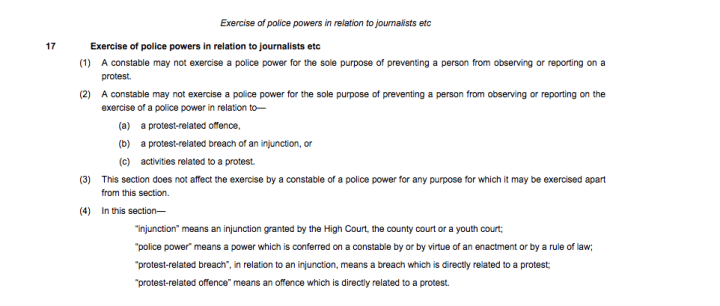

Legislative change to the new Public Order Act in 2023 to protect journalists from arrest when covering public protests

An amendment in the House of Lords to the Public Order Act 2023 passed on 7th February 2023 introduced statutory safeguards protecting journalists from arrest when observing or reporting on the type of protests carried out by climate change activists.

The aim has been to separate in law the professional work of journalists of merely being there to report from any suspicion or belief on the part of the police that by doing so they are conspiring or participating in ‘direct political action’ that is so disruptive as to amount to actual public order offences.

Section 17 under subsection (1) states the police may not use their powers ‘for the sole purpose of preventing a person from observing or reporting on a protest.’

Subsection (2) prevents the police from using their powers for the sole purpose of preventing a person from observing or reporting on the exercise of a police power in relation to:

(a) a protest-related offence,

(b) a protest-related breach of an injunction, or

(c) activities related to a protest.

These safeguards were proposed by the former director of Liberty and Labour peer Baroness Chakrabarti who explained that the amendment was designed to protect journalists, legal observers, academics and bystanders who might observe or report on protests or the police’s use of powers related to protests.

The amendment was approved by a majority of 283 to 192 and is expected to be brought into effect on 2nd July 2023.

Section 17 of the Public Order Act 2023

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/15/section/17

Press Gazette: ‘Protection for journalists added into anti-protest Public Order Bill. Campaigners had warned the Public Order Bill could make arrests of journalists “commonplace.”‘

See: https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/protection-for-journalists-added-into-public-order-bill/https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/protection-for-journalists-added-into-public-order-bill/

Some key journalists’ rights criteria when covering public news events.

1.Journalists have Article 10 freedom of expression and media rights under the European Convention of Human Rights and UK Human Rights Act (HRA) 1998 combined with English common law freedom of expression rights to cover news events without hindrance or interference from government authorities.

2.The National Press Card recognised by the National Police Chiefs’ Council should be a guarantee to any UK police officer that the holder is a legitimate professional journalist.

3.In the absence of this kind of card, any other identifying document or card from an employing organisation or association, even a commissioning letter/email from an editor, should be sufficient evidence of professional bone fide status.

4. Professional journalists never participate in protests and demonstrations and properly distinguish themselves from those people they are reporting on. This should be obvious to police officers. Everything should be done to avoid any ambiguity on this point. This is why the value of professional impartiality extends to a journalists’ personal social media and online presence.

5.Professional journalists have a right to cover news events using multimedia technology from public places and this is lawful behaviour. Privacy law issues should be a matter for the civil courts and not criminal police investigation.

6.Police officers should not ask journalists how and why they know protests or demonstrations are taking place. This is a prima facie interference with the Article 10 right to the protection of journalists’ sources.

7. Police officers need to have reasonable cause to suspect any journalist has committed an offence before proceeding to arrest, detention, and other processes such as taking DNA and photographs. If they do not, they face potential action for false arrest and unlawful imprisonment.

8. Police officers are obliged under the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act to perform reasonable steps when making any request of an individual in respect of an arrest or interruption of a working journalist. It is always useful for journalists or their colleagues to make notes, record/film the conduct and behaviour of the officer(s) though it is understandable why this might be difficult in some circumstances.

9. What should be done if police officers mistakenly arrest a journalist while lawfully covering a news event? It is advisable to politely ask the officers what their ‘reasonable suspicion’ amounts to. It is not advisable for journalists to resist the police officers physically in any situation. It might help to always make it clear that there is no intention to obstruct, or give actual interference with the police officers carrying out their duties. It might also help to try and stress the advantage of clarifying any misunderstanding; avoiding the waste, expense, cost, and paperwork of complaints and future litigation.

10.There is no harm in professional journalists reminding the police that they have been lawfully covering a public interest news event, they have properly identified themselves as such and the arrest is not reasonable or necessary in law. The circumstances and personalities of the arresting officers might be such that silence and not over-stating the issue could be the best strategy. There may be an advantage in suggesting that arresting police officers sought the advice of their senior officers and commanders in respect of their actions.

11. The police may have a power under the Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 (Section 19) to seize under lawful search digital reporting equipment with photographs, video and sound, but journalists are entitled to the protection under 1984 PACE that this material is protected as ‘special procedure material.’ The police must get a court order to search this material and only a Crown Court judge can issue a warrant. The police can seize equipment in order to ascertain whether or not the content is ‘special procedure material,’ but if the journalism equipment, smart phone, digital recording devices and SD cards, are labelled “Special Procedure Material collected for the purposes of journalism under PACE 1984” then the police can be in no doubt about their legal obligations.

12.There is further protection for ‘confidential journalistic’ material under the 1984 PACE legislation that effectively blocks police access, even with application for court orders, unless there is an investigation for a very serious indictable offence. When journalists collect information and media material subject to a journalistic confidentiality agreement it is advisable to label this as ‘Confidential Journalistic Records under 1984 PACE.’ However, journalists might have difficulty getting the courts to recognise the ‘confidential’ designation if they have been recording a public event because actions in public can be hardly evaluated as ‘confidential’- only the special procedure material protection applies. It can certainly be argued that a smartphone is likely to include confidential journalistic records and journalists would have a right to withhold the password accessing the device.

13. It would seem journalists and photographers had been arrested by Hertfordshire Police for alleged ‘conspiracy to commit a public nuisance.’ The professional journalistic coverage of a public interest news event is not a criminal nuisance. This includes photographing, digitally videoing and sound recording such an event. It can be argued that for such an arrest to be ‘reasonable’, the police would need to have evidence that journalists agreed to protest and disrupt with the activists. No professional journalists carrying out their impartial reporting duties would ever agree to such a course of action. It can be strongly argued that journalists receiving information from protest groups that ‘something is going to happen at such a time and in such a place’ does not amount to ‘conspiracy to commit a public nuisance.’ Such communications should have the shield of journalist source protection law under Article 10 Human Rights Law. Journalists have the right not to disclose anything about such communications.

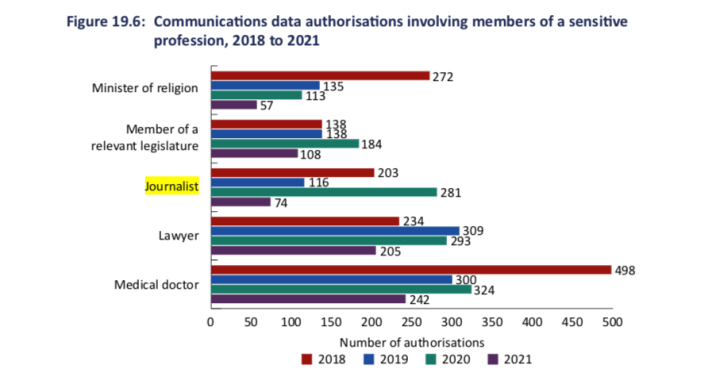

14.Unfortunately the Investigatory Powers Act 2016 does give the police (and other state bodies) powers to access mobile, computer and digital communications information between journalist sources and journalists if they are investigating serious crime which is defined as any criminal offence with a minimum jail sentence of one year’s imprisonment. The oversight by the Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office (IPCO) and The Office for Communications Data Authorisations (OCDA) is done in secret by judicial commissioners and civil service with very limited accountability. If journalist communications have been intercepted and the connections made by the police, journalists have no right to know about this or even represent their position in any review by a judicial commissioner. Consequently, journalists should think carefully about the digital trails of their communications with sources.

15. Do journalists have any positive legal obligation to report prior knowledge of potential criminal behaviour to the police? At the moment there is only a positive duty under

Section 38B(1) and (2) of the Terrorism Act 2000 which makes it an offence if someone does not inform the police if he/she believes that someone they know is in preparation of acts of terrorism. The maximum sentence in respect of Section 38B is for a term not exceeding five years’ imprisonment, although it is a defence to prove that he/she had reasonable excuse for not making the disclosure. Obviously the disruptive actions of Just Stop Oil protesters and environmental activists are not acts of terrorism. In any communications between journalists and their sources in protest groups, it is advisable to avoid receiving any information about the detail and nature of protests and events being planned. It is enough to receive information about time and place in order to avoid any potential ethical dilemmas generated by the nature of the full detail of prior knowledge offered.

16. Some self-evident observations:- professional journalists covering Just Stop Oil disruption can obviously do so in a lawful way from public places. It would not be lawful for them to join the activists on an M25 gantry. Similarly if a criminal fugitive who has escaped custody contacts a journalist and wants to provide an interview, this should only be done remotely. The journalist should not agree to meet the fugitive for an interview unless the fugitive agrees to surrender back into custody at the same time. There are obviously risk assessment and personal safety issues for the employing organisation to resolve with their journalist(s) beforehand.

17. Journalists need to be provided with effective identifying documentation, media cards and lanyards to demonstrate their bona fide status as journalists when covering public interest news events. If they have not been issued with a UK Press Card Authority card, they should be in possession of an accreditation letter from their editor and employing/commissioning news publisher with contact numbers and details for verification.

18. Some useful background case histories-

-o-

The wrongful arrest of two investigative journalists and the search of their homes by the police in Northern Ireland on behalf of the Durham Constabulary led to legal condemnation by the Northern Ireland High Court and the award of hundreds of thousands of pounds in damages. See Belfast Telegraph story in 2020: ‘Police to pay out millions after settling case over journalist arrests’ at: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/police-to-pay-out-millions-after-settling-case-over-journalist-arrests-39799447.html

And ‘Journalist gets police apology for arrest over Kent barracks photos. Force admits detention of Andy Aitchison after he covered protest at Napier barracks was unlawful.’ See Guardian story in October 2021: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2021/oct/22/journalist-gets-police-apology-for-arrest-over-kent-barracks-photos

Updates for Chapter 9- Northern Ireland libel reform enacted 2022

While the book was in production, the Northern Ireland Assembly passed the Defamation Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 which substantially reforms the law of libel in this legal jurisdiction, though does not fully mirror the reforms in the England and Wales 2013 Defamation Act.

Very briefly the act mirrors the 2013 Defamation Act applying to the England and Wales jurisdiction providing statutory defences for truth, honest opinion, public interest, and peer reviewed statement in an academic or scientific journal, but does not offer the serious harm threshold for libel and single publication rule.

Here is the structure of the legislation with its sixteen sections.

1.Truth

2.Honest opinion

3.Publication on matter of public interest

4.Peer-reviewed statement in scientific or academic journal etc

5.Reports etc protected by privilege

6.Action against a person not domiciled in the UK

7.Trial to be without a jury unless the court orders otherwise

8.Power of court to order a summary of its judgment to be published

9.Powers of the court

10.Special damage

11.Review of defamation law

12.Interpretation

13.Consequential amendments and savings etc

14.Commencement

15.Short title

The new legislation has been impressively analysed and discussed by Tony Jaffa for Hold The Front Page with the column titled ‘Are libel law reforms enough?’

And also by Ciaran O’Shiel and Holly Johnston for the Informm website with the headline ‘The Defamation Act (NI) 2022, A Swing and a Miss.’

Challenging anonymity orders applied for by defendants on the grounds publicity increased the risk of their self-harming

Northern Ireland court reporter and Local Democracy journalist Tanya Fowles has been seeking to halt a developing trend for courts issuing anonymity orders for trial defendants who say that publicity may cause them to self-harm.

She has been challenging and campaigning against the practice for many years. In November 2021, she succeeded in resisting an application by lawyers representing a woman seeking a life-long anonymity order following convictions for fraud and money-laundering offences.

In addition, District Judge Bernie Kelly at Armagh Magistrates Court rejected an application for anonymity due to the risk of self-harm in respect of a man accused of attempted sexual communication with a child.

The Judge was reported saying: ‘I appreciate this is a balancing critique of rights but I always quote the tagline of the Washington Post – Democracy Dies in Darkness. Never truer words were spoken. Light must be shone into the dark recesses, to ensure the public can have confidence and all of us are answerable. As far as I’m concerned the press is the Fourth Estate and are essential to ensuring the other three branches of our constitution do so in a fit and proper way.’

However, there have been other cases where lifelong anonymity in Northern Ireland courts have been sustained for convicted sex offenders on the basis of publicity being accepted as a threat to their mental health.

In June 2023 Tanya unsuccessfully sought the support of Northern Ireland’s most senior judge to reverse the legal jurisdiction’s unique position of providing this protection to paedophiles beyond the practice of giving lifelong anonymity to exeptional convicted prisoners in notorious murder cases.

She argues that prisoners making such threats in their mitigation would be eligible for immediate placement on the Supporting Prisoners At Risk scheme to prevent self-harm and such orders are disproportionate and contrary to what lifetime anonymity is usually reserved for.

Tanya Fowles, who works for the Enniskillen-based weekly the Impartial Reporter, received the BBC’s Local Democracy Reporter of the Year award in 2022 in recognition of her challenging bids by court defendants, including convicted paedophiles, to have reporting restrictions imposed on their cases.

See the following Hold The Front Page reports:

Judge refuses to back reporter’s fight against paedophile’s lifelong anonymity (22 June 2023)

Reporter thwarts murder case secrecy bids after double court fight (2 June 2023)

Second paedophile wins lifelong anonymity after suicide threat (23 April 2023)

Judge slams colleague after journalists barred from naming alleged fraudster (27 Feb 2023)

Press barred from naming alleged abuser over ‘paedophile hunters’ threat risk

Reporter to fight alleged paedophile name ban after probing police evidence

Judge sides with journalist over bid to keep alleged sex offender’s address secret

Alleged sex abuser fails in secrecy bid after judge’s error

Reporter hits out after judge withdraws right to name paedophile

Reporter demands top judge acts on defendants’ ‘self-harm’ secrecy bids

Court reporter wins six-year fight as judge slams self-harm anonymity bids

Court reporters warned to expect ‘deluge’ of paedophile anonymity bids

Journalist who battled spurious criminal secrecy bids named top LDR

New legislation in Northern Ireland passed which makes it a criminal offence to report anything leading to the identification of persons suspected of sexual offences prior to charge. These laws were commenced and came into effect 28th September 2023.

The Justice (Sexual Offences and Trafficking Victims) Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 has provisions across Sections 12 to 18 which criminalise any publication leading to the identification of people accused of sexual offences unless they are charged by investigating police. This mirrors the UK legislation anonymising teachers prior to charge.

However, it is unique in extending the anonymity for people accused of sexual offences for 25 years after their deaths.

The legislation is also different from the rest of the UK in extending anonymity for 25 years after the deaths of sexual offence complainants.

Anyone wishing to discharge these restrictions has to make an application to a Magistrates Court and this includes living sexual offence complainants and anyone accused of such crimes who has not been charged.

The legislation was given Royal Assent 27th April 2022 and Sections 1 to 11, 12 to 18, and 19 commenced 28 September 2023.

The online public record of the legislation states ‘The other provisions of this Act come into operation on such day or days as the Department of Justice may by order appoint.’

These unusual statutory provisions are the result of the Northern Ireland Assembly taking into account the recommendations of Sir John Gillen’s report in 2019 who investigated the law and serious sexual offences in Northern Ireland.

The report itself is 714 pages and takes many original and internationally law comparative approaches to the issues investigated.

At this stage it is useful to mark the following proposed changes that are particularly relevant to journalists and publishers:

Section 8. Sexual offence complainants in Northern Ireland will have additional anonymity beyond their lifetime- ‘during the period of 25 years beginning with the date of the complainant’s death…’

Section 9. During the 25 years following the sexual complainant’s death, interested parties may apply to a magistrates court to disapply or vary the anonymity. These would include ‘persons interested in publishing matters’, the late complainant’s representative, or a family member. The court would have the power to revoke and vary the anonymity:

(a)in the interests of justice, or

(b)otherwise in the public interest

Section 10. Penalties for breaching the anonymity are a maximum of 6 months imprisonment and/or a Level 5 fine which used to be capped at £5,000, but after legislative change in 2015 became unlimited.

Section 12. Statutory anonymity for anyone suspected of having committed a sexual offence in Northern Ireland unless charged by the police. ‘No matter relating to the suspect is to be included in any publication if it is likely to lead members of the public to identify the suspect as a person who is alleged to have, or is suspected of having, committed the offence.’

The legislation when commenced will be retrospective. The anonymity will last ’25 years beginning with the date of the suspect’s death. Information protected includes:

a)the suspect’s name;

(b)the suspect’s address;

(c)the identity of any school or other educational establishment attended by the suspect;

(d)the identity of any place of work;

(e)any still or moving picture of the suspect.

Section 13. This section sets out the sexual offences that apply and includes abuse of position of trust, possession of extreme pornographic images, and possession of a paedophile manual.

Section 14. This section sets out how the restriction can be disapplied during the suspects’ lifetimes and 25 years after their deaths.

This legislation indicates that journalists and publishers cannot rely on the written consent of the suspect. Both suspect or the Chief Constable of Police Service Northern Ireland have the only locus standi to make the application while the suspect is alive. Following the suspect’s death ‘a person interested in publishing matters’, representative of the suspect or a member of the suspect’s family are able to apply to the Magistrates Court to disapply or vary the duration of the anonymity within the 25 year period.

Anonymity of suspects- Sections 11 to 18 inclusive

Section 19. This provides the courts in Northern Ireland trying sexual offences and any appeal arising to exclude the public from the proceedings. An exception to the exclusion includes ‘bona fide representatives of news gathering or reporting organisations.’

Northern Ireland’s Department of Justice provided the following ‘Media guidance for editors: Legislative changes for information’ on 28th September 2023.

(i) Extended Anonymity of Victim and Complainants – Sections 8 to 11 of the Justice (Sexual Offences and Trafficking Victims) Act (Northern Ireland) 2022(external link opens in a new window / tab) (‘the SOTV Act’). Currently, under the Sexual Offences (Amendment) Act 1992 publication of anything that would help identify the victim or complainant of a sexual offence is prohibited during their lifetime. The SOTV Act amends the 1992 Act to extend these reporting restrictions for 25 years after their death. From commencement on 28 September 2023, anonymity for 25 years after their death will apply to all living victims or complainants of sexual offences regardless of when the sexual offence took place. Where a victim or complainant has died 25 years or less before the commencement date, the extended anonymity will apply. The penalty for breach of anonymity has been increased to up to 6 months’ imprisonment and applies to both lifelong and extended anonymity after the death of the victim. Applications can be made to the magistrates’ court to dis-apply or modify the reporting restrictions after death.

(ii) Anonymity of the Suspect Sections 12 to 18 (external link opens in a new window / tab) of, and Schedule 3(external link opens in a new window / tab). These provisions allow for the anonymity of the suspect in a sexual offence case up to the point of their charge. Where a suspect is not subsequently charged, his or her anonymity will be protected during their lifetime and for 25 years after their death. Under the new law, it will be an offence to publish anything that would lead to the identification of the suspect, punishable with up to six months’ imprisonment. A suspect is defined as a person against whom an allegation of having committed a sexual offence has been made to the police or whom the police are investigating in connection with a sexual offence but where no allegation has been made. Once a suspect has been charged with a sexual offence the protection of anonymity ends. On commencement on 28 September 2023, the anonymity provisions will apply retrospectively. Applications to dis-apply or modify the reporting restrictions can be made to the magistrates’ court.

(iii) Exclusion of the public from Crown Court – Section 19 Justice (Sexual Offences and Trafficking Victims) Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 (external link opens in a new window / tab)Where a sexual offence case is tried on indictment in the Crown Court, only certain persons are allowed to remain in the court. Before the trial, the court must make an exclusion direction which will specify those who are allowed to remain in the court. Under an exclusion direction, all persons are excluded from the court with the exception of those as prescribed in the SOTV Act:

- Members and officers of the court;

- Persons directly involved in the proceedings. This includes: the complainant, the accused, legal representatives acting in the proceedings, any witness while giving evidence in the proceedings, any person acting in the capacity of an interpreter or other person appointed to assist a witness or an accused and members of the jury;

- A relative or friend of the complainant nominated by the complainant and specified in the direction. Only one person may be nominated. A relative or friend of the accused nominated by the accused and specified in the direction. Only one person may be nominated;

- Bona fide representatives of news gathering or reporting organisations;

- Any other person specified in the direction as a person excepted from the exclusion.

Where the complainant in the sexual offence case has died before the start of the trial an exclusion direction does not apply. An exclusion direction has effect from the beginning of the trial until the proceedings, in respect of each serious sexual offence to which the trial relates, have been determined (by acquittal, conviction or otherwise) or abandoned. If the trial continues in respect of other non-sexual offences, the exclusion direction no longer applies. The exclusion direction does not apply during any time when a verdict is being delivered in relation to the accused. The public are allowed to be in the court when a verdict is being delivered.

(iv) Exclusion of the public from appeal hearings – (external link opens in a new window / tab)Section 19 Justice (Sexual Offences and Trafficking Victims) Act (Northern Ireland) 2022(external link opens in a new window / tab). The provisions also place a duty on the Court of Appeal to make an exclusion direction before the start of an appeal hearing or a hearing on an application for leave to appeal against a conviction or sentence (or both) for a serious sexual offence. The exclusion provisions do not apply to proceedings on applications for leave to appeal which are considered by a single judge mechanism on papers submitted. With the exception of the following, the guidance above on exclusion of the public from the Crown Court also applies to the exclusion of the public from appeal hearings:

- Where the complainant has died before the start of the hearing, an exclusion direction does not apply. Where the complainant has died after the hearing has commenced, the exclusion direction continues to apply;

- The exclusion direction does not apply when the following decisions of the court are being pronounced: A decision to grant or refuse leave to appeal; a decision on an appeal; a decision to grant or refuse leave for the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) to make a reference on the grounds of undue leniency; a decision on a reference on the grounds of undue leniency by the DPP.’

The media lawyer Sam Brookman analysed the commencement of the Northern Ireland legislation for the regular Jaffa Law Column at Hold The Front Page 3rd October 2023 ‘NI takes lead on anonymity for sexual offence suspects.’

She made the point that statutory anonymity for sexual offence suspects does not substantially change the law because since the sequence of privacy cases such as Richard v BBC, Sicri v Associated Newspapers and ZXC v Bloomberg, the UK Supreme Court consolidated the precedent of the reasonable expectation of privacy for all crime suspects.

However, she points out ‘the main difference created by the statutory measures in Northern Ireland is that the potential penalty for publishers is far more severe – a criminal conviction and up to 6 months in prison’ and ‘The right to claim civil damages will not have been affected.’ That is not the case in the Scottish jurisdiction though.

While recognising a laudable aim in ‘victims to have greater confidence in the criminal justice system’ Sam Brookman raises the issue ‘what price open justice? Some might be asking whether the NI Assembly [has] gone too far and forgotten the importance of open justice. And is this just a start, with this Act being a precedent which the other home countries will follow?’

The commencement of these new and unique laws applying in Northern Ireland has attracted some critical coverage in other journalistic publications.

See Mail Online 29th September 2023 ‘New anonymity law for suspected sex offenders which would have made it illegal to call Jimmy Savile a paedophile comes into force in Northern Ireland.’ See: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12572853/New-anonymity-law-paedophiles-Northern-Ireland.html

Belfast Telegraph 28th September 2023 ‘New laws granting anonymity to suspects in sexual offence cases come into force in NI.’ See: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/new-laws-granting-anonymity-to-suspects-in-sexual-offence-cases-come-into-force-in-ni/a1224888762.html

Belfast Telegraph 29th September 2023 “New NI anonymity laws ‘would have prevented reporting of Savile allegations” See: https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/northern-ireland/new-ni-anonymity-laws-would-have-prevented-reporting-of-savile-allegations/a146787537.html

Pdf file Media Law Briefing on this subject

NorthernIrelandanonymityforpeopleaccusedofsexoffencesuntilchargedMediaLawBriefingDownload

Coroner in Northern Ireland given the power to order an academic researcher to reveal the names of potential witnesses interviewed for a PhD thesis.

The unnamed academic researcher ‘XX’ was issued an order by the Coroner conducting ongoing inquest proceedings in relation to the deaths of three individuals, Lawrence McNally, Tony Doris and Michael Ryan at Coagh on 3 June 1991.

‘XX researched a thesis between 2011 and 2016 which was awarded a PhD by St Andrews University in Scotland titled Tir Eoghain Rebellion, a local war: a study of insurgency and counter-insurgency in post-1969 County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.

But the thesis is embargoed from publication until 2066 and is held securely by the university and the author’s solicitors.

Three of the researcher’s confidential interviewees, T, F and L, referred to the events at Coagh, and their identities are subject of a notice served under section 17A of the 1959 Coroner’s Act Northern Ireland.

‘XX’ has resisted the order on the basis the information itself is of little or no relevance to the questions which the inquest is obliged to answer, and there is a weighty public interest in academic historical research and in the preservation of confidentiality agreements.

The researcher draws an analogy with the protection afforded to journalists and their sources, and relies upon section 10 of the Contempt of Court Act 1981.

Mr Justice Michael Humphreys ruled ‘these serving police officers were able to provide an account of events which purported to descend into the detail both of the attack on the Ulster Defence Regiment (‘UDR’) soldier and the planned counter terrorist operation. The material was considered worthy of inclusion in an academic thesis the subject matter of which was counter insurgency in Tyrone.’

The judge observed the public policy behind section 10 of the 1981 CCA is to encourage freedom of the press and promote the right of freedom of expression in Article 10 ECHR.

However, the judge ruled: ‘The same public interest does not arise in relation to academic writings such

as the one in question in this case, which is by its very nature private.’ The academic work is not addressed to the public at large or a section of the public- ‘On the contrary, it is expressly embargoed from publication until 2066.’

An article by Fiona McIntyre for Research Professional, a subscription news service for UK Higher Education, drew parallels with the case of Boston College in the United States- forced to hand over some interviews conducted for research purposes with those involved in the conflict after a huge court case that dragged on for years, despite promises of anonymity made to participants by researchers.

Update on law of Malicious Falsehood for Chapter 3

A rare Court of Appeal ruling on malicious falsehood in 2022 in the case of George v Cannell & Anor appears to have provided some flexibility in interpreting and applying the phrase ‘calculated to cause pecuniary damage.’

Lord Justice Warby supported the argument that a claimant need only prove that it was ‘inherently probable’ that the complained of statements would cause financial loss, rather than having to prove that they probably had caused such loss.

He extracted from case law the view that the word “calculated” in S.3(1) [of the 1952 Defamation Act] does not mean “intended”, but “objectively likely.”

The court agreed this was a forward looking interpretation and further supported the contention an award for injury to feelings could be granted in circumstances where the Claimant was unable to establish actual financial loss.

The ruling prompted Tony Jaffa in the Hold The Front Page Law Column to ask the question: ‘Has the Court of Appeal made malicious falsehood the new libel?’

Lord Justice Warby said at paragraph 70: ‘ The remedy for those in the position of these defendants is to avoid conspiring to utter false, malicious, and financially damaging statements, or to settle the claim promptly if discovered to have done so. I am not persuaded that giving s.3 its natural meaning is likely to have a significant chilling effect on truthful and honest speech. Experience suggests that claims for malicious falsehood are relatively rare and that the main brakes upon them are the need to prove falsity and, in particular, malice. This is notoriously hard to plead (allegations of malice are frequently struck out at the interim stage) and to prove. There are safeguards against abuse, including the Jameel jurisdiction.’

It would appear that the Appeal Court judge’s view is that these nuanced changes are not going to open the floodgates and create a new frontier in media law.

Update on applicability of Reynolds responsible journlism defence/privilege to statutory Section 4 Public Interest defence in 2013 Defamation Act. Chapter Three.

Section 4(6) of the 2013 Defamation Act states: ‘The common law defence known as the Reynolds defence is abolished.’

But does it mean that journalists should ignore the ten criteria that for many years have been seen as a bedrock of ethical and professional obligations in ensuring the protection against wrongly damaging somebody’s reputation?

They founded the concept of the developing common law public interest defence.

Precedents twisted and turned on whether all should be satisfied for the defence, or it was a matter of each case on its merits and context.

What appears to be happening in libel cases where the statutory public interest defence is put forward is that High Court judges of first instance are evaluating the success or failure of the defence on whether key and relevant criteria from Lord Nicholls’ 10 Reynolds case criteria were complied with.

The Reynolds criteria became known as the responsible journalism defence. Indeed, this is how Lord Nicholls defined it four years after the Reynolds ruling in 1999.

In a ruling of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council- Bonnick v Morris in 2003 he said:

‘Stated shortly, the Reynolds privilege is concerned to provide a proper degree of protection for responsible journalism when reporting matters of public concern. Responsible journalism is the point at which a fair balance is held between freedom of expression on matters of public concern and the reputations of individuals. Maintenance of this standard is in the public interest and in the interests of those whose reputations are involved. It can be regarded as the price journalists pay in return for the privilege. If they are to have the benefit of the privilege journalists must exercise due professional skill and care.’

‘Depending on the circumstances, the matters to be taken into account include the following. The comments are illustrative only.

- The seriousness of the allegation. The more serious the charge, the more the public is misinformed and the individual harmed, if the allegation is not true.

- The nature of the information, and the extent to which the subject-matter is a matter of public concern.

- The source of the information. Some informants have no direct knowledge of the events. Some have their own axes to grind, or are being paid for their stories.

- The steps taken to verify the information.

- The status of the information. The allegation may have already been the subject of an investigation which commands respect.

- The urgency of the matter. News is often a perishable commodity.

- Whether comment was sought from the plaintiff. He may have information others do not possess or have not disclosed. An approach to the plaintiff will not always be necessary.

- Whether the article contained the gist of the plaintiff’s side of the story.

- The tone of the article. A newspaper can raise queries or call for an investigation. It need not adopt allegations as statements of fact.

- The circumstances of the publication, including the timing.’

Lord Nicholls added: ‘This list is not exhaustive. The weight to be given to these and any other relevant factors will vary from case to case.’

In the end, can it not be argued that operation of the statutory public interest defence is not that different from the old and ‘abolished’ common law defence?

Looking at the statutory 2013 Defamation Act defence media defendants need to be under no illusions that unlike their compatriots in the USA, the onus is on them to defend and indeed prove this defence on the balance of probabilities.

The statutory defence offers the rubric that the media defendant is entitled to it if they ‘reasonably believed that publishing the statement complained of was in the public interest.’

Under Section 4(3) criterion 4 of Reynolds is negated when the court may ‘disregard any omission of the defendant to take steps to verify the truth of the imputation conveyed by it.’ But this only applies where the publication ‘was, or formed part of, an accurate and impartial account of a dispute to which the claimant was a party.’

Notice the qualifications- the report needs to be ‘an accurate and impartial account of a dispute.’

When judging whether the media defendant had a reasonable belief the publication was in the public interest, a ‘court must make such allowance for editorial judgement as it considers appropriate.’

And the defene is available ‘irrespective of whether the statement complained of is a statement of fact or a statement of opinion.’

Recent case law points to Judges regularly applying Reynolds’ criterion 7- ‘Whether comment was sought from the plaintiff [claimant]. He may have information others do not possess or have not disclosed.’

It is known as the right to reply. It is very much there is some professional journalist codes.

Mr Justice Nicklin in a 2021 ruling between the newspapers The Independent, i, and the Evening Standard and Bruno Lachaux said the newspapers should have verified the allegations because of their seriousness. And he criticised the failure to contact the claimant for comment, and to include his response in the articles.

Here are some of the key passages:-

Paragraph 173. ‘As a result of the failure to carry out any verification and the failure to contact the Claimant, the Independent Article did not contain anything by way of rebuttal from the Claimant or include his version of events. That was a serious failure in basic journalist good practice and a breach of the Defendants’ Code. This was not a case in which it could be concluded that the Claimant could have nothing valuable to contribute by way of response or answer. The only justification advanced for not contacting the Claimant was that he was not the (main) subject of the article. The Claimant was plainly a subject of the article and, in terms of likely reputational harm, likely to be the main casualty from its publication. Leaving aside the instruction in the Defendants’ Code that it was important “to abide not only by the letter but also [its] spirit”, the terms of the article squarely engaged the obligation to put the story to the Claimant. Beyond the argument that the Claimant was not the subject of the article, none of the First Defendants’ witnesses suggested that there was any other justification for not complying with this “good journalistic practice.”’

Paragraph 177. ‘The fact that the Claimant was libelled by the Independent Article was not a product of a carefully reasoned editorial judgment; it was a mistake, as was the failure to approach him for comment. Those involved in the original decision to publish simply failed to recognise the Claimant as someone who was likely to suffer serious reputational damage as a result of publication of the Independent Article. Even allowing for hindsight bias, this is not a borderline case. The First Defendant has failed to demonstrate that a belief that publication of the Independent Article was in the public interest was reasonable. The First Defendant’s s.4 defence in respect of the original publication of the Independent Article fails on this ground as well.’

The judge had explained in his analysis of the law that ‘providing they are not treated as any sort of ‘checklist’, the Reynolds factors will remain potentially relevant when assessing whether a defendant’s belief that publication was in the public interest was objectively reasonable.’

Mr Justice Nicklin relied on the speech of Lord Wilson in the Serafin v Makievizc case of 2020:

‘“In [Flood -v- Times Newspapers Ltd [2012] 2 AC 273] …, the defendant published an article taken to mean that there were reasonable grounds to suspect that the claimant, a police officer, had corruptly taken bribes. The allegation was false. This court held that the defendant nevertheless had a valid defence of public interest. Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers, the President of the court, said at [26] that in that case analysis of the defence required particular reference to two questions, namely public interest and verification; at [27] that it was misleading to describe the defence as privilege; at [78], building on what Lord Hoffmann had said in the Jameel case at [62], that the defence normally arose only if the publisher had taken reasonable steps to satisfy himself that the allegation was true; and at [79] that verification involved both a subjective and an objective element in that the journalist had to believe in the truth of the allegation but it also had to be reasonable for him to have held the belief. Lord Brown at [113] chose to encapsulate the defence in a single question. “Could”, he asked, “whoever published the defamation, given whatever they knew (and did not know) and whatever they had done (and had not done) to guard so far as possible against the publication of untrue defamatory material, properly have considered the publication in question to be in the public interest?”. Lord Mance at [137], echoing what Lord Nicholls had said in the Reynolds case at p.205, stressed the importance of giving respect, within reason, to editorial judgement in relation not only to the steps to be taken by way of verification prior to publication but also to what it would be in the public interest to publish; and at [138] Lord Mance explained that the public interest defence had been developed under the influence of the principles laid down in the European Court of Human Rights.”

It is also significant that Mr Justice Nicklin recognised how Lord Wilson extracted from the guidance and wording of the 2013 Defamation Act legislation the observation that: ‘the Explanatory Notes to the Defamation Act 2013 stated that the intention behind s.4 was to: “reflect the common law as recently set out in the Flood case and in particular the subjective and objective elements of the requirement now both contained in subsection 1(b).”’

This is a key factor about the statutory public interest defence. It needs to reflect the latest common law established prior to its enactment. This must be the discussion of the Reynolds criteria/privilege/responsible journalism defence in the Flood v Times UKSC ruling of 2012.

This ruling has been carefully analysed by Tony Jaffa in ‘Law Column: Bruno Lachaux and the Public Interest defence’ for Hold The Front Page.

Update Chapter Two

Introduction and development of live televising of Crown Court sentencing in England and Wales

Pages 39 to 42 of Chapter 1 of the printed book has a section on broadcasting and online coverage of the courts and following the inauguration of televising sentencing in the Crown Court for the first time at the Old Bailey 28th July 2022, the practice has been gathering what might be described as ‘gradual momentum.’

The head of law at ITV news, John Battle, who is also chair of the UK Media Lawyers’ Association has been given credit for successfully campaigning for this development over many years.

The guidance on who can and how to apply to televise sentencing is set out at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/broadcasting-crown-court-sentencing

Authorised media organisations approved for broadcasting the sentencing are the BBC, ITN, Sky and PA Media.

Any one of them needs to apply to the trial judge 5 days in advance of the sentencing hearing.

No one else can film, broadcast or take photos of any hearing at any time. These ‘authorised media’ can make their footage, including photographic stills from the filming available to other media publishers.

The judge makes a provisional decision at least 2 days before the hearing, and a final decision on the day of the hearing and all this decision making happens outside the courtroom.

The prosecution, defence, victim or his/her relatives cannot make representations and there is no right of appeal against the judge’s decision.

The sentencing judge decides whether sentencing can be broadcast live or not and will take into account any reporting restrictions that are in place.

If reporting restrictions do cover some of the content of a sentencing, ‘there will be a short delay before broadcast to comply with reporting restrictions’ and it is recognised ‘authorised media may need to edit footage before it’s broadcast.’

The copyright in the footage is retained by The Ministry of Justice, but the MOJ is not responsible for maintaining and transmitting the recordings on media platforms such as YouTube.

Key rules that have to be complied with:

1.Only the judge and their sentencing remarks can be filmed. Authorised media cannot film any other court user – including defendants, victims, witnesses, jurors and court staff.

2.Apart from those authorised media organisations identified (BBC, ITN, Sky and PA Media) and approved of by the Lord Chancellor ‘No one else can film, broadcast or take photos of any hearing at any time.’

How HMCTS and the Ministry of Justice explained this historic development for the Crown Court System in England and Wales. ‘Broadcasting from the Crown Court’ See: https://insidehmcts.blog.gov.uk/2022/08/19/broadcasting-from-the-crown-court/

Sky’s hosting platform of Crown Court Sentencing. See: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCF3HqeLrCkZgARQfyqj1m-g

Examples of televised sentencing since July 2022:-

Man jailed for life in first TV court sentencing (From the number One Court of the Central Criminal Court)

Woman jailed for 34 years for murdering and decapitating friend (Central Criminal Court)

Mother and boyfriend jailed for life over killing of teenage son (Leeds Combined Court Centre)

Reservoir Dogs attacker gets further 15 years for murdering partner (Bristol Crown Court)

Necrophiliac killer gets further four years for abusing dead women. 9th December 2022 at the Central Criminal Court, London also known as the Old Bailey.

Judge sentences Anne Sacoolas over Harry Dunn death. 9th December 2022 at the Central Criminal Court, London, also known as the Old Bailey.

Serial offender gets 38 year minimum jail term for brutal murder of Zara Aleena 9 Dec 2022 Central Criminal Court

Double jeopardy killer gets 25 years for 1975 rape and murder of teenage victim. 13th January 2023 at Huntingdom Law Courts.

Appeal Court- Criminal Division Sentence increased for rickshaw death crash driver. 25th January 2023

Pair jailed for 35 years for £4.6m murder and fraud plot. 1st February 2023, Central Criminal Court.

Serial rapist and ex-Met officer David Carrick jailed for at least 30 years 14 Feb 2023 Southwark Crown Court

Son gets life sentence for fatal attack on mother 14 Feb 2023 Central Criminal Court

Embassy spy who sold secrets to Russians jailed for more than 13 years 17 Feb 2023 Central Criminal Court

Parents jailed for manslaughter after disabled teen’s death, 2nd March 2023 Old Crown Court.

Wayne Couzens gets 19 months for indecent exposure in months before Sarah Everard killing, 6th March 2023 at the Central Criminal Court.

Woman, 22, jailed for eight-and-a-half years for false abuse and grooming gang claims, 14th March 2023, Preston Combined Court Centre.

Gunman who shot dead Olivia Pratt-Korbel, 9, jailed for at least 42 years. 4 Apr 2023 MANCHESTER CROWN COURT (CROWN SQUARE)

Mum and stepdad jailed over fatal attack on two-year-old daughter. Mr Justice Griffiths at Swansea Crown Court 26th April 2023.

Nigerian politician, wife and medic jailed over organ harvesting plot. Mr Justice Johnson 9th May 2023 at the Central Criminal Court.

Knifeman, 17, detained for murder of ‘defenceless’ 14-year-old. First televisied sentencing of a serious juvenile offender in the adult courts where anonymity reporting restrictions have been lifted. Judge Sarah Munro KC 10th May 2023 at the Central Criminal Court.

Teenagers get life for killing boy, 16, in mistaken identity attack. Judge Sarah Munro KC at the Central Criminal Court again on the same day (10th May 2023) at the Central Criminal Court. A reflection of the terrible toll of knife crime murders taking place in London with young people, often from Black and Asian ethnic communities being the victims.

Double killer gets third life sentence for sexually abusing boy. The Recorder of Nottingham, Judge Nirmal Shant KC at Nottingham Crown Court 11 May 2023. A double killer who brutally murdered two women in the 1990s was handed a third life sentence for violently sexually abusing a young boy in the years before his fatal attacks.

Killer of Nikki Allan, 7, jailed for at least 29 years three decades on. Mrs Justice Lambert at Newcastle Quayside Law Courts 24 May 2023. David Boyd, now 55, was convicted of the 1992 murder of schoolgirl Nikki Allan after advances in DNA technology allowed police to link him to the crime.

Parents jailed for life over murder of 10-month-old Finley Boden. Mrs Justice Tipples at Derby Combined Court Centre 27 May 2023. A couple who murdered their 10-month-old son on Christmas Day 2020 just weeks after he was returned to their care were both jailed for life. Shannon Marsden, 22, and Stephen Boden, 30, burnt and beat Finley Boden, leaving him with 130 separate injuries, including multiple bone breaks and fractures.

Mother and partner jailed for toddler’s violent death. A mother and her partner were jailed over the death of her 15-month-old son, who was shaken and beaten to death. 28 May 2023 Central Criminal Court before Mr Justice Sweeting.

Life sentence for teen terrorist who plotted attack on police and soldiers. The Recorder of London, Judge Mark Lucraft KC at the Central Criminal Court 2nd June 2023. A teenager who admitted he was planning a terror attack on the police and military was jailed for at least six years.

Killer, 15, gets 12-year minimum term for knife murder. 15 Jun 2023 Newcastle Quayside Law Courts before Mr Justice Martin Spencer. A 15-year-old boy was locked up for at least 12 years for stabbing another teenager to death.

Musician jailed for 15 years for killing student in “Mafia stiletto” stabbing. The Recorder of Manchester, Judge Nicholas Dean KC at Manchester Crown Court 19th June 2023. A musician who stabbed a student to death with a 13-inch ‘mafia stiletto’ knife after a comment over a skateboard was jailed for 15 years.

Government’s Rwanda asylum plan is unlawful, Court of Appeal rules. 29 June Royal Courts of Justice. Lord Burnett, the Lord Chief Justice, Master of the Rolls Sir Geoffrey Vos and Lord Justice Underhill.

Gunman who killed Elle Edwards in Christmas Eve pub shooting jailed for at least 48 years. Mr Justice Goose 8 Jul 2023 at Liverpool Crown Court. A gunman who shot dead a 26-year-old beautician when he opened fire on a packed pub on Christmas Eve was jailed for a minimum of 48 years.

People smuggler jailed for more than 12 years over Essex lorry deaths. Mr Justice Garnham 14 Jul 2023 at the Central Criminal Court. A people smuggler was jailed for more than 12 years for the manslaughter of 39 migrants who were found dead in a lorry trailer in Essex in 2019.

Teens sentenced to total of 34 years for mistaken identity knife murder. Mr Justice Choudhury at Wolverhampton Crown Court 14 Jul 2023. Two teenagers were jailed for a total of at least 34 years for the murder of 16-year-old in a mistaken identity attack. Pradjeet Veadhasa and Sukhman Shergill, both 17, stabbed Ronan Kanda to death close to his family home in Wolverhampton in June 2022.

Whole life term for killer who shot police officer Matt Ratana. Mr Justice Johnson at Norhtampton Combined Corwn and County Courts. 27 July 2023. A gun fanatic who shot dead a Metropolitan Police custody sergeant after smuggling a gun into a holding cell was handed a whole life jail sentence. Louis De Zoysa, 26, opened fire on Matt Ratana without warning using a legally-bought antique revolver and homemade bullets, causing a fatal wound to his heart and lung. Sgt Ratana, 54, later died in hospital.

Rape conviction quashed for man who spent 17 years in jail. 28th July 2023 at the Royal Courts of Justice London. Lord Justice Holroyde with Mr Justice Goose and Sir Robin Spencer. A man who served 17 years in prison had his rape conviction overturned after fresh DNA evidence emerged linking another suspect to the crime. Andrew Malkinson, now 57, was jailed for life with a minimum term of seven years in 2004 after he was found guilty of the attack on a woman in Salford, Greater Manchester – but he stayed in jail for another decade because he maintained his innocence.

Operators fined £14m over Croydon tram disaster failings. Mr Justice Fraser at the Central Criminal Court, 28th July 2023. Tram operators were fined a total of £14m after seven people were killed when a tram crashed in Croydon, south London. Transport for London was fined £10m and Tram Operations Limited was fined £4m for failing in their health and safety duties.

Stepfather and mother jailed over brutal death of baby Jacob Crouch. Mr Justice Kerr at Derby Combined Court Centre 4th August 2023. Craig Crouch, 39, was convicted of murder over a final, fatal attack on the child at his home in Linton, Derbyshire, in December 2020 and jailed for at least 28 years. His partner and Jacob’s mother Gemma Barton, 33, was cleared of murder and manslaughter but found guilty of causing or allowing the infant’s death following a trial at Derby Crown Court. Barton received a total sentence of 10 years.

Killer nurse Lucy Letby gets 14 whole-life sentences. Mr Justice Goss at Manchester Crown Court 21st August 2023. Serial killer nurse Lucy Letby will never be released from prison after she was given 14 whole-life orders for murdering seven babies and attempting to murder six others. The former neonatal nurse, 33, fatally injected seven infants with air, tried to kill two others by lacing their feeding bags with insulin and attempted to force a tube down another’s throat.

An example of a ruling from the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) in July 2022 when the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales presented judgement in linked appeals concerning the issue of ‘whole life terms.’ The appellants included Metropolitan Police officer Wayne Couzens convicted of the murder of Sarah Everard.

What is the current law in respect of broadcasting the courts in England and Wales?

The new edition of the Judicial College Guidelines on reporting restrictions in the Crown Court (2022) sets this out under section 5(7) at pages 45 and 46:-

Live-streaming, broadcast and electronic transmission of court proceedings

The statutory prohibitions on the recording and transmission of court proceedings do not apply to the transmission of video and audio of court hearings into a second courtroom, or to another location in England and Wales which is designated as an extension of the court. Not infrequently in criminal proceedings which attract a high level of public and press interest a second courtroom will be made available to permit a greater number of people to follow the proceedings in this way.

Until 2022, however, the general rule was that the statutory prohibitions on taking and publishing photographic images and sound recordings of court proceedings meant that courts had no power to allow their proceedings to be electronically transmitted to the general public. Any exception to this general prohibition requires further legislation.

There are four exceptions where Parliament has intervened to permit the live-streaming or electronic transmission of court proceedings.

- First, s.47 Constitutional Reform Act 2005 creates an exception to the general rule for proceedings in the Supreme Court, which are broadcast online on the Supreme Court Live service.209

- Secondly, the Crime and Courts Act 2013 s.32 empowers the Lord Chancellor to make regulations disapplying the prohibitions on making sound recordings and photographic images, thereby permitting the live-streaming of court proceedings. To date, orders have been made permitting the live-streaming of:

- Public hearings before the full court of the Court of Appeal.

- Sentencing remarks of certain specified judges in the Crown Court, with the permission of

the relevant judge. - Thirdly, the Coronavirus Act 2020 made temporary amendments to the Courts Act 2003, in light of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, to enable certain criminal proceedings to be conducted by means of video or audio link and to permit the ‘broadcast’ of criminal proceedings conducted wholly by means of video or audio, for the purpose of enabling members of the public to see and hear the proceedings. As this power was limited to proceedings conducted ‘wholly’ by video or audio link, it follows that it did not confer power to permit live-streaming of criminal court proceedings which took place in person, or partly in person. This power did not allow a court conducting a fully remote hearing to permit a TV production company to record and then re-broadcast the proceedings.214

- Fourthly, the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 replaces the temporary powers under the Coronavirus Act with permanent amendments to the CJA 1925, CCA 1981 and the Courts Act 2003. These allow the Lord Chancellor to empower the Court to direct the electronic transmission of images or sounds of proceedings of all kinds for the purpose of enabling persons not taking part in the proceedings to watch or listen to them, though onward recording and broadcasting is prohibited.

On 28th July 2023 ITN’s head of legal and compliance John Battle wrote an article for Press Gazette on how the success of filming in UK courtrooms is restoring trust in justice: ‘Cameras in courts one year on: An unqualified success.’ See: https://pressgazette.co.uk/comment-analysis/cameras-in-courts-one-year-on-an-unqualified-success/

There is now an extensive infrastructure of televised broadcasting of Appeal Court Civil Division cases from the Royal Courts of Justice with streaming on YouTube though permission is not given for the material to be broadcast and re-used by the media:

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 63

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 70

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 71

Court of Appeal Civil Division – Court 73

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 74

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 75

Court of Appeal – Civil Division – Court 76

Two judges whose sentencing has featured in live televised hearings in the past year, His Honour Judge Mark Lucraft, the Recorder of London, and Mrs Justice Cheema Grubb, have offered their views on the project in a Ministry of Justice media release: ‘One year of broadcasting of sentencing remarks in the Crown Court.’

See: https://www.judiciary.uk/one-year-of-broadcasting-of-sentencing-remarks-in-the-crown-court/

Legal journalist Joshua Rozenberg KC has also written an excellent analysis and review of one year of televising the sentencing in English courts for Law Society Gazette: ‘Letting the public see how the public law works.’ (pages 12 to 13)

The outgoing Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales Lord Burnett has also been making his views on Open Justice and televising the courts in a speech to the Commonwealth Magistrates’ and Judges’ Association in Cardiff in September 2023.

He said: “The question when considering the live-streaming or broadcasting of additional types of case or parts of cases, in my view, should be: why not?”

He supported the common law tradition of Open Justice in identifying judges and parties and resisting anonymization which is the practice in civil and Roman law jurisdictions.

He observed the European Court of Human Rights had not named the duty judge who temporarily prevented the UK from sending asylum-seekers to Rwanda last summer — “something that is alien to the common law tradition.”

See: London Evening Standard 12th September 2023 ‘Strong argument to go further with cameras in courts, says Lord Chief Justice. Lord Burnett said the broadcasting of sentencing in some criminal cases had been ‘successful beyond our expectations’.

Also reported in Standard’s sister online national publication The Independent.

Ministry of Justice Open Justice Consultation 2023

In May 2023, the Ministry of Justice opened a consultation on Open Justice. See: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/open-justice-the-way-forward/call-for-evidence-document-open-justice-the-way-forward

A research document ‘Open Justice: the way forward Call for Evidence’ was released 10th May at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1155744/open-justice-cfe.pdf

Ministry of Justice Open Justice Consultation 2023

In May 2023, the Ministry of Justice opened a consultation on Open Justice. See: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/open-justice-the-way-forward/call-for-evidence-document-open-justice-the-way-forward

A research document ‘Open Justice: the way forward Call for Evidence’ was released 10th May at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1155744/open-justice-cfe.pdf

The call for evidence ends 7th September 2023 and invites contributions on a wide range of topics: Open Justice; listings; accessing courts and tribunals; remote observations and livestreaming; broadcasting; Single Justice Procedure; publication of judgments and sentencing remarks; access to court documents and information; data access and reuse; and public legal education.

See Law Society Gazette ‘Court photography ban under review in transparency drive’ at: https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/practice/court-photography-ban-under-review-in-transparency-drive/5116009.article

Media law pdf file briefing on this subject

Update to Chapter 10 Freedom of Information

Unsuccessful Judicial Review challenge of failure of FTT and UT Information Rights to apply ECtHR Grand Chamber ruling Magyar v Helsinki 2016

The ruling of Mr Justice Ritchie on 11th November 2022 is the end of the road for a longstanding attempt through multiple appeals to the First Tier Tribunal and Upper Tribunal (Information Rights) by Professor Tim Crook to persuade the UK domestic legal system to read down Article 10 Freedom of Expression rights against the statutory absolute exempltions in the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

This was in the context of the ECtHR Grand Chamber in Magyar v Helskini ruling in 2016 that public watchdog journalists, academic researchers, and NGOs had a qualifed standing right under Article 10 to state information.

Mr Justice Ritchie decided ‘There is no arguable error of law asserted, only an impassioned plea for the law in S.23 of the Freedom Of Information Act to be changed. Parliament changes the law, not the Courts.’

He rejected Professor Crook’s application for leave for judicial review and certified it as ‘totally without legal merit.’ This provision meant it would have been highly unlikely that further appeal attempts to the Appeal Court Civil Division and UK Supreme Court would have had any chance of success.

Professor Crook had mounted five First Tier Tribunal appeals and three Upper Tribunal applications for permission to appeal in striving to achieve recogntion of his public interest/watchdog right to information withheld from him by a state information monopoly.

In every case the tribunals insisted they were determined by Act of Parliament (creatures of FOIA) and the King’s Bench Division Administrative Court was not prepared to accommodate any judicial review seeking declaration of incompatilibity with Article 10 rights.

For lawyers, journalists, academics and law students interested in finding out more about the background to this case, please see Profesor Crook’s statement of facts, legal grounds and rememdies sought which were submitted in the application for judicial review. The full core bundle is not in the public domain because it contained some private information and documents covered by privacy/confidentiality issues. Relevant Upper Tribunal rulings and links to FTT rulings are provided below.

Please also find the three rulings by Upper Tribunal (Information Rights) Judges refusing permission to appeal against First Tier Tribunal rulings on appeals pursued by Professor Crook.

Judge Edward Jacobs Upper Tribunal ruling 20th April 2022 Crook v Met Police & ICO UA-2021-000143-GIA

Judge Rupert Jones Upper Tribunal Ruling Crook v ICO 13th September 2021 GlA 446 & 447/2021

Judge Stewart Wright Upper Tribunal Ruling 22nd July 2021 GlA/2103/2019 & GIA/753/2020